A WEARY LAND

Early American Places is a collaborative project of the University of Georgia Press, New York University Press, Northern Illinois University Press, and the University of Nebraska Press. The series is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more information, please visit www.earlyamericanplaces.com.

ADVISORY BOARD

Vincent Brown, Duke University

Cornelia Hughes Dayton, University of Connecticut

Nicole Eustace, New York University

Amy S. Greenberg, Pennsylvania State University

Ramn A. Gutirrez, University of Chicago

Peter Charles Hoffer, University of Georgia

Karen Ordahl Kupperman, New York University

Mark M. Smith, University of South Carolina

Rosemarie Zagarri, George Mason University

A WEARY LAND

Slavery on the Ground in Arkansas

KELLY HOUSTON JONES

The University of Georgia Press

ATHENS

2021 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Most University of Georgia Press titles are

available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed digitally

Library of Congress Number: 2020952835

ISBN: 9780820360201 (hardback)

ISBN: 9780820360195 (ebook)

For Jerry

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Like many working-class first-generation college students, I began as a business major, seeking training that I could leverage into a high-paying job. When I switched to history, my family became (understandably) nervous about my prospects. Thanks to professors and mentors at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, like Carl Moneyhon, the late C. Fred Williams, and Kristen Dutcher Mann, for showing me that I made the right choice. During my studies at the University of North Texas, Randolph B. Mike Campbell taught me how to roll up my sleeves for deep research in often overlooked sources. He was incredibly patient and generous with his time and I cherish his continuing friendship. Jeannie Whayne broadened my questioning about life on the ground for enslaved people. She understood my vision for this project from the beginning and never wavered in her confidence in me. I also benefited from Patrick Williamss sharp eye and sharper mind. I am grateful for research support provided by the University of Arkansas Department of History, the Mary Hudgins Research Fund, the Diane D. Blair Center of Southern Politics and Society at the University of Arkansass Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences, and the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

More scholars, archivists, and panelists advanced my thinking, research, and writing than can be listed here. In particular, the professionals at the University of Arkansas Librarys Special Collections, the Arkansas State Archives, and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Bowen Law School/Pulaski County Law Library provided invaluable assistance. Like everyone who studies Arkansas, I am also indebted to the experts at the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, and the Historic Arkansas Museum. Thanks to Story Matkin-Rawn for generously sharing the story of Reuben Johnson and to Debbie Liles for the source on Worthingtons trek to Texas. Special thanks to my anonymous reviewers who provided thorough readings that saved me from missteps, pushed my thinking, and increased the quality of the book. Remaining shortcomings are mine alone.

Thanks to Becky Howard for helping me navigate the National Archives, serving as my go-to Ozark expert, and always being willing to talk out historical problems whether in late-night ramblings or on the road to a conference. Thanks to my support system of colleagues (both at my first job at Austin Peay State University and at Arkansas Tech University), friends, and family. Alana and Carly are two of the best cheerleaders. I may not have achieved a life of luxury but I have found meaning in this work that would not have been possible without all of the folks mentioned above. Since beginning the project, my family has experienced earth-shattering losses that made research and writing seem trivial. I could not have survived any of it, and certainly couldnt have gotten back to work on this book, without Chris Jones, the best partner anyone could ask for.

