EDITORS

Sherry B. Ortner, Nicholas B. Dirks, Geoff Eley

A LIST OF TITLES

IN THIS SERIES APPEARS

AT THE BACK OF

THE BOOK

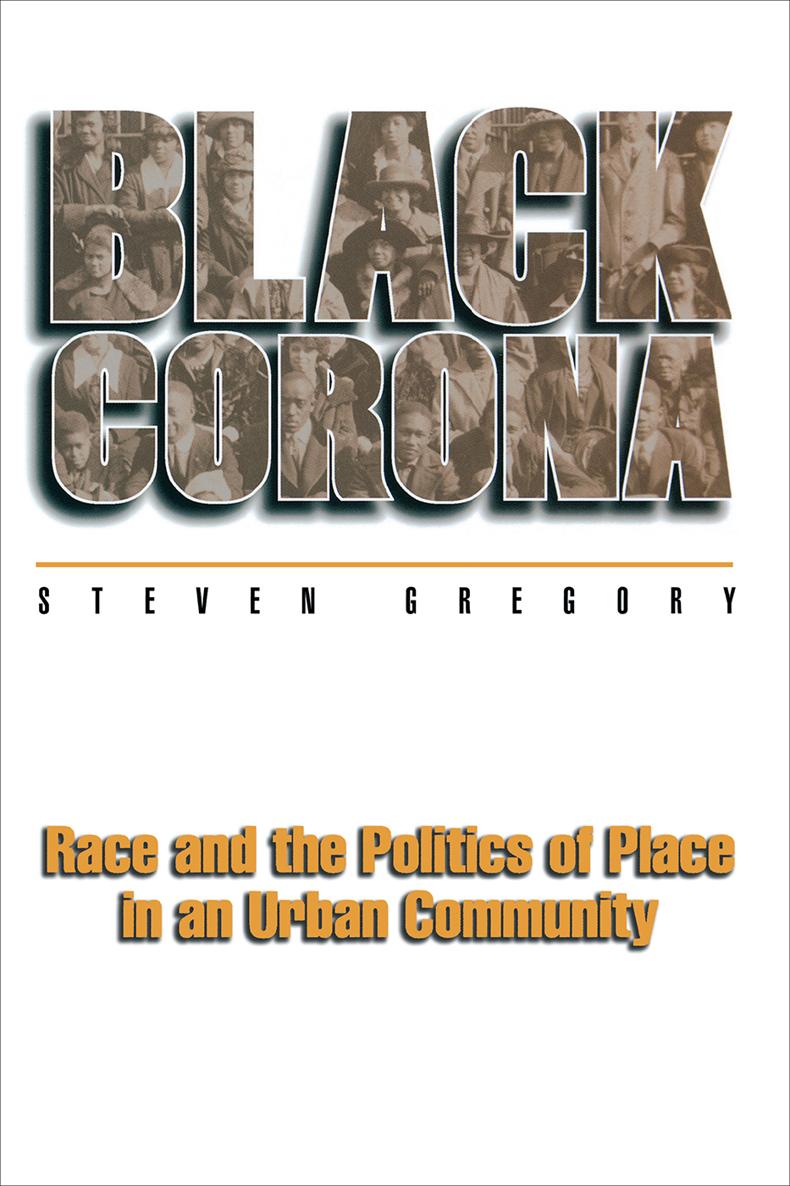

BLACK CORONA

RACE AND THE POLITICS OF PLACE

IN AN URBAN COMMUNITY

Steven Gregory

Copyright 1998 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gregory, Steven

Black Corona: race and the politics of place in an

urban community / Steven Gregory.

p. cm. (Princeton studies in culture/power/history)

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 0-691-01739-5 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Corona (New York, N.Y.)Race relations. 2. New York (N.Y.)

Race relations. 3. Afro-AmericansNew York (State)

New YorkPolitics and government. 4. Urban ecology

New York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 5. Political

cultureNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century.

I. Title. II. Series.

F128.68.C65G74 1998

306.20899607307471dc21 97-39537 CIP

This book has been composed in Times Roman

Princeton University Press books are printed

on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines

for permanence and durability of the Committee

on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity

of the Council on Library Resources

http://pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

TO THE MEMORY OF MY FATHER

Raymond Edward Gregory

Contents

Chapter One

Introduction

Chapter Two

Making Community

Chapter Three

The Movement

Chapter Four

The State and the War on Politics

Chapter Five

Race and the Politics of Place

Chapter Six

A Piece of the Rock

Chapter Seven

Up Against the Authority

Chapter Eight

The Politics of Hearing and Telling

Chapter Nine

Conclusion

List of Illustrations

MAP

Research area, North Corona and East Elmhurst, in relation to nearby Queens neighborhoods.

