First published 2012 by Museum Education Roundtable

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2012 Museum Education Roundtable

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Production and Composition by Detta Penna and Adriane Bosworth

ISBN 13: 978-1-611-32821-9 (pbk)

Tina R. Nolan and Cynthia Robinson

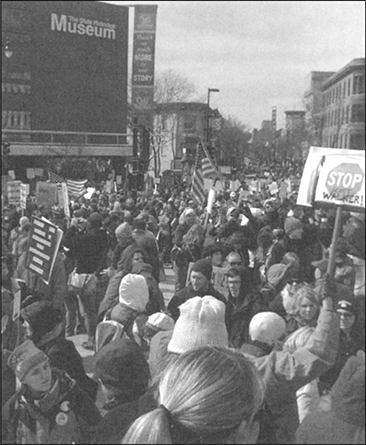

Tens of thousands of public service employees from across the State of Wisconsin descended on the capitol to protest Governor Scott Walkers plan to remove collective bargaining rights for unionized state workers. Governor Walker argued that this provision in his budget was necessary to close a massive budget gap, brought about by the 2008 financial meltdown that led to the current recession. As many as 100,000 teachers, police officers, factory workers, firemen, and nurses left their homes and families to march on the capitol square and camp in the capitol rotunda. Together they implored the governor to reconsider his plan. At the same time, supporters of the governors plan were mobilizing, making their way to the capitol to argue in favor of its implementation. Everyday life in the state had become contentious: Neighbors argued with neighbors, lifelong friendships ended, and public service employees faced vocal opposition in such unlikely places as their local grocery stores and restaurants. Students in classrooms asked their teachers to talk about what was happening - clearly a teachable moment and an opportunity to discuss democracy and civic dialogue, but union rules prohibited teachers from discussing any aspect of the conflict while on school property.

Feeling compelled to join the protest, I made my way to Madison from my home in Chicago. When I arrived I noticed, among the throngs of protesters, that several museums were located next to the capitol square. Were any museum educators standing alongside their fellow Wisconsin schoolteachers, marching in solidarity with them for teachers rights to bargain for salary, class size, and proper resources for public schools? After all, significant cuts to public education would have direct implications for museums and ultimately for museum workers. Consider this example: Less money for public schools means larger class sizes, fewer teachers, and a narrowed curriculum. A narrowed curriculum means less priority given to non-core subject areas like history, geography, and the arts. It also means fewer resources allocated for school field trips and outreach programs for schoolsparticularly those programs in non-core subject areas. Fewer teachers in public schools mean a drop in attendance for teacher professional development workshops provided by museums. A drop in attendance for school field trips, outreach visits to classrooms, and teacher workshops means a drop in revenue for museums. And a loss of revenue in museums means that museums must tighten their belts. When museums cut budgets, museum workers lose their jobs.

Journal of Museum Education, Volume 37, Number 3, Fall 2012, pp. 5-8.

2012 Museum Education Roundtable. All rights reserved.

Teachers and other public service workers from throughout the state of Wisconsin protesting at the state capitol in March, 2011. Photo by Mark Larson, Ed.D.

When I returned to Chicago, I contacted some Wisconsin museum educators, looking to invite them to attend discussion and support groups for teachers in the wake of the protests. While in conversation with one museum educator, I asked, What has it been like for you, to be smack-dab in the middle of this ongoing and massive public protest?

Well, the educator said, the numbers of visitors to the museum has really dropped.

Have you participated in the public demonstrations in any way? I asked.

I see the protesters every day, but, no, I havent taken part in the protest.

Granted, this was only one exchange with one person, and its an easy strategy to extrapolate out for the sake of making a point. Its entirely possible that other museum educators in the area were marching alongside their fellow teachers, and that still others had joined the hundreds of local protest marches organized across the state. But this exchange did give me pause. Why was this educator so removed from what was happening all over? Did this person fear taking a side in such a contentious debate? Were they instructed not to participate by museum leadership? Did this person not understand the potential implications that eliminating collective bargaining rights would bring? Did this educator feel ancillary to the public education system and not a direct part of it? Do other museum educators feel the same way? Are museum educators ready to take part in educational change efforts by actively involving themselves in the politics of education?

Ready or not, we are in a period of massive changes to systems set-up in the 20th century. The systems that worked in the Industrial Age (financial, educational, etc.) simply do not function in the global and networked Knowledge Age in which we currently operate. The worlds financial system will not return to its previous state. In the United States, there will be fewer federal and state dollars available to support the work of cultural institutions, and philanthropic giving will not look as it did during the 1990s. Our public education system, currently broken, will not be fixed, but will instead evolve into something quite different than what we experienced as students. As museum professionals, we have several questions to ask ourselves. Chief among them: What will the role of museums be in twenty-five years and how will museums sustain themselves? What role will museum educators play in the evolution of our public education system?

In this issue of the JME, we hear from museum professionals in the midst of navigating large socio-political changes across the globe. Guest Editors Asja Mandic and Patrick Roberts have gathered the voices and experiences of museum professionals from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, Israel, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. Together they examine museum education practices and museum operations in post-conflict societies. Elizabeth Merritt, Founding Director of AAMs Center for the Future of Museums, roots her article in the latest research about demographic, educational, political, economic, and environmental trends, and gives readers an opportunity to imagine how museum educators in this country might weather dramatic systemic shifts and lead change.