A WEARY LAND

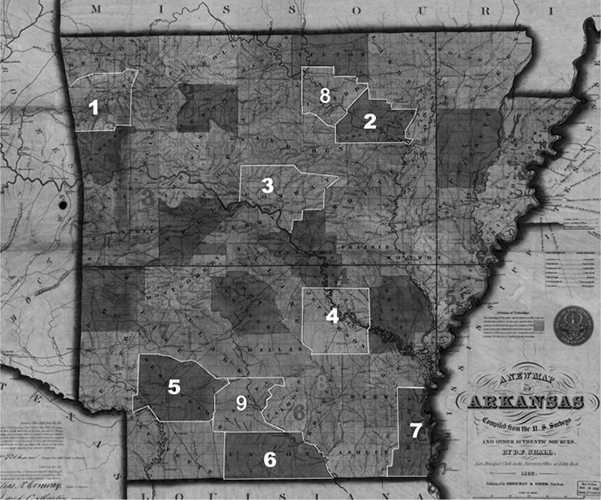

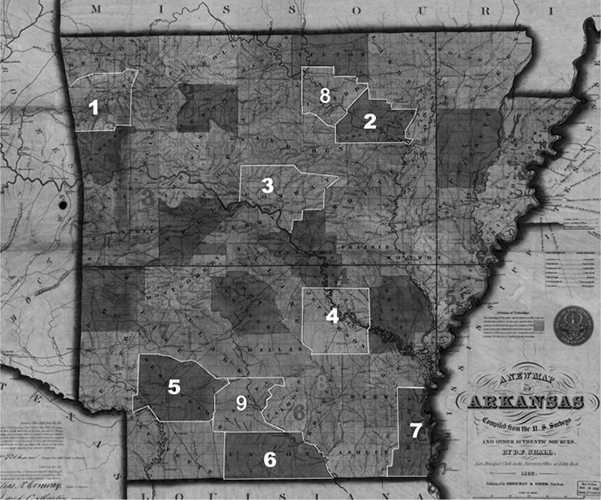

A New Map of Arkansas, 1852. Counties frequently mentioned in this book: (1) Washington; (2) Independence; (3) Conway; (4) Jefferson; (5) Hempstead; (6) Union; (7) Chicot; (8) Izard; and (9) Ouachita. Library of Congress.

Introduction

Reuben Johnsons life on a plantation south of Little Rock changed forever when he heard a man read from the Bible one Sunday. From that moment, Johnson became determined to be able to do the same. But he was an enslaved black manchattel, under the laws and conventions of Arkansas and the Southand therefore forbidden from achieving an education. Nevertheless, the determination to learn to read and write engulfed him, and Johnson found ways to teach himself. He listened to recitations of the alphabet outside the white childrens schoolhouse, and eventually he managed to secure a book to study on his own. Although his enslaver confiscated the book and whipped him for having it, Johnson raised money for another by gathering walnuts to sell to passing peddlers. This time, a hollow log housed the precious contraband. Johnson snuck into the woods to bring out one page at a time for studying in the quarters. Eventually, however, whites found him out. Again his book was seized, and again he paid for it in lashes. Johnson persevered, however, securing yet another book by enlisting the plantation wagoner to help him sell hay he had been gathering at night. Johnson again relied on a log to conceal his latest prize but now restricted his study to sessions in the woods. Johnson finally realized his dream of literacy after fleeing his enslavers in 1864 to fight for the United States Army against the Confederacy.

Reuben Johnson, like hundreds of thousands of other enslaved people across the South, made calculated use of space to navigate his bondage.

But the place where Reuben Johnson lived, worked, and resistedthe southern peripheryremains underrepresented on historys bookshelves. Scholars have devoted relatively little attention to places west of the Mississippi River, where, even as late as 1860, slavery was young and the terrain only thinly (yet rapidly) occupied by westward-moving settlers. Token mentions of slavery in Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, and northern Louisiana make their way into general histories, but the field requires more in-depth investigation into the daily lives of enslaved people on the southern fringes. Even renowned historian Walter Johnsons magisterial work on slavery in the Mississippi Valley, River of Dark Dreams, casts its gaze almost exclusively on the eastern side of the river when discussing points north of New Orleans.

To examine the experiences of Johnson and the 111,000 other men, women, and children enslaved in Arkansas is to explore bonded life in Arkansass youth as a state, position on the far side of the Mississippi River, lack of any truly urban centers, border with Indian Territory, and exponential growth of slavery in the decade before the Civil War all combine to form a landscape of bondage that cannot be adequately represented in studies that privilege the Southeast.

Next page