Alliance Rises in the West makes a significant contribution to the archaeology and history of labor, race, and the politics of alliance of industrial communities in the American West.

Donald L. Hardesty, author of Mining Archaeology in the American West: A View from the Silver State

Sunseris book makes a very important contribution to the field of historical archaeology in the West and offers a broad set of contributions to historical archaeology globally and to our understanding of intersubjectivity in the past. Sunseri masterfully sweeps research that is far ranging across the fields of ethnicity, race, class, and, most significantly, labor.

Carolyn L. White, editor of The Materiality of Individuality: Archaeological Studies of Individual Lives

Historical Archaeology of the American West

Series Editors

Annalies Corbin

Rebecca Allen

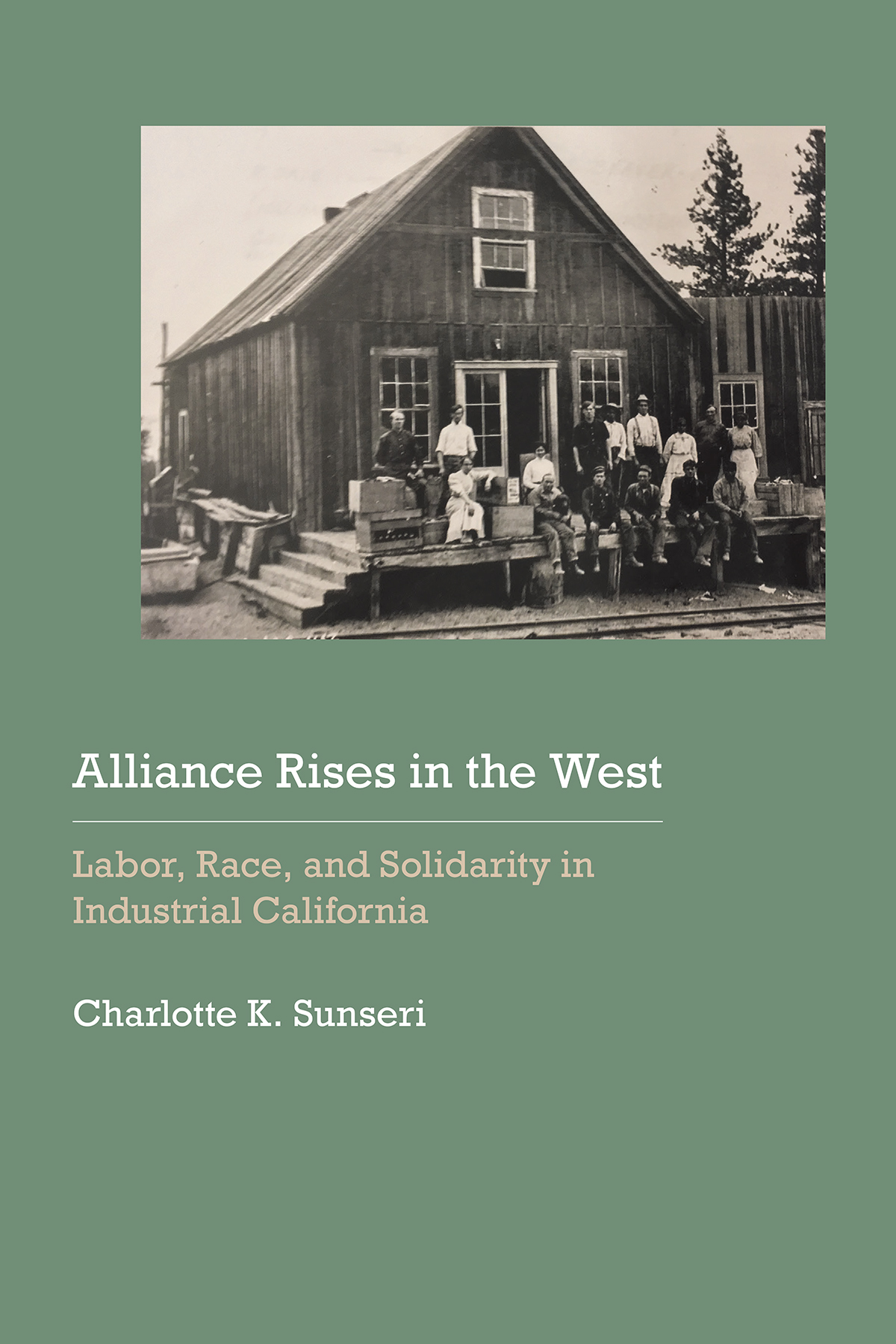

Alliance Rises in the West

Labor, Race, and Solidarity in Industrial California

Charlotte K. Sunseri

University of Nebraska Press and the Society for Historical Archaeology

2020 by the Society for Historical Archaeology

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image is from the interior.

Figures 26, 27, 28, and 32 originally appeared with the article Food Politics of Alliance in a California Frontier Chinatown, International Journal of Historical Archaeology 19(2):416431.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sunseri, Charlotte K., author.

