Why Irrational Politics Appeals

Copyright 2017 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fitzduff, Mari, editor.

Title: Why irrational politics appeals : understanding the allure of Trump / Mari Fitzduff, editor.

Description: Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016042449| ISBN 9781440855146 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781440855153 (EISBN)

Subjects: LCSH: Trump, Donald, 1946Public opinion. | Presidents--United StatesElection2016. | Political cultureUnited States. | Personality and politicsUnited States. | United States--Politics and government2009

Classification: LCC E901.1.T78 W54 2017 | DDC 973.932092dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016042449

ISBN: 978-1-4408-5514-6

EISBN: 978-1-4408-5515-3

212019181712345

This book is also available as an eBook.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

Mari Fitzduff

Stephen Reicher and S. Alexander Haslam

Mark R. Leary

Micha Popper

Ronald E. Riggio

Michael C. Grillo

Gregg Henriques

Matthew C. MacWilliams

Florette Cohen, Sharlynn Thompson, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon

Karina V. Korostelina

J. P. Prims, Zachary J. Melton, and Matt Motyl

Mark Chou and Michael L. Ondaatje

Christopher S. Reina

Mari Fitzduff

Mari Fitzduff

Its a thing to behold, almost as if hed grabbed the slender wrists of the crowd with those big hands of his, felt for the pulse of their darkest hearts and then whispered the words they so long to hear. (Malone, 2016)

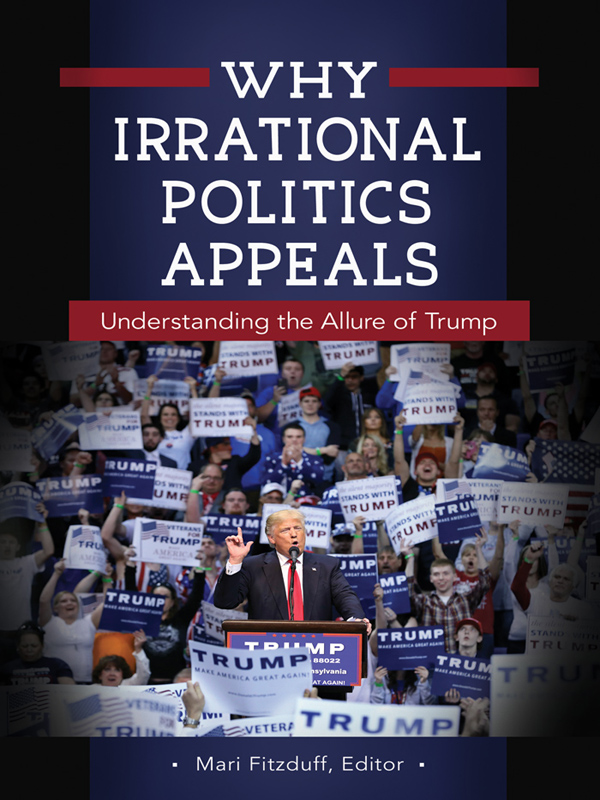

The idea for this book came about when it became apparent in the summer of 2016 that Donald Trumps campaign for the presidency had, against all odds, gained traction. The idea that such an apparently outrageous personality, without any governance experience or visible moral consistency, could become the Republican candidate was hard to believe. There was however reassurance from the polls and the pundits that this was as far as it could go: Trump could never become president. But, since the results poured in on the night of November 8, the commentators who had been so unanimous in their prediction of a Trump defeat began to rethink many of the assumptions that guided their beliefsnot just about presidential elections but also about the very fabric of democratic life in the United States.

The authors of the chapters in this book began that process a little earlier. In this collection we have brought together the finest minds in their respective fields to reflect on people who took the Trump phenomenon seriously from the outset, and who, as his campaign took off, used a variety of disciplines such as social and political psychology, neuroscience, and evolutionary and leadership/followership studies to analyze the processes by which apparent irrationality came to be viewed by a large slice of the American population as the rational choice.

We understand that there are many people who dismiss Trumps followers as irrational and ignorant and who will condemn them for their support of someone whom they see as fickle, ill-informed, vulgar, divisive, and with worrying autocratic tendencies. As noted by Reicher and Haslam (), It is far too easy and too common to dismiss those whose political positions we disagree with as fools or knavesor, more precisely, as fools led by knaves. However, by just reproaching and condemning such followership, we may miss, or avoid, understanding why their support for Trump makes sense for them, given the contexts in which they live, and our human predispositions that make their desire for a leader such as Trump explicable. If we fail to take the time to hear and understand them, we may fail to note the very serious questions that their support for Trump raises for our society and democracy in the years ahead.

Who Were Trumps Initial Followers?

Is Trumps success a product of his own creation? Or is it a product of the particular social context at this moment of time in U.S. and global history? The Trump phenomenon appears to have risen from an unusual convergence of an economic and social context that is unsettling for many people, political systems that seem to be permanently unproductive, and a desire for a different style of leadership and politics.

By the summer of 2016, a consensus had built among media commentators. Drawing upon polling evidence, they characterized Trumps core supporters as being male, white, and nominally Christian (Thompson, 2016). Trump entered the political leadership arena at a time when many of them were feeling economically and psychologically excluded from the promise of the American dream, that is, the opportunity for prosperity, success, and upward social mobility for their families and children. Their wages were an average of $72,000 per annum, which is just above the median wage of $56,000. For two decades, they have seen their wages stagnate or even decline in real terms (Stone et al., 2015). Relatively speaking, they are increasingly worse off, as most financial gains are now accruing to the top 1 percent of society (Boxer, 2016). They are progressively finding themselves unemployed because manufacturing has been outsourced as part of globalization, and because migrants are more willing to take up the poorly paid jobs that are available (Comen & Stebbins, 2016).

The coal industry, previously a major employer, is particularly in decline because of new energy policies. In June 2016, estimates showed that coal production was down across the country by 29 percent in the first 10 weeks of 2016 compared with the same period in 2015 (Goldenberg, 2016). The decline has not only resulted in growing and sustained poverty, but it has also significantly affected the mortality rate for middle-aged white people in the United States. A 2016 analysis notes that between 1999 and 2014, mortality rates in the United States rose for white Americans aged 22 and 56, while before that death rates had been falling by nearly 2 percent each year since 1968 (Case & Deaton, 2015). This decline has been attributed to less-educated workers increasing disengagement from the mainstream economy; declining levels of social connectedness; weakened communal institutions; and the splintering of society along class, geographic, and cultural lines (Khazan, 2016).

Trumps initial followers were 89 percent white. He appealed most strongly to those whites that hold negative views of African Americans. Thirty-three percent of Trump early voters agree with the statement blacks are less intelligent than whites, as opposed to 22 percent of other parties, and 40 percent of Trump supporters believe blacks are more lazy than whites, versus 26 percent of other parties (Reuters/Ipsos, 2016). Many of them also feel that too many current policies favor the rights of black and LGBT citizens more than they support the rights of poor whites, and these showed a disproportionately greater support for Trump during the primary elections (Tesler & Sides, 2016).