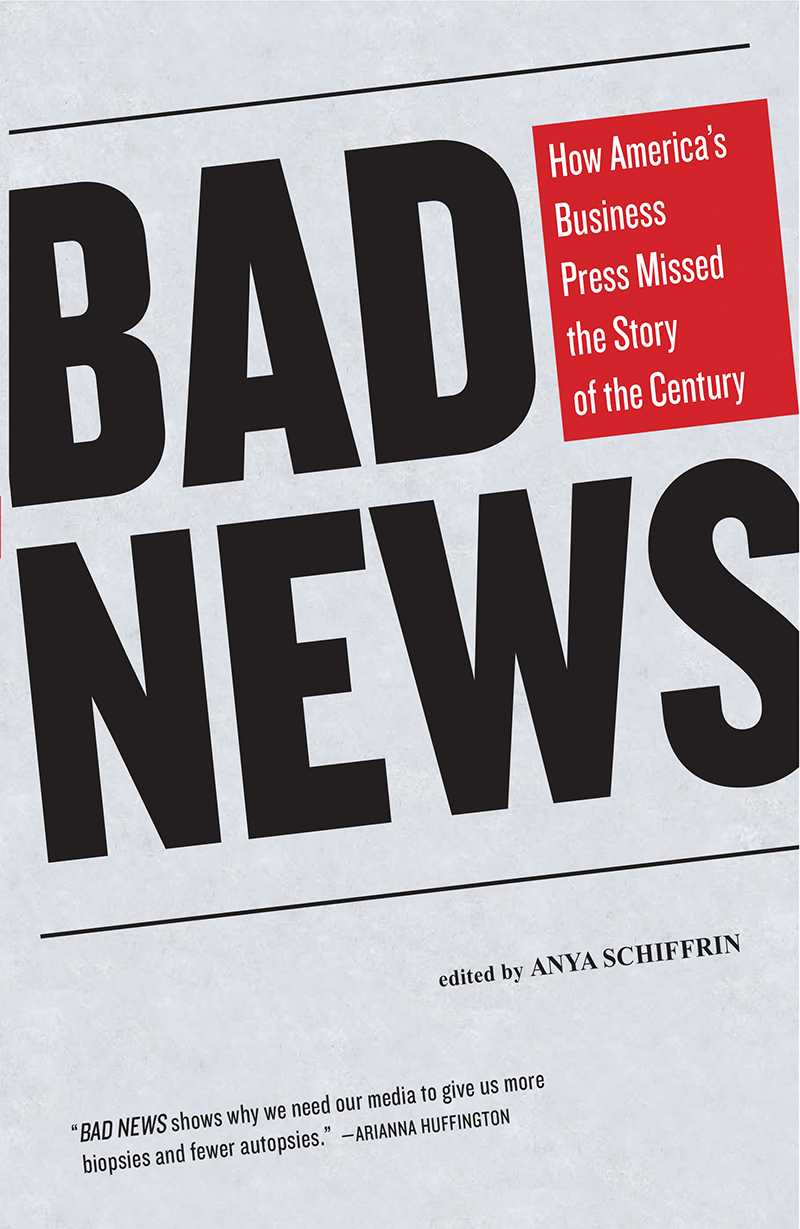

BAD NEWS

HOW AMERICAS BUSINESS PRESS MISSED THE STORY OF THE CENTURY

EDITED BY

ANYA SCHIFFRIN

THE NEW PRESS

NEW YORK LONDON

Individual chapters 2011 by each author

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to:

Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York, NY 10013.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2011

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bad news : how Americas business press missed the story of the century / edited by

Anya Schiffrin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59558-549-3 (hc)

1. Journalism, Commercial--United States. 2. Financial crises--United States. 3. United States--Economic conditions--2001-2009. I. Schiffrin, Anya, 1962

PN4784.C7B33 2010

070.4--dc22

2010035640

The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by The Influx House

This book was set in Janson Text

For Andr and Leina

PREFACE

Anya Schiffrin

T he roots of this book begin for me in Hanoi in the late 1990s.I was there for the first two years of the Asian financial crisis, and it was interesting to report in a place where the media were controlled by the Communist Party and government. Banking was an important part of my beat and, like other countries in Asia, Vietnam was in the middle of a banking crisis with a number of state-owned banks that were saddled by large amounts of nonperforming loans. The government was so afraid of bank runs and loss of confidence that the Politburo passed a law early in 1997 making nonperforming loans a state secret. We worked in an atmosphere of secrecy, and it made getting information difficult and meant that Vietnamese reporters were unable to report on much of what they found out.

