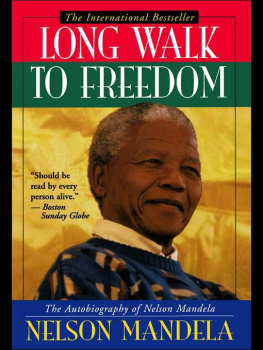

Nelson Mandela is an international statesman and Nobel Prize winner. He is an acclaimed orator and is the author of No Easy Walk to Freedom (1965) and Long Walk to Freedom (1994).

Andr Brink is an award-winning South African writer and critic. He is the author of several internationally acclaimed books, including A Dry White Season (1974).

Henry Russell, the editor of Let Freedom Reign, is the London-based author and editor of more than 18 books, including The Politics of Hope (also published by New Holland).

Henry Russell

Foreword by Andr Brink

For Sara, Meredith, Fabia and Esther.

This edition published in 2011 by New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd

London Cape Town Sydney Auckland

www.newhollandpublishers.com

Garfield House, 8688 Edgware Road, London W2 2EA, UK

80 McKenzie Street, Cape Town 8001, South Africa

Unit 1, 66 Gibbes Street, Chatswood, NSW 2067, Australia

218 Lake Road, Northcote, Auckland, New Zealand

Copyright 2011 introductory text: Henry Russell

Copyright 2011 speeches and images: see

Copyright 2011 foreword: Andr Brink

Copyright 2011 New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd

Henry Russell has asserted his moral right to be identified as the editor of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

ISBN: 978 1 84773 648 2 [print]

ISBN: 978 1 78009 118 1 [ePub]

ISBN: 978 1 78009 119 8 [Pdf]

Publisher: Aruna Vasudevan

Project Editor: Julia Shone

Inside design: Sarah Williams

Production: Melanie Dowland

Contents

Foreword by Andr Brink

Nelson Mandela: Myth Man Magician

Nelson Mandela

Myth Man Magician

a foreword by

Andr Brink

Years ago, among the green mountains of the Languedoc region in France, on my way to Carcassonne, I turned off the main route to follow a thin little side-road which brought me to a tiny village with only one paved street. The others were mere paths that branched off randomly, left and right, some of them no more than flights of steps hewn from the solid rock. Here and there villagers were going about their immemorial business: a cobbler in his workshop, a spinning woman, a baker stacking fragrant baguettes on a shelf, a sprinkling of children playing on what passed for a village square. The little place seemed lost in time and space. It might have been a hundred years ago, an unimaginable distance from the nearest town.

In one of the tortuous little side streets, along a steep incline, I noticed in a small square window on my right, set in a stone wall that might have dated from the Middle Ages, the bright colours of a sticker not much bigger than a postcard. It said, as I approached to take a closer look: LIBREZ MANDELA.

It seemed so out of place, so utterly pointless. And yet, as I felt my throat contract, this was wholly necessary and inevitable and necessary: for there was, literally, no corner or nook in the wide world where Mandela was not relevant and present. Only a few years later he was indeed set free, and what an unforgettable moment that was, when he strode from Pollsmoor Prison outside the town of Paarl, hand in hand with his then wife Winnie, towards the frenzied crowds massed along the road through the vineyards, towards Cape Town, towards the waiting world. A world that could never be quite the same.

A moment of exultation. But also a moment fraught with dire possibilities. For when in 1964 Mandela had gone from the Rivonia trial to the prison on Robben Island truly a place where a man had to abandon all hope of ever returning to the outside world the legacy he had left behind was encapsulated in one of the truly unforgettable speeches of our modern era culminating in those ringing words: It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die. During the 27 years of his captivity these words had continued to reverberate around the world: on the campuses of the USA and Western Europe, behind the Iron Curtain, in small clandestine gatherings and large auditoriums; they had acquired breadth and depth and the quality of prophecy and vision: such stuff as dreams and myth are made on. Now, emerging from prison, there was a real danger that the man could no longer match the myth. How could anyone live up to the expectations the world had dreamt about him: the hopes of the oppressed, the groans of the suffering, the imaginings of politicians, of the poor and the deprived all around the world, the unexpressed and inexpressible yearnings of the millions of women and men who believe that life could and should be different and more meaningful than the existence they had been relegated to?

Mandela himself tried to make it clear that he was merely human: I stand here before you, he said in Cape Town on 11 February 1990, in his very first speech after his release from prison, not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. But that was easier said than done. The miracle was that this was exactly what he achieved. He never betrayed the myth: in almost every imaginable respect he lived to the expectations of the world. But he never sacrificed his humanity warts and all he showed humanity what a human being could do, and be.

The story was told about his final journey through Europe, at the end of the first term of his presidency, when he voluntarily laid down the burden of office and went to take his leave from all the heads of state who had offered him and his people their support during his term of office; and how at the end of every exhausting day, he would summon all his secretaries (four of them, I was told, as he had too much energy for one or two), and invited them to sit on his bed before he went to sleep. Now tell me, he would ask of them, what have I done wrong today?

Can anybody, by any stretch of his or her moral or mental resources, imagine any other leader acting in this manner? To Mandela it came naturally; it was not an act (even though he could be a consummate actor when occasion demanded). Because, when all was said and done, he was a man among women and men and most particularly children.

It is because of the very humanness of his humanity for better or for worse that the way in which Mandela assumed the burden of being a man among people transformed the very ordinariness of his being into something magical. The famed Madiba Magic has endowed him with the almost uncanny ability to transcend the ordinary. At the time of our first free elections, Mandela made me believe: We have achieved the extraordinary. Now we can tackle the ordinary. Because in this country we have a human being in charge. No more. And certainly no less.

Part of his humanity resided in his resolve never to accept that the struggle to which he had dedicated his life, his long walk to freedom, could ever be over. Much of his energy went into the realization of his dream for a commission in charge of truth and reconciliation. Long after many of his colleagues including the unreliable and often unpredictable F.W. de Klerk, Mandelas second deputy president with whom Madiba had to share his Nobel Prize and to whom he had addressed some of his harshest (but eminently well-deserved) words at the end of the first day of the CODESA negotiations had faltered in their support of this remarkable enterprise (flawed as it may have been), Mandela remained as steadfast as Table Mountain.

Next page