Speaking French in Louisiana, 17201955

SPEAKING

FRENCH

IN LOUISIANA

17201955

LINGUISTIC PRACTICES OF THE

CATHOLIC CHURCH

SYLVIE DUBOIS,

EMILIE GAGNET LEUMAS, AND

MALCOLM RICHARDSON

Louisiana State University Press Baton Rouge

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2018 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Arno Pro

Printer and binder: Sheridan Books

All maps and charts were drawn by Gabriele Richardson.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Dubois, Sylvie, 1963 author. | Leumas, Emilie Gagnet, 1958 author. Richardson, Malcolm, 1947 author.

Title: Speaking French in Louisiana, 17201955 : linguistic practices of the Catholic Church / Sylvie Dubois, Emilie Gagnet Leumas, and Malcolm Richardson.

Description: Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019261| ISBN 978-0-8071-6844-8 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 978-0-8071-6845-5 (pdf) | ISBN 978-0-8071-6846-2 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Catholic ChurchLouisianaHistory. | French languageReligious aspectsCatholic ChurchHistory. | Language question in the churchLouisianaHistory. | CommunicationReligious aspectsCatholic ChurchHistory. | English languageReligious aspectsCatholic ChurchHistory.

Classification: LCC BX1415.L9 D83 2018 | DDC 282/.763dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019261

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would never have been written without the generous involvement of the Archdiocese of New Orleans, which permitted us to use their archive materials, records, letters, administrative documents, and directories. They also provided us much appreciated, comfortable working space to consult files and records.

Our deepest thanks go to Charles Nolan, retired archivist of the Archdiocese of New Orleans, and John J. Treanor, former vice-chancellor of the Archdiocese of Chicago, for their guidance in suggesting where we might find relevant material and for always being available to discuss Catholic Church history. We also owe much to the archivists who shared the research material at their institutions: Barbara Dejean at the Diocese of Lafayette, Kevin Allemand at the Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux, Ann Boltin and Rene Richard at the Diocese of Baton Rouge, and Monte Kniffen at the Provincial Redemptorist Archives in Denver.

We are grateful for the support of a number of institutions and individuals. In particular, the Center for French and Francophone Studies at LSU funded many long hours of fieldwork at the Archdiocesan Archives and provided financial support for archival research trips at international locations: the Centre des archives doutre mer in Aix-en-Provence, France; the Archives Nationales de France in Paris; and the Sacred Congregation of the Propaganda Fide in Vatican City. We are indebted to the PhD graduate students enrolled in LSU French seminars in 2013 and 2014. They helped Emilie Leumas and Sylvie Dubois to extract and catalog more than nine thousand letters to build the 18031859 Antebellum Correspondence database.

Special thanks to professor emeritus Jay Edwards of the LSU Department of Geography and Anthropology, for encouraging us to trace the linguistic history of the Louisiana Church from its colonial past; to Albert Camp, who read and commented on the complete manuscript; and to the anonymous reviewer who provided constructive criticisms on an earlier draft. Gabriele Richardson worked tirelessly to adapt and redraft our charts and maps, using ArcGIS and other sophisticated software to bring them to professional standards, while checking with painstaking care the statistical data on those figures. The completion and editing of the manuscript were facilitated by the Louisiana Board of Regents, which awarded a research ATLAS grant to Sylvie Dubois in the 201516 academic year.

Most of all, we are indebted to three hundred years of Louisiana Catholic priests who wrote sacramental records. Their patient attention to duty and, as our study will show, their attention to the language needs of the faithful unwittingly wrote an important chapter in Louisianas sociolinguistic history.

Speaking French in Louisiana, 17201955

INTRODUCTION

I am getting too old for my words to have any weight with you. What I say, instead of sinking in, slides off, leaving no impression. I deem it necessary that a younger man take charge of you, and perhaps his word may have more effect than mine, said the seventy-two-year-old pastor Father Joseph Subileau to his parishioners from his pulpit in the spring of 1913. Father Subileau had officiated faithfully for forty-eight years as pastor of St. Augustine Church in New Orleans. But his wistful farewell was the result not of age or debility or, despite what he said, the need for a more youthful pastor. As reported by the New Orleans Times-Democrat in 1913, everybody in his parish understands French perfectly, but the younger generation is being taught their catechism in English; they make their confession in English, and they listen with more interest to sermons in English.

A devoted priest, Father Subileau felt a profound responsibility toward his parishs survival. Since he did not feel sufficiently at ease with the English language to carry on his ministry, he stepped down to avoid losing some of his flock. In his last address, he gave his blessing to his successor, a young priest who spoke both languages fluently and who could minister to the congregations language requirements. In a way, Father Subileaus departure encapsulates much of what is found in the following pages: a proudly francophone church carefully measuring the linguistic preferences of its parishioners and willing to make a painful change to retain its faithful.

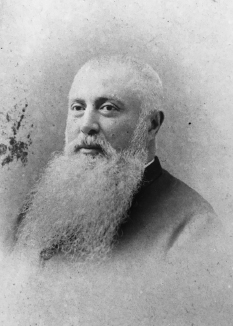

Father Joseph Subileau, pastor of St. Augustine Church. (Courtesy of the Office of Archives and Records, Arch-diocese of New Orleans.)

Social and economic influences from the turn of the nineteenth century to the mid-1950s created the necessity for Francophones to learn English in Louisiana, a necessity that was negotiated in different ways and at different paces by institutions and communities. Within the state government, the change, at least for official documents, was largely completed in the first decade following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Within the Catholic Church, in many ways a more powerful and stable social structure than the state in south Louisiana, the change was more long-term and cautious but also more sensitive to the language needs of the people. The fact that church parishioners in New Orleans could still attend Father Subileaus sermons in French on the eve of the First World War may surprise someone living outside of Louisiana (and some natives, too). Searching only the archives of the state government, scholars would naturally be persuaded that south Louisiana was an anglophone culture from the early nineteenth century. However, church writing practices from the eighteenth century until the 1960s offer another picture. A quick look at nineteenth-century church archival material is sufficient to appreciate the extensive use of both French and English; the more measured look taken in this book shows that the church, like Father Subileau, was willing to go to greater effort than the state to make certain that Anglophones and Francophones were accommodated.