A solid and well-documented investigation into the Womens Liberation Movement in France: its actions, its components, its relations with previous generations, and its painful internal conflicts. It reveals the very important role played by radical and materialist feminists. It is an effective antidote against the invention of French feminism by some American scholars.

Sylvie Chaperon, professor of contemporary and gender history at the University of Toulouse Jean Jaurs, Laboratory FRAMESPA

Finally! In Lisa Greenwalds remarkable book on the history of French feminism after World War II, she restores overlooked feminist activists of the 1950s and 1960s to their rightful place.

Sarah Fishman, associate dean for undergraduate studies, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Houston

Lisa Greenwald introduces anglophone audiences to the breadth and depth of Second Wave feminism in France. Her bold analysis encompasses much more than theory by restoring to us the complexity of the activist components of the Mouvement de Libration des Femmes.

Karen Offen, senior scholar, Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University

Femininity and womanhood had long been expressions of womens power and the root of their identity in French society, writes Lisa Greenwald. Her lively, smart, and thoroughly researched book shows how those termsand the power arrangements and identities they stood forwere revised, reinterpreted, and repudiated.... The fiftieth anniversary of May 68 will direct new attention to its powerful aftershocks. Feminism was one of those aftershocks, and Greenwalds book will be part of our reappraisal of this historical moment.

Judith G. Coffin, associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin

This is the book you need in order to grasp the complex history of French Second Wave Feminism.

Bibia Pavard, senior lecturer in history, Center for Interdisciplinary Research and Analysis of Media ( CARISM ), University Paris II

