ARMENIA, AUSTRALIA

& THE

GREAT WAR

VICKEN BABKENIAN is an independent researcher for the Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Sydney. Vicken has written several articles on Australian international humanitarianism for peer-reviewed history journals. His research has been cited in radio and television documentaries on the First World War and its aftermath.

PROFESSOR PETER STANLEY is one of Australias most active military-social historians. Formerly the Principal Historian of the Australian War Memorial, where he worked from 1980 to 2007, he has been a research professor at UNSW Canberra since 2013. He has published twenty-nine books, including Lost Boys of Anzac (2014) and his Bad Characters was jointly awarded the Prime Ministers Prize for Australian History in 2011. Peter is president of Honest History and appears frequently in the media.

ARMENIA, AUSTRALIA

& THE

GREAT WAR

Vicken Babkenian & Peter Stanley

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley 2016

First published 2016

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Babkenian, Vicken, author.

Title: Armenia, Australia & the Great War / Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley.

ISBN: 9781742233994 (paperback)

9781742242286 (ebook)

9781742247656 (ePDF)

Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: Armenian massacres, 19151923.

World War, 19141918AtrocitiesTurkey.

Armenian massacres survivorsAustralia.

Humanitarian assistance, Australian.

ArmeniansAustraliaHistory.

World War, 19141918Participation, Australian.

Other Creators/Contributors:

Stanley, Peter, 1956 author.

Dewey Number: 956.620154

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Nada Backovic

Cover images TOP LEFT A deported Armenian woman and child. Armin T Wegner Wallstein Verlag, Gttingen. TOP RIGHT The Rev. James Cresswell, Miss Gordon, Hilda King and John Knudsen and some of the 1700 Armenian orphans at the Australasian Orphanage, c. 1923. Courtesy of Missak Kelechian. BOTTOM Two Australian Light Horsemen watch Armenian women sew at the Port Said refugee camp, c. 1918. James A. Cannavino Library, Archives & Special Collections, Marist College, USA.

