ALSO BY TEMPLE GRANDIN

Emergence: Labeled Autistic (with Margaret M. Scariano)

Thinking in Pictures: And Other Reports from My Life with Autism

Genetics and the Behavior of Domestic Animals (editor)

Livestock Handling and Transport (editor)

Animals in Translation (with Catherine Johnson)

Unwritten Rules of Social Relationships (with Sean Barron)

Developing Talents (with Kate Duffy)

Humane Livestock Handling (with Mark Deesing)

The Way I See It

Animals Make Us Human (with Catherine Johnson)

The Autistic Brain (with Richard Panek)

Temple Grandins Guide to Working with Farm Animals

Calling All Minds (with Betsy Lerner)

Navigating Autism (with Debra Moore)

The Outdoor Scientist (with Betsy Lerner)

riverhead books

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Temple Grandin

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Grandin, Temple, author. | Lerner, Betsy, author.

Title: Visual thinking : the hidden gifts of people who think in pictures, patterns, and abstractions / Temple Grandin ; with Betsy Lerner.

Description: Hardcover edition. | New York : Riverhead Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022006436 (print) | LCCN 2022006437 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593418369 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593418383 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Visual perception. | ArtPsychological aspects. | Thought and thinking.

Classification: LCC BF241 .G683 2022 (print) | LCC BF241 (ebook) | DDC 152.14dc23/eng/20220210

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022006436

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022006437

International edition ISBN: 9780593543115

Cover design: Tyriq Moore

Book design by Alexis Farabaugh, adapted for ebook by Maggie Hunt

pid_prh_6.0_141468764_c0_r0

To all the people who think differently

Contents

One

What Is Visual Thinking?

Two

Screened Out

Three

Where Are All the Clever Engineers?

