Copyright Jack Saunders 2019

The right of Jack Saunders to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 3339 7 hardback

First published 2019

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Deanta Global Publishing services

The idea for this book first took shape in 2005. At the time, I worked as a secretary in a health centre in Suffolk, taking out whatever time I could from database entry to read revolutionary tracts and argue politics online. I was in the office when I read about a wildcat strike by the baggage handlers at Heathrow, who had walked out in solidarity with their workmates in the outsourced catering company Gate Gourmet. I noticed that one consistent trope recurred in press coverage of events the idea that industrial relations at Heathrow were reminiscent of the 1970s.

As a child of the 1980s, this refrain fascinated me. What did it mean to say that the baggage handlers attitudes and behaviour pertained to this earlier era? Why were these practices now so alien to most other workplaces and to my own, rather moribund, trade union? Fourteen years later, this book is the result, above all, of trying to answer those questions in a more general form. Where does the readiness to confront ones employer collectively come from? What produces solidarity? What was the reality of the post-war industrial conflict that remains so important in popular narratives of Britains contemporary history?

That the answers to those questions eventually took shape as this monograph is thanks to the assistance of a large cast of people. Dr Michael Collins helped enormously in relating the work to the wider field of modern British history. Professor David DAvrays guidance on theories relating to rationalities was vital, as were Professor Margot Finns comments on early draft chapters. Professor Jon Lawrence and Professor Lawrence Black were both kind enough to read an early draft of the full manuscript and gave excellent advice on how to improve it. Without the fine work of the archivists at the Modern Records Centre, this book would have been impossible.

Professor Roberta Bivins and Professor Mathew Thomson have been hugely generous with their time, offering advice, support and encouragement throughout the final preparation of the manuscript. Dr Jenny Crane, Dr Jane Hand, Dr Natalie Jones and Dr Gareth Millward have all been wonderful co-workers over the past three years; their insight has been ever useful in my development as a historian, their willingness to listen to my endless nonsense more vital still.

The preparation of the initial proposal was enormously aided by advice given by Dr Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite and Dr Andrew W. M. Smith, as well as in seminar sessions at the Institute of Historical Research and at the University of Warwick Early Career Researcher (ECR) Writers Group. Professor Mark Philp was kind enough to make suggestions on how to improve it. The whole process of finally preparing the manuscript was improved greatly by Tom Dark, commissioning editor at Manchester University Press, to whom I shall be eternally grateful.

The friendship of many excellent young historians has sustained me through the ordeal of nervously committing my thoughts to paper. The constancy of Dr Harry Stopess assertions of my value as a historian and person, even when my own belief flagged, has been a source of comfort. Dr Camila Gatica Mizalas encouragement and good humour are something every historian should have at their side. Thanks also to Dr Ben Mechen for listening to me prattle on about car workers after every European history class we taught.

I shall also be forever grateful to all the trade unionists who gave their time to be interviewed and to many other friends in the labour movement whose insight was invaluable to the project. Particular thanks go to Millie Wild, a great friend and comrade, happy to sustain a continuous multi-year ongoing conversation about car-factory trade unionism.

Finally, without ever consciously consenting to it, my family have given an enormous amount of energy to this project. My brother, Simon Saunders, put up with me as a lodger for seven long years, and was still good-hearted enough to listen to me ranting about car workers every other day. My mum, Kate Saunders, is a far better writer than I will ever be and the best proofreader anyone could hope for. Both she and my dad, Giles, have been as kind and loving as any son could ever wish for. Finally, thanks must go to Dr Lucy Dow, my partner, whose support, love and general intellectual brilliance are all a massive presence in this book.