When the U.S. financial crisis started, I saw some points in common. There was the fear of undermining confidence by printing bad news accompanied by pressure from government and, in some cases, readers not to do so. There was a collapse in advertising revenueswhich preceded the crisis but was aggravated by the economic downturn. There were the ensuing layoffs and staff cuts that made journalists fear for their jobs and perhaps more afraid to stand out from the rest of the pack.

At the same time, new opportunities opened up: if you are a business journalist, you toil away doing routine earnings and stock market stories that are buried on the back pages. But during a crisis everyone is interested in business and the economy. For those journalists, there is also the chance to write stories that are usually shunted asidedetailed explanations of different financial instruments and the chance to write about how real people are affected. We began to see all kinds of reporting that we would not normally see in the business pages.

These were the impressions I had, and when we began doing research on the effects that economic crises have on the media, I found there was very little written on the subject. What is available are a lot of articles written by journalists and media critics after bubbles burst. Both the dot-com collapse of the late 1990s and the demise of energy giant Enron ushered in a period of soul-searching and questioning about why the crisis was not predicted earlier.

I wanted to produce a book that would look not just at the mistakes the press made in the run-up to the crisis, but also at the coverage that took place during the crisis. I wanted to highlight some of the good reporting that emerged as well as some of the omissions and hopefully unearth some suggestions for how business and economic reporting could be improved in the future.

This book covers all of those topics. The first two chapters, by me and Joseph E. Stiglitz, give an analytical framework for understanding business journalism. Ive drawn on the academic research in the field, and Stiglitz has applied some of his theories of asymmetric information to the coverage weve seen. Dean Starkman looks into the press coverage leading up to the crisis and examines why it was so weak in many cases. Ryan Chittum investigates the coverage during the crisis while Moe Tkacik analyzes the way television in the modern era contributed to the bubble. Peter S. Goodman talks about his experiences trying to bring in the stories of real people to his beat and how he used their (often very sad) experiences to supplement the macroeconomic reporting he did at the New York Times . Chris Roush defends the business press and puts much of the criticism into historical context. Stephen Schifferes describes the experiences he had working for the BBC. And we finish with Bob Giles and Barry Sussman from the Nieman Watchdog Project who describe to us what good coverage can look like.

The role of the press during this past crisis is likely to be studied for years to come and taught in our universities and journalism programs. I hope this book will add to the discussion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge the Roosevelt Institute in New York and Andrew Rich for supporting this book, as well as the April 6, 2010, conference at Columbia University from which this book originated.

1

THE U.S. PRESS AND THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

Anya Schiffrin

T he financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 came at a time when American journalism was already imploding. Beset by job losses and the migration of advertising revenue to the Internet, traditional media was in a decline that seemed irreversible. Major newspapers like the Los Angeles Times , Chicago Tribune , and the New York Times cut jobs and offered buyouts to many of their staffers.

As almost everyone knows, the economic foundation of the nations newspapers, long supported by advertising, is collapsing, and newspapers themselves, which have been the countrys chief source of independent reporting, are shrinkingliterally, wrote Leonard Downie Jr. and Michael Schudson in their report, The Reconstruction of American Journalism, published on the Columbia Journalism Review Web site in October 2009. Overall, according to various studies, the number of newspaper editorial employees, which had grown from about 40,000 in 1971 to more than 60,000 in 1992, had fallen back to around 40,000 in 2009.

The problems that beset the industry took a toll on the reporting that took place during the crisis. Afraid for their jobs and struggling with fast-moving and complicated events, reporters struggled to keep up with the most complicated story that many of them had ever coveredall the while worrying about their own futures. Sometimes reporters were even personally involved, suffering from financial troubles while covering the story. The most famous case was that of former New York Times writer Edmund L. Andrews, whose book Busted chronicled his own troubles keeping up with his mortgage payments even while he was covering the economy from Washington, DC.

Next page