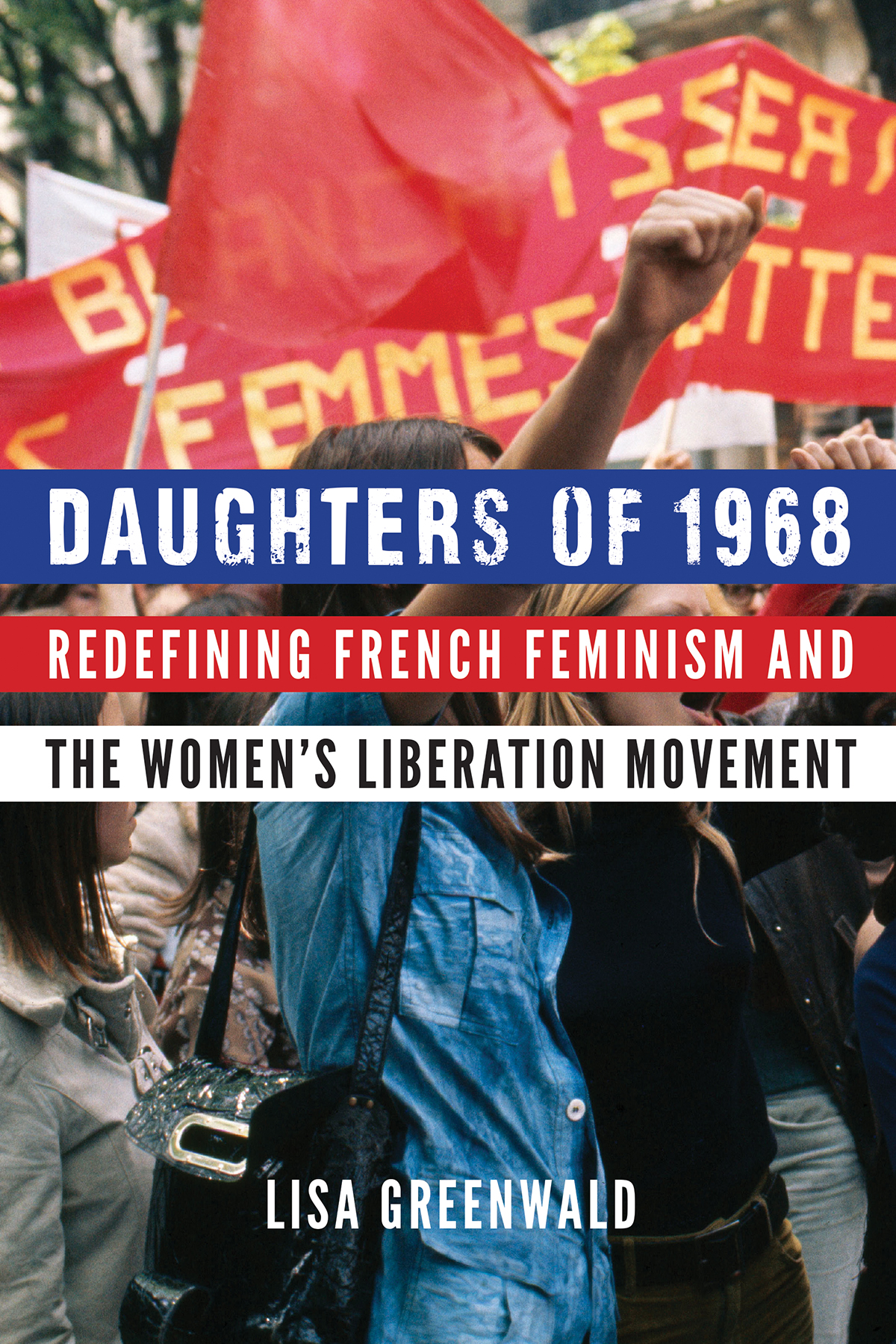

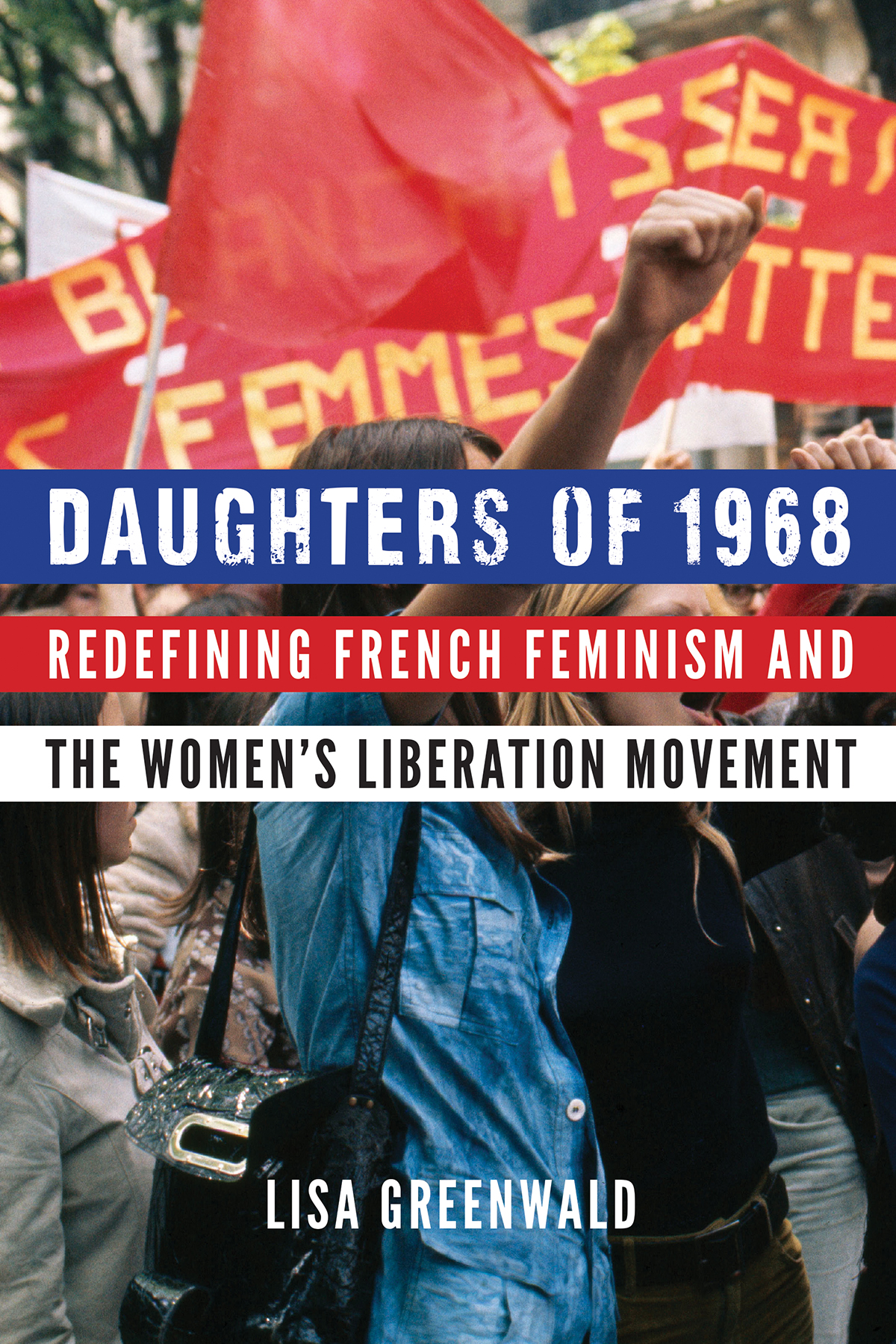

Daughters of 1968

Redefining French Feminism and the Womens Liberation Movement

Lisa Greenwald

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2018 by Lisa Greenwald.

