2007 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Jacquline Johnson

Set in Baskerville MT

by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, Martha S.

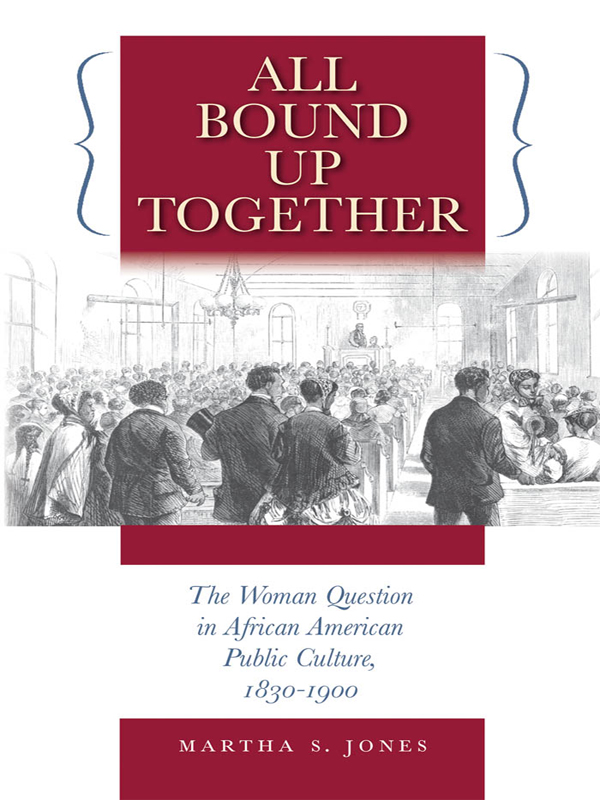

All bound up together : the woman question in African American public culture, 18301900 / Martha S. Jones.

p. cm. (The John Hope Franklin series in African American history and culture)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8078-3152-6 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8078-5845-5 (pbk.: alk. paper)

eISBN: 9780807888902

1. African American women political activistsHistory19th century. 2. African American womenHistory19th century. 3. African American womenSocial conditions19th century. 4. United StatesRace relationsHistory19th century. 5. Sex roleUnited StatesHistory19th century. 6. Womens rightsUnited StatesHistory19th century. 7. FeminismUnited StatesHistory19th century. 8. African AmericansPolitics and government19th century. 9. Community lifeUnited StatesHistory19th century. 10. African AmericansSocial conditions19th century. I. Title.

E185.86.J663 2007

305.48'896073009034dc22

2007010367

cloth 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1

paper 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1

Parts of Chapters 5 and 6 appeared earlier, in a somewhat different form, in Make Us a Power: African-American Methodists Debate the Rights of Women, 18701900, in Women and Religion in the African Diaspora, ed. R. Marie Griffith and Barbara D. Savage (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), and are reprinted here with permission.

Introduction

When African American poet and essayist Frances E. W. Harper took the podium during the inaugural meeting of the American Equal Rights Association, she spoke with both trepidation and conviction. Aiming to set forth a creed that might guide the fledgling womens rights organization, Harper declared: We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity. The year was 1866, and the nation was in the midst of what Harper termed a grand and glorious revolution. In the wake of the Civil War, all Americansespecially those of African descentwere engaged in a highly charged debate over freedom, citizenship, and the nation itself. Harper argued that any endeavor to transform the standing of American women required consideration of societys weakest and feeblest members alongside those individuals with their hands across the helm. In making her case, Harper drew upon her vantage point as a colored woman who, she explained, had felt every mans hand against her, and hers against every man. Using the term man as a universal, Harper underscored how race and gender intersected in her experience of oppression.

Harper, a relative newcomer to public speaking, had recently endured a series of personal degradations. After the death of her husband, she explained, a neighbor attempted to seize the few possessions left to Harper and her four children. In this circumstance, Harper understood herself to be bound up with the fate of the many American women who were deprived of meaningful property rights. Harper then told the audience of the difficulties she encountered when searching for a new home. She felt unwelcome in the many cities that limited her access to streetcars and discriminated against her in the housing marketthis had been the case even in Philadelphia, the city of brotherly love, and in Boston, where she finally settled. Thus, Harper cast herself as bound up with the burdens of blackness and the myriad injustices that flowed from race, as well as sex. But, if being an African American woman in the mid-nineteenth century might have engendered self-doubt, in Harper it fostered confidence and conviction. She was among the unprivileged class of Americans, yet Harper held herself out as the embodiment of the countrys crossroads. The most vexing challenges of freedom, citizenship, and the nations identity were all bound up together in her.

The life of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper vividly illustrates the multifaceted lives of mid-nineteenth-century African American female activists. Born to free parents in the slave state of Maryland and orphaned at three, Harper was raised by her uncle, William Watkins, a teacher and Methodist minister. Her early life was spent working as a domestic and then a teacher. Harper began her public life as a writer in the antebellum decades. She went on to defy convention by penning poetry, prose, and polemic in the black press. As a teacher, she accrued important insights into the educational challenges of the Reconstruction era. In 1866, she took the podium at the first postwar womens rights meeting. Over the course of her life, Harper was celebrated as an antislavery and civil rights advocate, a religious worker, journalist, womens suffragist, fraternal order affiliate, poet, essayist, and commanding public speaker. She well knew the many convergences that characterized nineteenth-century America, and she urged her audience memberswho were variously black and white, male and female, northern and southern, young and no longer youngto see them too. Her ideas reflected antebellum political culture, in which civil rights and womens rights had been intertwined. But she also spoke to the challenges facing a new generation of men and women who were navigating the meanings of freedom and citizenship in a world where earlier alliances appeared fragile. We are all bound up together, Harper urged, and with this she placed African American women at the center of the centurys greatest challenges.

All Bound Up Together explains how African American activist women, who occupied what was termed by many a marginal position in public life during the 1830s, became visible and authoritative community leaders by the 1890s. Across these seven decades, black female activists transformed their public standing through a process that was always bound up with the shifting fortunes of all black Americans. Three generations of women, often with male allies, engaged in a sustained and multifaceted debate about women in public life. Black womens prospects for public engagement were bound up with the revolutions and reforms that transformed American society over the century: slavery and abolitionism, womens rights, war, emancipation, institution building, the Fourteenth Amendment, and Jim Crow. Among African American activists, the nineteenth-century womens movementthe collective processes by which women asserted rights and claimed a central place in public lifeoccurred not within a distinct female sphere but in those spaces that men and women shared: churches, political organizations, mutual aid societies, and schools.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Frontispiece, Iola Leroy; Or, Shadows Uplifted