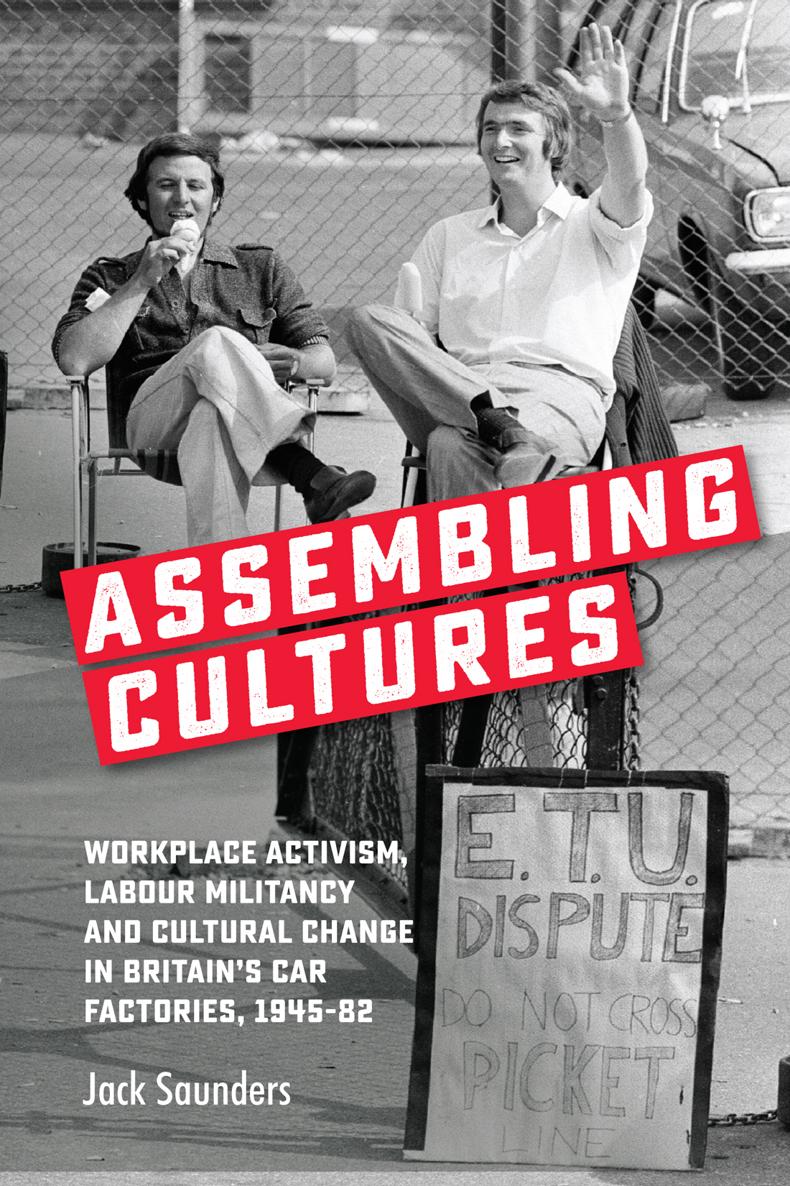

Theres more than just good humour behind the geniality of Woolfie, the man with his hands round the throat of the Chrysler motor company.

In 1973, 156 electricians at Chryslers Coventry Stoke Aldermoor engine factory went on strike for thirteen weeks, demanding the company fulfil a promise made months earlier to raise their salaries by 250 a year, a promise waylaid by Phase Two of the Heath governments statutory wage restraint programme. The electricians labour was vital to maintaining continuous production across Chryslers factories and without it the possibility of temporary shutdowns and even redundancies was soon raised. Towards the end of the dispute, the company was threatening to sack 8,000 employees if the strike didnt end within a week and even discussed pulling out of Britain entirely.

At the centre of all this was Woolfie Goldstein, the senior shop steward for the factorys branch of the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunications and Plumbing Trades Union (EEPTU). After thirty-three years as a relatively anonymous factory worker, in the autumn of 1973, he was cast as wrecker-in-chief of Chrysler UK. WOOLFIE WIELDS THE BIG STICK, blared the front page of the Daily Express on 26 September 1973, broadcasting the electricians plans for further disruption.