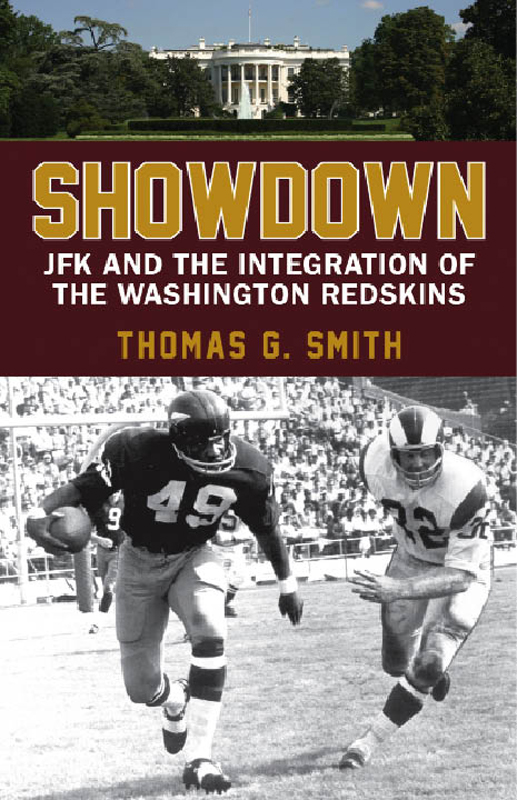

SHOWDOWN

JFK and the Integration of the Washington Redskins

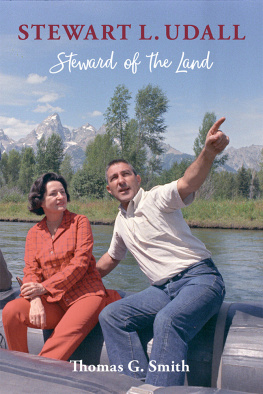

Thomas G. Smith

Beacon Press Boston

For Sandra

Contents

Prologue. Redskins Told: Integrate or Else

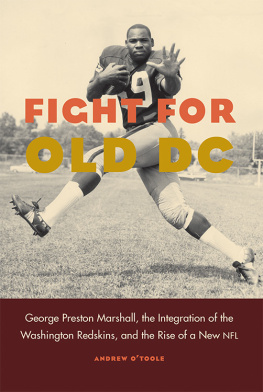

In 1961as America hummed with racial tensionthe Washington Redskins stood alone as the only team in professional football without a black player on its roster. In fact, in the entire twenty-five year history of the franchise, no African American had ever played for George Preston Marshall, the Redskins cantankerous principal owner. But that was about to change.

On March 24, 1961, Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall warned Marshall to hire a black player or face federal retribution. A crew-cutted, youthful, athletic Arizonan, Udall in many ways embodied the image of a vigorous, can-do New Frontiersman. As a three-term Democratic congressman in the 1950s, he had won respect as a hard-working legislator who supported liberal causes, including the preservation of the environment and civil rights. When named Interior secretary by John F. Kennedy, he seized the opportunity to promote racial equality by pressuring the Washington Paleskins, as he called them, because he considered it outrageous that the Redskins were the last team in the NFL to have a lily-white policy.

If Marshall did not integrate his team, threatened Udall, then the government would withhold the use of the Redskins home playing field, D.C. Stadiuma publicly financed and newly built 56,000-seat arena located on public terrain at Anacostia Flats. Marshall had recently signed a thirty-year lease to play all home games at D.C. Stadium, and as the landlord of the parks system, the Interior Department could deny use of the stadium to any entity practicing discriminatory hiring policies.

Realizing that racial justice and gridiron success had the potential to dovetail or take an ugly turn, civil rights advocates and sports fans alike anxiously turned their eyes toward the nations capital. There was always the possibility that Marshallone of the NFLs most influential and dominating pioneersmight defy such demands from the Kennedy administration to desegregate his all-white team. With slicked-down white hair and angular facial features, the nattily attired, sixty-four-year-old owner presented a formidable visage in 1961. He had a well-deserved reputation for flamboyance, showmanship, and mercurial behavior. And, like other Southern segregationists, Marshall stood firm against race mixing. Well start signing Negroes, he once boasted, when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.