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image Martine Franck / Magnum Photos.

Author photo Lauren Shay Lavin.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Greenwald, Lisa (historian), author.

Title: Daughters of 1968: Redefining French feminism and the womens liberation movement / Lisa Greenwald.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018028387

ISBN 9781496207555 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496212016 (epub)

ISBN 9781496212023 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496212030 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: FeminismFranceHistory20th century. | Womens rightsFranceHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HQ1613 .G685 2018 | DDC 305.420944/0904--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018028387.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

In memory of

B. G.

and

B. F.-G.,

Two mothers who started it all

To emancipate woman is to refuse to confine her to the relations she bears to man, not to deny them to her; let her have her independent existence and she will continue none the less to exist for him also: mutually recognizing each other as subject, each will yet remain for the other an other. The reciprocity of their relations will not do away with the miraclesdesire, possession, love, dream, adventureworked by the division of human beings into two separate categories; and the words that move usgiving, conquering, unitingwill not lose their meaning. On the contrary, when we abolish the slavery of half of humanity, together with the whole system of hypocrisy that it implies, then the division of humanity will reveal its genuine significance and the human couple will find its true form.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

Many of you asked us who we are. We are women. Women who no longer accept:

To be destined from birth to give free domestic labor, seven days a week;

To be educated for this in submissiveness and passivity;

To be refused any professional or vocational training;

To be treated like merchandise on the streets; to be insulted when we dare to consider ourselves as people;

To work for wages that are systematically inferior to those of men, without escaping the tasks of our sacrosanct role at home;

To not even have the right to manage our own bodies and our own lives since the men who rule us impose upon us their laws to perpetuate the species.

We are 27 Million. United, we represent a force capable of radically transforming our situation and imposing the means of our liberation.

Flyer of Mouvement de Libration des Femmes (Womens Liberation Movement)

Contents

This project has been the work of more than two decades and, as such, has benefited from the help of manyscholars, librarians and archivists, friends, editors, the French government, a multiyear Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellowship, historical subjects, and a spouseonly some of whom are mentioned below but to all of whom I owe a large debt. To single out but a few: My first thank-you goes to Sarah Fishman, who never forgot the importance of this project and who pointed me in the right direction, and to my editor Alisa Plant, who embraced the project and has seen it to fruition. As contemporary as this history was when I began, the project would not have been half as rich had it not been for the generous offerings of movement women who ransacked their closets and files for old papers to show me, offered me other contacts, and granted me long interviews.

The following scholars read and commented on this work as it was being developed and went out of their way to do so. For their efforts to help me shape and think through this large project and their sage and detailed critiques, I want to thank Kathryn E. Amdur, Sylvie Chaperon, Judith G. Coffin, Monique Dental, Laura Lee Downs, Judith Ezekiel, Sarah Fishman, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Rachel G. Fuchs, Nancy L. Green, Marie-Victoire Louis, Margaret A. Lourie, Judith A. Miller, Claire Moses, Mary E. Odem, Karen M. Offen, Franoise Picq, Keith Reader, Sandrine Sanos, Bonnie G. Smith, and Danielle Voldman. Many friends and family members encouraged me over the years to make this book a reality and helped me in ways large and small, from advising on translations to offering tea and sympathy; but in particular, I want to thank Laurence Bessac, Linda Blaustein, Sophie Boxer, Peter Cariani, Catherine Cruveilher, Ruth Dickens, Antonella Fabri, Laura Goldin, Vicki Greenwald, Anne-Claire Nguyen Haye, Claudine Jurkovitz, Laurence Lagane, Audrey P. Lavin, Frank Lavin, Maud K. Lavin, Philippe Michaud, Gail Cavat-Negbaur, Michle Perrin, Anne-Christine Potocka, Agns Saint-Raymond, Lynn Sharp, Jamie Stanesa, Lucy Tart, Maris Wacs, and the late Nori Nke Aka, and my late parents, Beverly and Michael Greenwald.

Finishing this book and teaching full-time has not been an easy task, but it has been wonderful to work with colleagues at Stuyvesant High School and so many excellent, curious, and enthusiastic students who remind me every day that robust intellectual discourse is not only the purview of universities. Jennifer Suri and Eric Contreras helped me to be both a full-time teacher and a scholarI could not have done both without their support. James Waller and Martha Ash provided excellent granular editing. Mary V. Dearborn, longtime mentor and friend, encouraged this and many other of my intellectual and professional projects over the decades, for which I am deeply grateful.

Next page