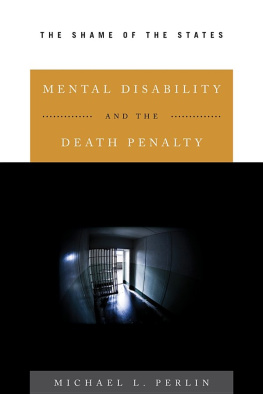

Intellectual Disability and the Death Penalty

Current Issues and Controversies

Marc J. Tass and John H. Blume

Copyright 2018 by Marc J. Tass and John H. Blume

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tass, Marc J., author. | Blume, John H., author.

Title: Intellectual disability and the death penalty : current issues and controversies / Marc J. Tass and John H. Blume.

Description: Santa Barbara, California : Praeger, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017037271 (print) | LCCN 2017045921 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440840159 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440840142 (hardcopy : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Capital punishmentUnited States. | Offenders with mental disabilitiesLegal status, laws, etc.United States. | People with mental disabilities and crimeUnited States. | Mentally illCommitment and detentionUnited States. | Insanity (Law)United States.

Classification: LCC KF9227.C2 (ebook) | LCC KF9227.C2 T37 2017 (print) | DDC 345.73/0773dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017037271

ISBN: 978-1-4408-4014-2 (print)

ISBN: 978-1-4408-4015-9 (ebook)

22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

Preface

In its 2002 landmark decision in Atkins v. Virginia , the Supreme Court of the United States held that the execution of people with intellectual disability was a cruel and unusual punishment barred by the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In doing so, the Court, implicitly and at times explicitly in its opinion, recognized the lesser culpability of this vulnerable population. While the Atkins Court gave states some latitude to develop appropriate mechanisms for assessing intellectual disability in capital cases and thus implementing the new constitutional exclusion against capital punishment for people determined to have intellectual disability, some jurisdictions have mistakenly interpreted Atkins as allowing them to deviate, in some instances markedly, from the generally recognized national professional consensus regarding the determination of intellectual disability. At bottom, intellectual disability remains a clinical diagnosis, and the states and their courts must recognize and apply existing nationally accepted clinical definitions to guide their decisions in determining whether the individual in any Atkins hearing has intellectual disability. This was reiterated in the most recent Supreme Court rulings in Hall v. Florida (2014) and Moore v. Texas (2017).

Determining whether a particular capital defendant or death row inmate has intellectual disability in many death penalty cases has been far from a simple clinical exercise. This is so for a number of reasons, including (1) resistance to the Supreme Courts decision in Atkins itself; (2) the use of scientifically unsound definitions of intellectual disability and assessment methods for its determination; (3) judge, juror, and attorney stereotypes of people who have an intellectual disability; (4) the use of expert witnesses who lack familiarity with and clinical judgment in intellectual disability; and (5) racial and ethnic bias. Despite being informed by more than a decade and a half of experience since the Courts decision in Atkins , many issues remain controversial and unsettled for judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, jurors, as well as mental health experts called upon to make determinations of intellectual disability in capital cases.

Drawing upon our different experiences as a psychologist who has worked for decades with people with intellectual disability and a legal academic who has devoted a significant amount of his career to studying the legal treatment of persons with a variety of mental impairments, this book reviews the major clinical and legal issues and controversies surrounding the matter of the death penalty in America when the defendant is suspected of having intellectual disability. We have attempted to do so as thoroughly and objectively as possible as we intend for this book to be a valuable resource for mental health experts, attorneys, investigators, mitigation specialists, and other members of legal teams, as well as judges who, willingly or unwillingly, become involved in an Atkins hearing and want to better understand the relevant issues at hand.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank ABC-CLIO/Praeger Publishers for the forethought and invitation to write this book. We also thank Debbie Carvalko, Senior Acquisitions Editor, Psychology and Health, at ABC-CLIO/Praeger Publishers, for her guidance and support throughout the process of bringing this book to fruition.

We extend our warmest gratitude to Wesley R. Barnhart, Kelsey L. Bush, Kristin DellArmo, Stoni L. Fortney, Dr. Susan M. Havercamp, Emily Paavola, and Lindsey Vann (alphabetical order) for reviewing and providing insightful comments on earlier drafts of the chapters contained in this book. We also wish to thank Monica A. Sandoval for her assistance with formatting of the chapters into APA publication style, and Charlie Sim and Jackie Newman for research assistance.

Marc Tass extends warm thanks to Professor Ruth Luckasson for her encouragement more than a decade ago to dive into the criminal justice issues associated with intellectual disability and to become involved in Atkins cases, it has been an intellectually stimulating journey to say the least. He also extends his warmest gratitude to his spouse and colleague, Dr. Susan M. Havercamp, who is the first peer reviewer he seeks input from and who is always patient and understanding.

John Blume would like to thank Professors Ruth Luckasson and Jim Ellis who first introduced him 30 years ago to the special challenges persons with intellectual disability face when charged with a capital crime or sentenced to death. He would also like to thank the clients with intellectual disability whom he has interacted with over the years for the lessons they have imparted. And, last but not least, he would like to thank his spouse, Drucy Glass, for her patience and support.

Marc J. Tass and John H. Blume

CHAPTER ONE

Intellectual Disability and How It Is Diagnosed

Intellectual disability is a multifaceted and complex condition that comes in a wide range of clinical presentations but has historically been defined by three long-standing criteria and/or prongs related to (1) significantly subaverage intellectual functioning, (2) significant subaverage adaptive behavior as expressed in conceptual skills (language, reading, and writing, and money, time, and number concepts), social skills (interpersonal skills, social responsibility, self-esteem, social problem solving, following rules and obeying laws, avoiding being victimized, and wariness), and practical skills (personal hygiene, safety, healthcare, travel/transportation, following schedule, home-living skills, and occupational skills), and (3) if the individuals impaired functioning originated during the developmental period (see American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013; Schalock et al., 2010). Although the developmental period is not operationally defined in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), the developmental period is generally considered to be from birth through the age of 18 years (Schalock et al., 2010). The causes or risk factors leading to impaired functioning typically associated with intellectual disability can originate prenatally (e.g., genetic or chromosomal factors, maternal alcohol or drug consumption during pregnancy, trauma or insult during fetal development, etc.), perinatally (e.g., anoxia, infection transmission, trauma, etc.), and/or postnatally (e.g., deprivation, brain injury, exposure to teratogens, etc.). Intellectual disability can be the result of any number of known genetic syndromes or risk factors. Establishing the exact etiology associated with intellectual disability is not needed to make a diagnosis. Knowing the cause or causes can be of value to the individual and/or his or her family, especially for the purposes of family planning and counseling.

Next page