I love this book, all of it. The polished essays and the interviews with birth workers dare to take on the deepest questions of human existence.

Carol Downer, cofounder of the Feminist Womens Heath Centers of California and author of A Womans Book of Choices

This volume provides theoretically rich, practical tools for birth workers and other care workers to collectively and effectively fight capitalism and the many intersecting processes of oppression that accompany it. Birth Work as Care Work forcefully and joyfully reminds us that the personal is political, a lesson we need now more than ever.

Adrienne Pine, author of Working Hard, Drinking Hard: On Violence and Survival in Honduras

This book places the doulaas a caring birth activistat the heart of reproductive care work in our modern society. Doula, a new name for an ancient traditional role, reappears today as women daring to reclaim their power through birthing and caring for their children.

Valrie Dupin, cofounder and cochair of the Association Doulas de France

All we are doing in this world is living and dying, creating and destroying. We generate new life in our children and in our ideas. Becoming a birth supporter, getting to be an attendant to the miracle of childbirth, has transformed my social justice work. Our visions for justice are what we are birthing in this world. Learning to listen, learning to trust the body and the people, and learning to breathe will transform our movement work. Birth Work as Care Work demonstrates these lessons through showing us ways we can learn together to support the birth of new worlds.

Adrienne Brown, coeditor of Octavias Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements

Alana Apfel is an artist and a robust one. Weaving the logic behind birth, care, and reproduction together, Birth Work as Care Work documents how caregivers and communities are marginalized in society on a daily basis whilst working to sustain themselves and ironically, to sustain life itself. Her thesis seeks to put the human back into being.

Chitra Subramaniam, editor in chief of The News Minute

Alana Apfels nuanced Birth Work as Care Work moves us away from a choice narrative to an understanding of the need for justice based on a politics of care work. The book will be a necessary movement builder because of the honesty and complexity of the wisdom spoken.

Susan M. Reverby, professor of Womens and Gender Studies, Wellesley College

Against an infinity of individualizing self-help books on birth and mothering, this anthology outlines a politics of birth through multiple voices. Birth is a central moment in the lives of collectives, involving a variety of participants and possibilities for change. Breaking with the invisibility and undervaluing of the reproductive sphere, this book shows what collective life and social movements can learn from birth in relation to labour, care work, community, and mothering.

Manuela Zechner, the Nanopolitics Group

Whether in the hospital, at home, or in the jail, doulas lovingly support the mom throughout the entire experience and into the postpartum period. Birth Work as Care Work powerfully demonstrates this through testimonies of birth experiences and in discussion of diverse aspects of the work. A must read.

Maddy Oden, doula and executive director of the Tatia Oden French Memorial Foundation

