2011 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

C 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Reineke, Sandra.

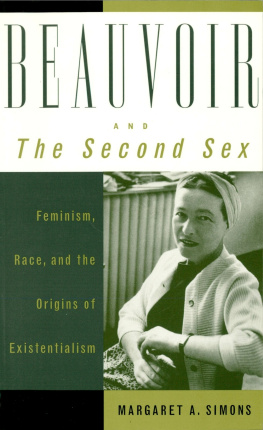

Beauvoir and her sisters : the politics of womens

bodies in France / Sandra Reineke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-252-03619-4 (hbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN -10: 0-252-03619-0 (hbk. : alk. paper)

1. FeminismFranceHistory20th century.

2. Feminist literatureFranceHistory and criticism.

3. CitizenshipFrance.

4. WomenPolitical activityFrance.

5. WomenSexual behaviorFrance.

6. WomenIdentity.

7. Beauvoir, Simone de, 19081986Criticism and interpretation.

I. Title.

HQ 1617. R 43 2012

305.420944dc22 2010046892

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MY WORK ON THIS BOOK has benefited from the help and support of many individuals, institutions, and research facilities. At Indiana University, where this study was conceived, I wish to thank my mentor, Jean C. Robinson, who inspired, trained, and guided me, as well as the universitys librarians, who aided me in hunting down needed materials. I am also thankful to the librarians at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, at the Bibliothque nationale de France and the Bibliothque Marguerite Durand in Paris, and at the University of Idaho in Moscow, Idaho, where I am now working. I am particularly grateful to Nancy Young, who on many occasions offered her help with finding copies of the womens magazine Elle examined for this study.

I am also grateful to my colleagues at the University of Idaho, particularly Kathy Aiken, Don Crowley, John Mihelich, Sarah Nelson, and Debbie Storrs, who have been loyal and supportive advocates of my work and research interests, and Kelli Schrand, whose support is unparalleled. Institutional support came from the University of Idaho Research Office, which provided me with an opportunity to present some of the findings of my study at scholarly conferences. I am indebted to Yolanda A. Patterson, who co-organized the Tenth Simone de Beauvoir Society International Conference in Torino, Italy, in 2002, and Dawn Marley, organizer of the international conference Francophone Womens Magazines Inside and Outside France at the University of Surrey in England in 2006. I wish to thank the conference participants for their helpful comments on my papers.

All intellectual work is a process of accumulation. Four individuals, in particular, stand out for me for the way in which their intellectual generosity contributed to my work. I am indebted to Jean C. Robinson, Amy G. Mazur, Rachel G. Fuchs, and Karen Offen, who are also my role models. None of whom, of course, should be held in any way responsible for the results.

are revised versions of previously published articles. Secondary Citizens appeared in Simone de Beauvoir Studies 24 (20072008): 3248 as Pretty Pictures: Beauvoirs Feminist Critique of French Consumer Culture in The Second Sex and Les Belles Images (reprinted by permission). Citizen Consumers first appeared in Contemporary French Civilization 34, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2010): 4172 as Fashioning Female Citizens: Popular Womens Magazines and Reproductive Rights in Fifth Republic France (reprinted by permission). I wish to thank the editors of both journals for their aid and support.

At the University of Illinois Press, my editor, Joan Catapano, was an advocate from the beginning, and her patience with and understanding of what proved to be a complex process are truly appreciated. I also wish to thank Tad Ringo, Jane Lyle, and Katherine Jensen for their extra-ordinary assistance.

I also wish to thank my family, Ulla and Hermann Reineke, Ulli Reineke, Susan Quinlan, Terry and Carolyn Quinlan, Erin Quinlan, Derek Peacock, and Deborah and Tom Boza, as well as my friends on two continents, Heike Kreutzberg, Jan and Steffi Bensien, Pascal Gramain, Samir Boukhris, Meredith and Steven Toth, Anne-Marie Fulfer and Sunil Ramalingam, Kim Shaw and Lucas Rate, Deb Stenkamp and Charles Swift, Amanda and Ben Barton, Jessica Ting, Karen Marsh, Tanya Volk, and Kim Windsor for their interest in this project, their support, and their help throughout the years.

Most of all, I wish to thank my husband, Sean M. Quinlan, without whose love, patience, and intellectual feedback I would not have been able to complete this project. Only he knows what I owe him. I am dedicating this book to our two beautiful children, Julien and Adrien, who are a daily source of happiness to us. No words can express our love for them. We hope that they will grow up to live in a world of freedom and gender equality.

INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK EXAMINES a perennial political question: Are women citizens, and if so, how can they speak and act together politically? Recent research in the area of gender and politics has started to shed light on the questions of when and how women participate in political terms. However, studies in the area of democratic theory and citizenship rights have only begun to address the central question of how citizens make themselves into political agents. Arguably, we can better understand how women participate in the political realm by understanding how female citizenswho are traditionally marginalized from the public and political lifeattempt to construct a collective political consciousness or identity that can serve as a springboard for political activism (Childs and Krook 2006; Henderson and Jeydel 2007; see also the section Recent Scholarship below).

My study contributes to this important area of research by examining how, in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, French women used reading and writing about womens sexuality and reproductive rights as a vehicle to promote the idea of communities of women, characterized by a collective feminine identity and likely common political interests. As I shall argue, for second-wave womens rights activists in France and elsewhere, the idea of womens communality held great potential for womens political agency in various areas of public policy, including state laws governing reproductive rights.

In this way, this book presents a case study to show how women can come together to create an imagined sisterhood (Werbner 1999, 223) so that they can speak and act together in the political realm. I am borrowing from Pnina Werbners pioneering study on the feminist collective imagination, and applying it to a specific place and time: postwar France. For the purposes of this study, this period spans the years from 1944, when French women first acquired the right to vote, to 1993, when the French state made hindering a woman from obtaining access to abortion a crime, and which includes 1970, the year the French womens liberation movement, the Mouvement de la libration de la femme (MLF), was born. (The name was later changed by the activists to Mouvement de libration des femmes as they signed pamphlets and publications.)

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.