Women and Power in Zimbabwe

Women and Power in Zimbabwe

Promises of Feminism

CAROLYN MARTIN SHAW

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield

2015 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015950095

ISBN 978-0-252-03963-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-252-08113-2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-252-09772-0 (e-book)

Contents

Illustrations

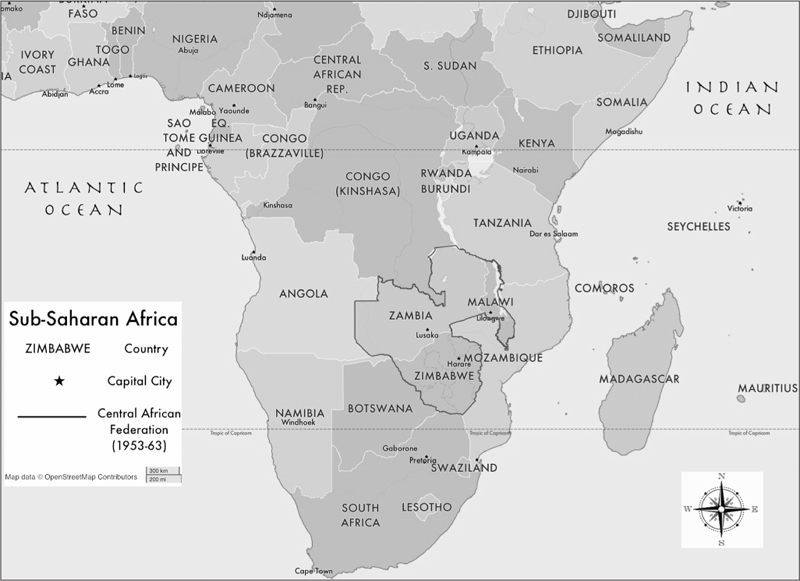

MAP

Sub-Saharan Africa, featuring Zimbabwe and the Central African Federation

FIGURES

Acknowledgments

M any people and many years, many celebrations and many disappointments went into the making of this book. I would like to acknowledge the women in Zimbabwe who were willing to put thoughts into words in answer to my questions and the members of NGOs who opened their doors to me. Young women and men in the city keenly engaged my concerns, all the while teaching me about what mattered to them. My colleagues who chewed over ideas with me and my neighbors in University of Zimbabwe housing who took me into their confidence and who allowed their children to freely visit my home were crucial to my getting a feel of what life was like for them. Those who supported this project include the wonderful professional staff at the National Archive of Zimbabwe and the secretaries and lecturers in the African Studies Department at the University of Zimbabwe.

This book project traveled with me around the world. Starting at my home university, Don Brenneis, Shelly Errington, and Dan Linger read early drafts of some of the chapters. Jim Clifford and May Diaz stepped in at vital moment to keep the project on track. Other colleagues in the anthropology department were unfailingly encouragingOlga Najera-Ramirez, Loki Pandey, Judith Habicht-Mauche, Lissa Caldwell, and Anna Tsing. As graduate research assistants, Michelle Rosenthal and Kristen Cheney helped organize my archive and track down data. On-campus discussions with Aaron Montoya and Sarah Chee about their research in Mozambique and South Korea often led to my musing about women and life in Zimbabwe. Happily, they engaged and read my work, much to its benefit. Melissa Hackman, a recent graduate from our program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, has cheered me on throughout this process and also provided excellent critiques of my work. In the town of Santa Cruz, a former student, now a writing teacher, Andy Couturier, with his asymmetric writing process, moved me to try a new way of putting ideas together. In Chicago and Gainesville, Florida, I was inspired by the work of Florence Babb, Mary Moran, Fran Mascia-Lees, Martin Manalansan, and Louise Lamphere as well as critiqued by Luise White and Marit Ostebo. Anthropologists from around the country who gave me a stage to present portions of the book or who shared their insight with me include Brackette Williams, Betty Harris, Barbara Joans, and Naomi Katz. In Hong Kong, my writing partners, Virginia Mack and Susan Fiksdal, looked at my work with fresh eyes and asked new questions. Sarah Rabkins able editing helped ready the manuscript for the publisher. Finally, this well-traveled manuscript found a wonderful home at the University of Illinois Press, where acquisitions editor Daniel Nasset read it and found anonymous reviewers willing to give constructive criticism of the project. What a joy it was to find that they grasped what I was doing and knew how I could build on it. The University of Illinois Press has been good to me: they encouraged my participation in the production process; Barbara Wojhoski gently massaged my prose; and Jennifer Holzner picked through my photos and ideas and came up with a cover design that I could not have imagined. Jennifer Comeau had just the right degree of structure and openness in managing the books production.

My friends and family may not be familiar with the contents of this book, but their love and care have sustained me in its making. Bill Shaw, who has been with me through the thirty years that this book covers, never lost confidence in my ability to finish the book; though he completed a dozen books in the time it took me to finish this one.

The book contains a revised version of my article Sticks and Scones: Black and White Women in the Homecraft Movement in Colonial Zimbabwe, Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Context , 1 (2), 25378. Map 1 was drafted by OpenStreetMap contributors. Photos of Dorothy Gona and Sheila Chikoore appear in chapter 4 with permission of the photographer, Birgitta Lagerstrom.

Women and Power in Zimbabwe

Introduction

What it is, she sighed, to have to choose between self and security.

Tsitsi Dangarembga, Nervous Conditions

T his book is about fulfilled and unfulfilled promises. It examines the promise of feminism to empower women and bring social and political equality to both men and women. I try to convey the varied effects of feminism in Zimbabwean social life, focusing on instances that seemed to promise women a better life and led them to believe in their own potential to influence politics. Women felt that they had been promised gender equality, and many continue to feel the betrayal of the governments promise to care about them.

In 1980 Zimbabwe came into existence to the strains of Rastafarian singer-songwriter and political icon Bob Marleys revolutionary anthem, Zimbabwe:

Every man got a right to decide his own destiny,

And with this judgment there is no partiality.

So arm in arm, with arms, we will fight this little struggle.

In the struggle against a white supremacist regime in the settler colony of Rhodesia, two separate and competing liberation armies marched toward a single socialist goal, which included the emancipation of women, with women combatants in war and empowered mothers in the countryside as their prime examples of success. But Zimbabwe did not live up to its promise. By the end of its first decade, the Zimbabwean state, under the leadership of Robert Mugabe, had denied freedom of movement and assembly to urban women, had allowed deep corruption among its officers, and had massacred tens of thousands of its own citizens, primarily members of the ethnic group predominant in the other liberation army that had helped bring independence. Incredibly, a short-lived prosperity followed this upheaval, but that ended in an awful downward spiral of increasing inflation and brutal state-orchestrated violence. What happens to feminism under these varying conditions? In this book, I argue that black women in Zimbabwe were paradoxically primed for feminism during the colonial period. Though womens resolve was greatly tested just where they thought they had their best allies, especially in the armed forces during the liberation struggle, feminism held the lure of a better life for many. As the luster of independence wore off, feminism seemed like cruel optimism, fighting for a better life when the government had become the enemy of the good. Women responded to this in different ways. Some made accommodations to the new regime; others confronted it head on, while most combined feminist ideals with more-conventional feminine powers.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.