Four

Complementary Minds

Five

Genius and Neurodiversity

Six

Visualizing Risk to Prevent Disasters

Seven

Animal Consciousness and Visual Thinking

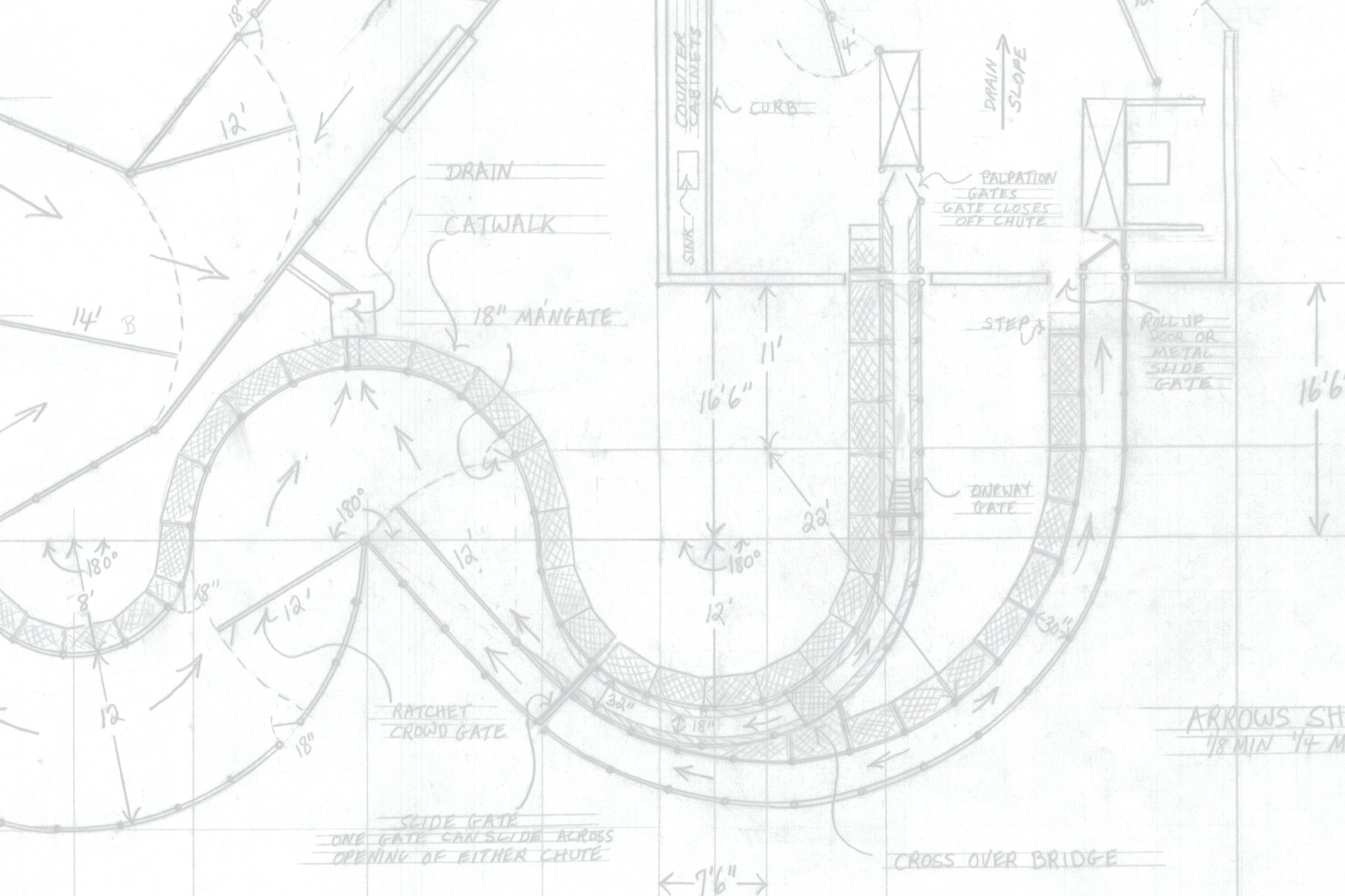

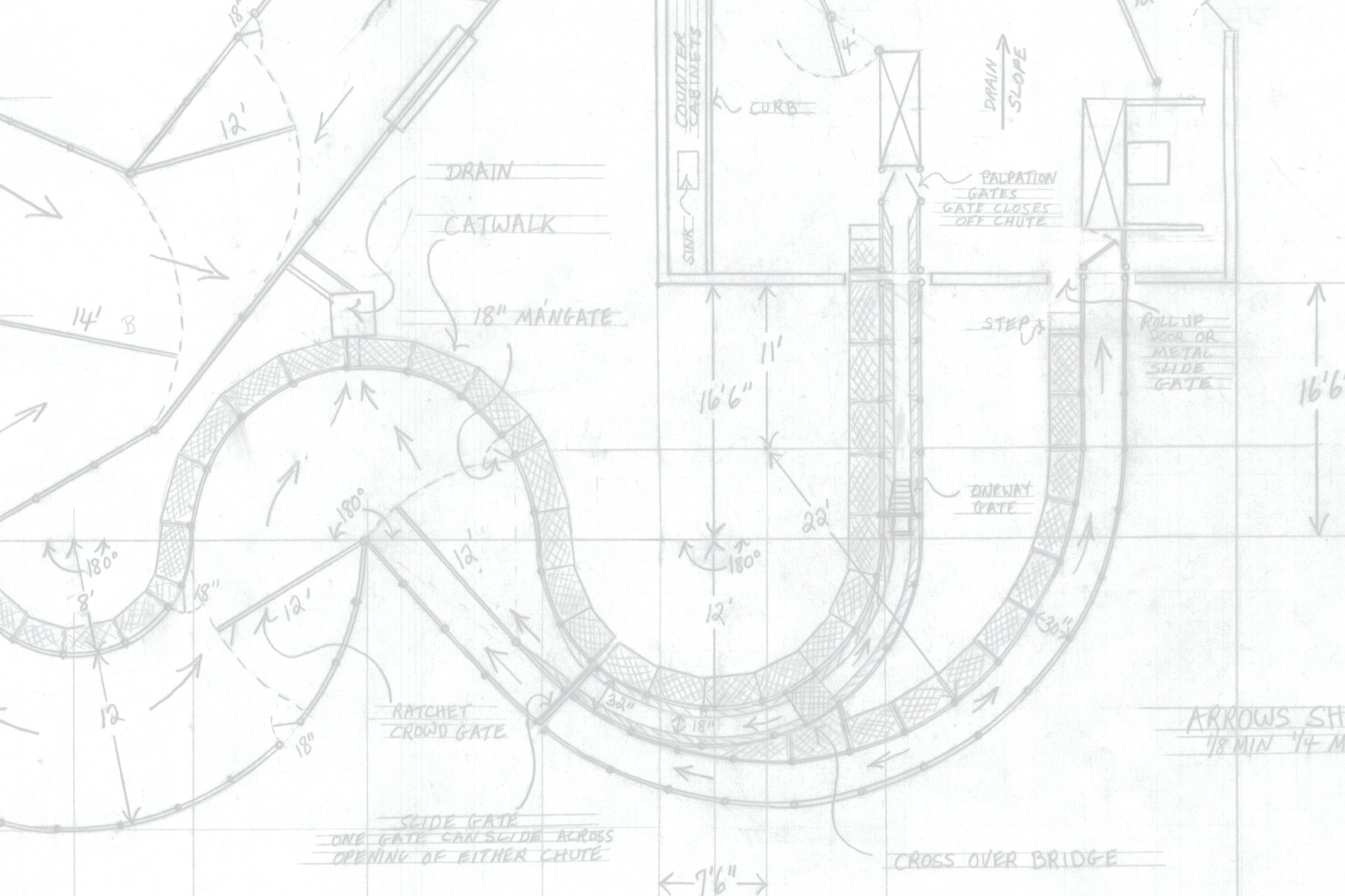

Drawings by Temple Grandin

Introduction

We come into the world without words. We see light, recognize faces, differentiate colors and patterns. We can smell and start recognizing tastes. We have a sense of touch and start grasping things and sucking our thumbs. Soon we start to recognize songs, which explains the universal existence of lullabies and nursery rhymes. Babies make lots of sounds. Mama and Dada are more random than anxious new parents want to believe. Gradually, language gains ascendancy: By one and a half, most toddlers will have a bunch of nouns and verbs under their belts. By two, they start to make sentences. By the time most children go to kindergarten, they can speak in complex sentences and understand the basic rules of language. When it comes to communication, language is the water we drink, the air we breathe.

We assume that the dominance of language forms not only the foundation of how we communicate, but also the foundation of how we thinkand in fact for centuries, we have been taught to believe just that. The seventeenth-century philosopher Ren Descartes cast a long shadow when he wrote, I think, therefore I am. Specifically, Descartes claimed that it is language that separates us from beasts: our very humanity was predicated on language. Flash forward a few hundred years, and we are still describing theories of mind based primarily on language. In 1957, linguist Noam Chomsky published his groundbreaking book Syntactic Structures, which claims that language, specifically grammar, is innate. His ideas have influenced thinkers for more than half a century.

The first step toward understanding that people think in different ways is understanding that different ways of thinking exist. The universally accepted belief that we are all hardwired for language may be why it took me until I was nearly thirty to understand that I am a visual thinker. I am also autistic, and I didnt have language until I was four. I didnt read until I was eight, and that was only with considerable tutoring in phonics. The world didnt come to me through syntax and grammar. It came through