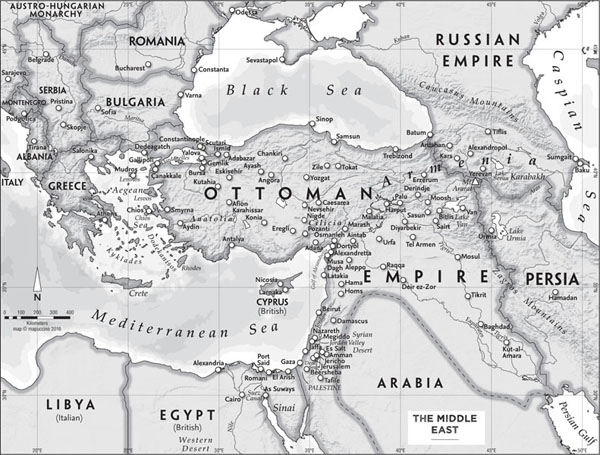

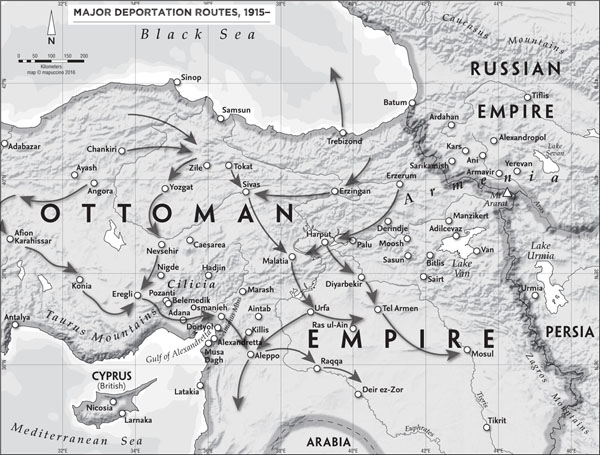

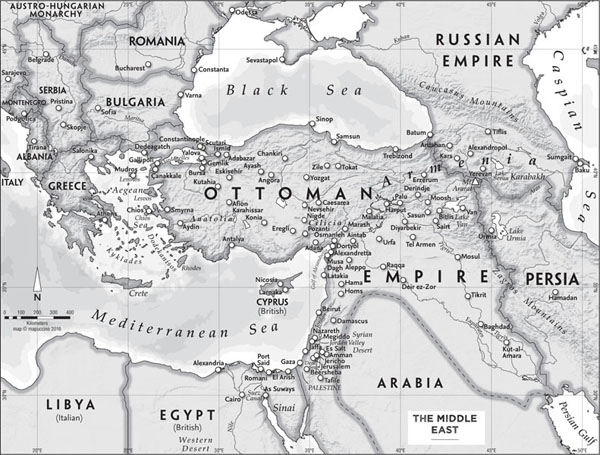

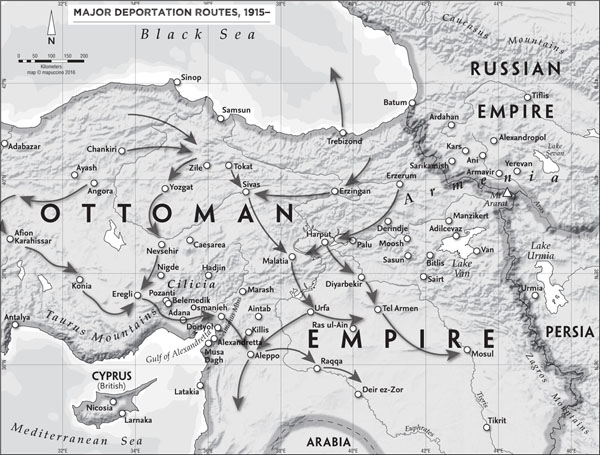

Illustrations Maps on pages viiiix and xxi by Gavin James, mapuccino

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The authors welcome information in this regard.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

To all those humanitarians who risk their lives to save others during war and genocide

AUTHORS NOTE

We have chosen to use place names and spellings that would have been familiar to Australians reading about the progress of the Great War in the early twentieth century, rather than their modern equivalents Trebizond rather than Trabzon, for example, and Moosh rather than Mu.

For Turkish personal names, and the names of organisations, we have tried to use those the Turks themselves would have used, retaining their distinctive accents. Among the Turks, bey was an honorific title meaning sir. Paa, which we have rendered pasha, following the practice of most English-speakers at the time, was a title given to generals and high-ranking statesmen.

PROLOGUE

SATURDAY, 24 APRIL 1915

On the afternoon of 24 April 1915 one of the most significant events in the military history of Australia and New Zealand began in the harbour of Mudros, just off the Greek island of Lemnos. The island had become the base for the great Anglo-French assault force assembling for the planned invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula that would occur the next day.

The broad harbour was full of ships of all kinds merchant ships, white-painted hospital ships and warships, from the smallest fishing trawler pressed into service to HMS Queen Elizabeth, the worlds newest and most powerful battleship. The transports carried some 75,000 troops, a polyglot force of men from Australia, Britain, France, India and New Zealand. Their task, beginning before the next dawn, would be to land upon the hostile coast of the Gallipoli peninsula and seize the forts defending the Dardanelles strait, the waterway leading to the Ottoman empires capital of Constantinople (now Istanbul). After what most expected would be relatively light fighting the Ottoman army was believed to be poorly equipped and trained, and restive under its German commanders the force was expected to move northwards and swiftly occupy the capital, which would soon come under the guns of the British and French battleships.

One by one that afternoon the transports and warships weighed anchor and steamed out of the harbour, some turning east to make directly for the peninsula, 130-odd kilometres across the Aegean Sea, and others turning west to round the island before heading eastwards for a rendezvous with destiny. The Australians, New Zealanders and Indians would land north of Gaba Tepe around a little bay later named Anzac Cove. A few hours later the British and French would land on either side of the mouth of the Dardanelles, soon becoming bogged down in the fight for Cape Helles. As is well known in the countries of at least three of the protagonists, the Gallipoli campaign, whether it was won or lost, became a part of the founding myths of Australia, New Zealand and Turkey, still described in epic, almost mythological terms a century on.

Just hours before the Anzac landing, the Ottoman authorities arrested about 230 Armenian political, religious, educational and intellectual leaders in Constantinople. Removed from their homes, the prisoners were taken to the police headquarters now Istanbuls Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum, on the Hippodrome, in what has become the centre of the citys heritage and tourist district. The arrests were a result of a directive sent by Mehmed Talaat, Ottoman minister of the interior, earlier that day. Among those arrested was German-educated Armenian Apostolic bishop Grigoris Balakian, whose brother, Haroutiun Balakian, lived in Melbourne. Within hours, as the Anzacs came ashore, Grigoris and his fellow prisoners were deported east by train from Haidar Pasha railway station on the Asiatic shore, arriving at Angora, now the Turkish capital of Ankara, about 500 kilometres away. One group of sixty-two were taken to Ayash, north-west of Angora, while the rest including Balakian were taken further to the north-east, to Chankiri. Only eight of the 230 survived: the rest disappeared without trace. Grigoris was one of the lucky few who were not murdered, and in April 1916 he escaped. With boldness and ingenuity, he disguised himself The arrests carried out on 24 April would become a blueprint for the rounding up of the Armenian elite throughout the Ottoman empire.

Next page