FIGURES

Schoolchildren crossing the Long Island Expressway on their return home to Lefrak City. (Photo by the author)

Lefrak City teenagers speak out at the Concerned Community Adults Youth Forum. (Photo by the author)

Jonathan Bates, chair of the Youth Forum, and Edna Baskin listen to complaints about police harassment. (Photo by the author)

Edna Baskin poses with members of the cleanup team and Leo the Greek, a local merchant. (Photo by the author)

Arthur Hayes, president of the East ElmhurstCorona Civic Association, during neighborhood inspection. (Photo by the author)

Fashion show held during the Ericsson Street Block Associations annual block party in East Elmhurst. (Photo by the author)

Calvin Wynter and John Bell of SAVE oversee final preparations for the reception of Queens College dean Hayward Burns at the Corona Congregational Church. (Photo by the author)

Edward J. OSullivan, director of the Port Authoritys airport access program, poses with a model of the AGT light rail train. (Daily News LP Photo)

Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney responds to audience questions about immigration reform at the United Community Civic Associations town hall meeting. (Photo by the author)

City Councilwoman Helen Marshall discusses election returns with campaign workers at the Frederick Douglass Democratic Association on election night, 1994. (Photo by the author)

Arthur Hayes presents John Bell with the East ElmhurstCorona Civic Associations Pioneer Award for lifelong community service at the associations 1995 Scholarship Dinner Dance. (Photo by the author)

Acknowledgments

O NE SUMMER in the early 1970s, when I was seventeen, my father and I drove down to Richmond, Virginia, from our home in Brooklyn. I had never been further south than Washington, D.C., and I was both intrigued and apprehensive about visiting the place where he had been raised. My father hated the South. He never spoke to me about itabout living under Jim Crow, about the Depression, or about leaving for Harlem in the 1930s with his ten brothers and sisters. Had it not been for the fact that my grandfather and a few relatives still lived there, he probably never would have returned.

Every now and then something would slip out. Once he told me how, during the Depression, he and his brothers would hop freight trains passing through Richmonds black belt and throw coal down to people waiting along the tracks. More often, I would overhear these things at family gatherings or hear them secondhand from my mother. Once she explained to me that my father hated avocados because their texture reminded him of the lard that his family used to make sandwiches during the Depression. But never, ever did he speak to me about segregation or about his experiences with racism in the South.

To be sure, he was not a very talkative man when it came to his own life. Nor was he very political, at least in the ways in which I then thought about politics. (I was a high school militant at the time and dismissed anything short of armed insurrection as reactionary.) My father practiced his beliefs with a quiet and unembellished determination, not uncommon for his generation: one that had lived the mundane details of life as potentially deadly encounters with American racism. In fact, I only recently remembered the morning in 1963 when my father left for the March on Washington, a suitcase in one hand and a Stetson hat in the other; he had left quietly and without a fuss.

When we got to Richmond, my father took me on a tour of the city, which seemed a bit curious given his usual lack of interest in sightseeing anywhere. He took me first to the area of the city where he had lived and that had since become Interstate 95. For thirty minutes we stood by the highway, cars barreling by, as he perused the few surviving landmarks. We used to live over there somewhere, he said, frowning and pointing to a spot in the northbound, center lane. Mustve been somewhere over there, near that overpass.

Next, we took a bus downtown. I used to like sitting in the back of the busin the last row next to the window, where you could see everything happening up front. I had just started down the aisle when my father bellowed after me in a tone that was at once angry, impatient, and perplexed. Why you goin all the way back there? Come sit up here. Frowning, he pointed to a row of seats directly behind the driver and then dropped some change in the fare box. Feeling humiliated and put upon, I sat next to him, avoiding eye contact with the gawking passengers. When the bus pulled off, he turned to me. Took us a hundred years to get here, and you wanna sit all the way in the back. An elderly woman sitting across from us smiled and, looking at me, raised her eyebrows as if to say, You listen to what hes telling you, hear? My father nodded to her as they do in the South and then peered out the window to get his bearings.