images. But unlike what Descartes or Chomsky might have expected, even without language my thoughts are rich and vivid. The world comes to me in a series of associated visual images, like scrolling through Google Images or watching the short videos on Instagram or TikTok. Its true that I now have language, but I still think primarily in pictures. People often confuse visual thinking with vision. We will see throughout this book that visual thinking is not about how we see but about how the brain processes information; how we think and we perceive.

Because the world I was born into did not yet distinguish between different ways of thinking, it was disconcerting to discover that other people didnt think the same way I did. It was like being invited to a costume party and discovering I was the only one wearing a costume. It was difficult to fathom the differences between most peoples thought processes and my own. When I figured out that not all people think in pictures, it became my personal mission to discover how people do think, and to find out if there were other people like me. I first wrote about this in my memoir, Thinking in Pictures, twenty-five years ago. Since then, Ive continued to investigate the prevalence of visual thinking in the general population through research of the literature; close observation; conducting informal surveys at the hundreds of autism and education conferences Ive addressed; and talking to thousands of parents, educators, disability advocates, and people in industry.

It wasnt exactly a eureka moment, because it dawned on me gradually rather than all at once, but I came to see that there were two different kinds of visual thinkers. Though I couldnt prove it at the time, I recognized a kind of visual thinker who was distinct from me. This is the spatial visualizer who sees in patterns and abstractions. I first became aware of this distinction while working with various kinds of engineers, machinery designers, and welders. Later, I was ecstatic to see my observations confirmed in the scientific literature. The work of the researcher Maria Kozhevnikov showed that there are object visualizers like me, who think in pictures, and, as I suspected, a second group of mathematically inclined visual-spatial thinkers, an overlooked but essential subset of visual thinkers, who think in patterns.