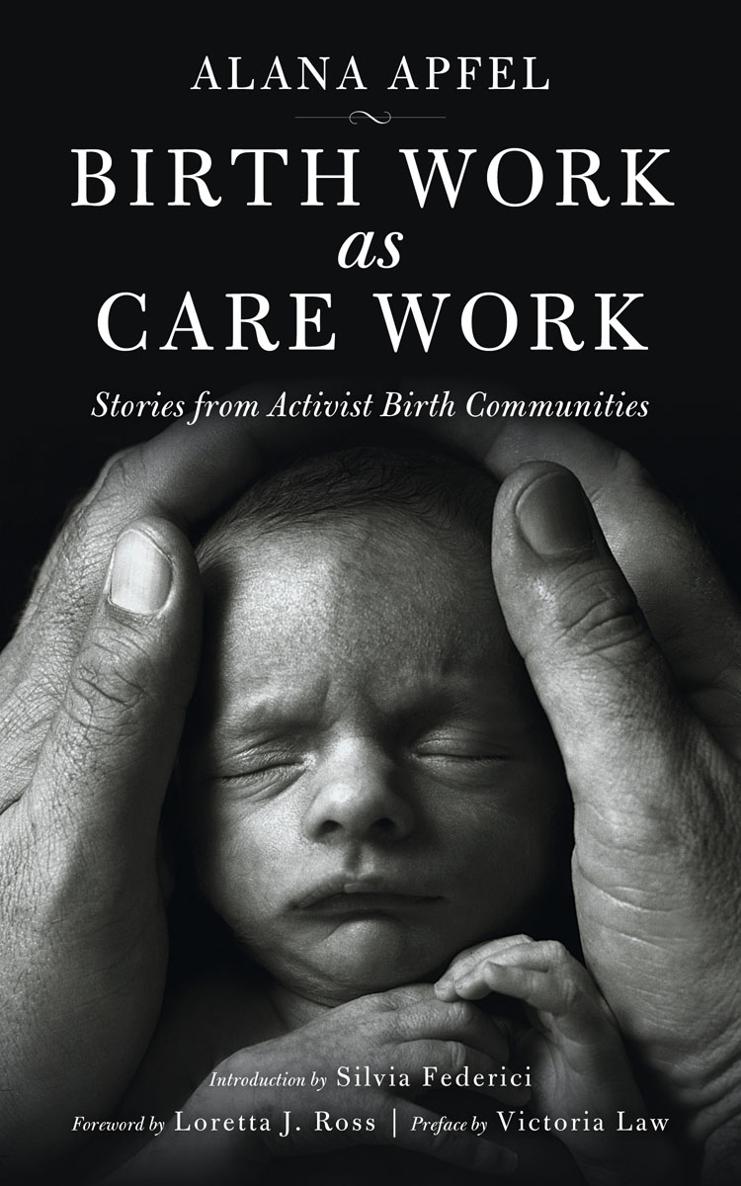

Birth Work as Care Work: Stories from Activist Birth Communities

Alana Apfel

2016 PM Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 9781629631516

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930964

Cover by John Yates / www.stealworks.com

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan.

www.thomsonshore.com

Acknowledgments

This book was made possible through the support and contribution of many incredible people. Thank you to my teacher and friend Andrej Grubai for putting an early version of this book forward for publication. Thank you to everyone from PM Press who helped make this happen: Ramsey Kanaan, Romy Ruukel, Gregory Nipper, John Yates, Jonathan Rowland, Steven Stothard, and Camille Barbagallo, and to Brian Layng for the beautiful design work. Thank you to Loretta Ross, Silvia Federici, and Victoria Law for writing introductions to the book. What you have collectively brought to feminism and to liberatory political projects throughout the world is truly legendary. I am honored to collaborate with you all. A huge thank you to all the contributors who shared their story with me in interviews: Jodi Koumouitzes-Douvia, Kelly Gray, Laili Falatoonzadeh, Cynthea Denise, Yania Escobar, Molly Arthur, Jewel Buchanan-Boone, and Sophia Perez. Your collective dedication to birth and Reproductive Justice is unfailing and an inspiration for all involved in this struggle. A special thank you to Grace Saras, Joanna Morrison, Donae Snow, and Marina Cochran-Keith, whose births inspired the doula stories included in this book. You are warriors. Never forget it. Lastly, thank you to my father, Franklin Apfel, for your unwavering support, endless Skype conversations, and that dance move.

Foreword

Loretta J. Ross

I was terribly afraid to begin this piece on birth work. It took me a while to figure out why. My experience with birthing was probably the primary reason. I remember the trauma of my birthing experience when I was fifteen. I was pregnant because of incest, rape by a married cousin twelve years older than me. I had no choice about whether to have the baby because abortion was illegal and largely inaccessible in the 1960s. My mother stuck me in a home for unwed pregnant girls to hide me from the community. We jointly planned to give the baby up for adoption. The home was run by the Salvation Army, whose workers offered a bizarre combination of compassion and religious zealotry that blamed our pregnancies on our alleged immorality and our failure to sufficiently believe in Jesus. There was no space to talk about incest, child sexual abuse, or even the progress of our pregnancies in this setting. We woke up early every day to pray, clean the buildings, listen inattentively to a school tutor, and count the painfully slow minutes until we were liberated from this pseudo-prison by the labor pains of birth. For me, going into labor signaled liberation from confinement, returning to my family, and forgetting the horror of the entire pregnancy. It did not mean becoming a mother, because I had no intention of keeping the child of my rapist.

Until my son was born. The hospital nurses accidentally brought my son to me after his birth. I question whether it was an accident because the hospital policy was that children scheduled to be adopted were not to be brought to their mothers for nursing. Yet, my son was placed on my breast the next morning and all I could say was, Hes got my face hes got my face in wonder as the miracle of mother bonding overwhelmed all of my previous decisions about this little person suckling on me. So I decided to keep my son, and I have coparented with my rapist for the past forty-seven years. I cannot overstate the impact of this decision on me and my son. While I dearly love my child, he has never received from me the unconditional love every child deserves because I had to love him despite the circumstances of his conception and birth. This type of unresolved trauma lingers in my DNA and affects my worldview, my relationships, and my physical being even now.