With its abysmal record of 1 win, 12 losses, and 1 tie the previous season, the Redskins had a real opportunity to improve themselves by making a competent selection. The player draft rules for the fledging American Football League (AFL) and the older National Football League (NFL) were the same: teams would draft or select players in inverse order of their won-lost records. In other words, teams with poor winning percentages, like the Redskins, would be given an opportunity to select talented college players before teams with higher winning percentages. The AFLs Oakland Raiders had first pick in 1961, with the NFLs Redskins to follow two days later.

As the two stubborn and strong-willed titans, Udall and Marshall, clashed over federal desegregation efforts, Americans waited in great anticipation for the start of the December 1961 draft. Washington could draft Ernie Davis, a powerful Syracuse University running back who had become the first African American to win the Heisman Trophy. Drafting Davis might mean later losing him to the rival AFL for more money. The team could select Davis and trade him for two or three less-talented white or black players; or it could bypass Davis entirely to select a white player. It seemed unlikely that Marshall would defy the government and renege on his agreement to hire black players, but he was difficult to intimidate and unpredictable to boot. No one, including a well-intentioned presidential cabinet member, he said, could tell him who to hire for his private business. With the possibility of noncompliance in mind, on December 1, Udall issued a final warning to Marshall to honor his pledge to desegregate the team. The draft, he said, is the showdown on this.

Chapter 1. Boston Beginnings

The Redskins professional football team was founded in New England by a bigoted Southerner. Lean and loquacious, brash and uninhibited, George Preston Marshall wore his black hair slicked back and parted down the middle. Dressed in a Bond Street suit and tie, with a gold-headed walking stick, he cut an imposing figure and was often identified in the press as Marshall the Magnificent, George the Gorgeous, or the well-dressed man. The sports writers have had a lot of fun with Showman Marshall, he once wrote. Ive enjoyed every word of it. As a leading sportsman, he could be seen in choice seats at the ballpark, racetrack, or boxing arena.

Marshall was born in 1896 in Grafton, a West Virginia railroad and coal-mining town of 5,200 people (160 of whom were black) where his father, T. Hill Marshall, published a newspaper, the Grafton Leader. George grew up in the racially segregated South and likely had no black acquaintances. While he never learned racial tolerance, he did learn about the power of marketing. At age nine, when he had trouble selling a female rabbit for 25 cents, he advertised it in his fathers newspaper as a rare Jacksonville hare. Both the buyer and a couple of would-be buyers attracted by my ad, he later wrote, inspected all points of my rabbit and learnedly agreed that she was a very fine specimen of Jacksonville hare indeed. He sold the rare hare for $1.25. That promotion led to others. Im guilty of having ideas and being a showman, he once said. My defense is that promotional ideas and showmanship have never done anybody any harm.

As a youth, he also displayed an interest in athletics, playing baseball and serving as a batboy during the 1909 season for the Grafton team in the PennsylvaniaWest Virginia Class-D minor league. The following year, at age fourteen, he organized a football team to compete against teams from adjoining towns, and donations from fans watching those contests sometimes totaled more than $20 (the equivalent of more than $400 today). He attended schools in Virginia and, later, in Washington, D.C., where his father had opened a laundry business.

George attended the tenth grade at Central High, a segregated public school in Washington, and the eleventh grade at the privately run Friends Select School. Established in 1883 by Thomas Sidwell, the nonsectarian school was located four blocks from the White House. Emphasizing Christian values, the school began with 28 pupils and grew to more than 200 when Marshall attended from 191314. The school accepted girls from its beginnings, but it did not enroll its first African American student until 1956, two years after the U.S. Supreme Court mandated the desegregation of public schools in the Brown decision. Eventually, the private school morphed into a college preparatory school (now the Sidwell Friends School) emphasizing academic excellence, community service, earth stewardship, and racial, religious, and economic diversity. Bobby Mitchell, the first black player for the Redskins, enrolled his two children in the school in the late 1970s, and in 2009, President and First Lady Obama sent their children there.

At the Friends Select School, Marshall played baseball and also developed a passion for dramatic acting. His love for the stage prompted him to quit school at age eighteen to join an acting company. The closest he came to expressing misgivings about this failing came in a letter recalling the nurturing influence of the Sidwells. The only real regret I have ever had in my life, he wrote in 1934, was I did not spend more time with Mrs. Sidwell and yourself in my youth.