Title: Alliance rises in the West: labor, race, and solidarity in industrial California / Charlotte K. Sunseri.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020. | Series: Historical archaeology of the American West | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020007863

ISBN 9780803299566 (hardback)

ISBN 9781496223272 (epub)

ISBN 9781496223289 (mobi) ISBN 9781496223296 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : ChineseCaliforniaHistory19th century. | MinersCaliforniaHistory19th century. | LaborCaliforniaHistory19th century. | Industrial relationsHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC E 184. C 5 S 966 2020 | DDC 979.4/004951dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007863

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

This work is the culmination of eight years of collaboration and friendship with the Mono Lake Kutzadikaa Paiute Tribe, and I want to extend a special thanks to Charlotte Lange, Leroy Williams, Jerry Andrews and Teri Jenkins, and Augie Hess. The fieldwork and research would not have been possible without the support of Jun Sunseri, the participants in and volunteers for the 2012 field program (Michael Boero, Roman Boiko, Julianne Cadden, Edward DeHaro, Robert Gelb, Nancy Johnson, Alexandra Levin, Anthony Salos, Rebecca Spitzer, Lily Van Osdol, and Megan Watson), Rob Cutthrell (botanical analysis), Alexandra Levin (faunal analysis support), Nancy Johnson (photographs of artifacts and Yerington letter transcription support), and Idelle Cooper and Blaine Cooper (photographs and figures). Fieldwork was conducted in the Inyo National Forest in accordance with the terms of a permit for archaeological investigations ( INF 120007 T ). The Inyo National Forest office also lent me the Passport in Time archaeological collection from Mono Mills, and the work greatly benefited from the assistance of Heritage Program manager Sarah Johnston. Many thanks to the staff of historical archives, including Jessica Maddox and Jacquelyn Sundstrand at UN Reno special collections (Reno, Nevada), Craig Castleton at California State Railroad Museum Library and Archives (Sacramento), Roberta Harlan at Eastern California Museum (Independence), and Sheryln Hayes-Zorn at Nevada Historical Society (Reno). The San Jose State University College of Social Sciences, particularly Dean Walt Jacobs and Shishir Mathur, provided funds to support this project at essential stages of its development. The tireless and insightful contributions of Rebecca Allen and valuable comments from two external reviewers, Don Hardesty and Carolyn White, along with Glen Gendzel and Robert Gelb, greatly improved this manuscript. Finally, I offer my sincere gratitude to the editors and staff of the University of Nebraska Press, particularly Matthew Bokovoy (senior acquisitions editor, Native American and indigenous studies) and Annalies Corbin and Rebecca Allen (series editors, Historical Archaeology of the American West).

Mono Mills, a Wild West Suburb

Well before this land became American soil, prospectors were drawn to the natural resources of the Sierra Nevada, including the area along the eastern edge of the Mono Basin. Paiute inhabitants mined obsidian from the nearby Casa Diablo volcanic outcrop and Mono-Inyo Craters. The world rushed in to mine gold and silver at Bodie during the late 19th century, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power came to this area in the mid-20th century to prospect for water to feed the Los Angeles aqueducts. The labor of generations has marked this landscape and left material traces. Historic gold rushes to this area significantly altered the region and its inhabitants in enduring ways.

This volume explores the microcosm of Mono Mills and considers labor tensions in capitalism, processes of racialization and discrimination, and class struggles in the Gilded Age gold rushes of California within the context of mining and logging near the boomtown of Bodie. The period of interest coincides with the aftermath of the Civil War, extending from about 1865 to the turn of the 20th century and thus spanning critical changes in American society. The 1849 rush to California was followed by an 1859 rush to the Comstock Lode in Nevada, as well as by lines of transportation opened by the transcontinental railroad, ever-increasing regulation of Chinese immigration, and pan-Indian resistance movements such as the Ghost Dance religion. Communities and towns were hastily built in what was once a solely Native American landscape, thus reflecting rapid mobilization made possible by powerful mining companies and railroad conglomerates. Construction of mining and company towns affected indigenous homelands and life, brought stasis of wage labor and inequity, and made power structures evident through the construction of ethnically and racially segregated neighborhoods.

The Town of Mono Mills

Mono Mills was built along the edge of the Sierra Nevada (Figure 1) and was occupied from 1880 to 1917. It came into existence to provide the booming town of Bodie with wood needed to shore up mine shafts and ceilings, to build commercial and domestic structures, and to provide fuel. Now the site of a state historic park, the boomtown of Bodie (Figure 2) became a destination for fortune seekers in 1874, when more than 10,000 miners, speculators, and entrepreneurs migrated there after the Comstock Lode dried up (Sprague 2003; C. Sunseri 2015a). Bodies population surges taxed the local wood supply, as wood consumption more than quadrupled nearly overnight (Sprague 2003). The Bodie Wood and Lumber Company began operating in 1878, but in 1881 the company reorganized as the Bodie Railway and Lumber Company (Piatt 2003:134) to meet this growing need by transporting wood milled from the Jeffrey pine forest around Mono Lake (Figure 3). Henry M. Yerington, as well as Bodies Standard Mine principals Seth Cook, Dan Cook, and Robert Graves, and a small circle of other stockholders financed the construction of Mono Mills and the lumber operation (Wedertz 1969:159; Canton and Canton 2011:57). The project gave Bodieites hope and enthusiasm for the future (Sprague 2003:105). To build the railway, 68 Chinese and 260 white men were paid $1.25 per day plus board, and many unemployed men had little option but to join the work gangs (Sprague 2003:105).

Next page