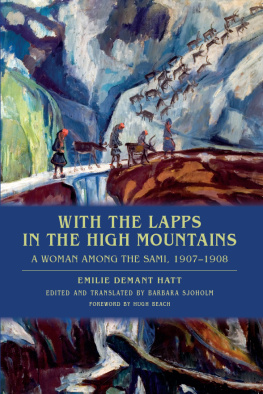

First published in 2004 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1954 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

ISBN 13: 978-1-8452-0010-7 (hbk)

I

INTRODUCTION

This study, sketchy as it is, is based chiefly on lectures and papers delivered on different occasions during the autumn of 1952. , however, are new.

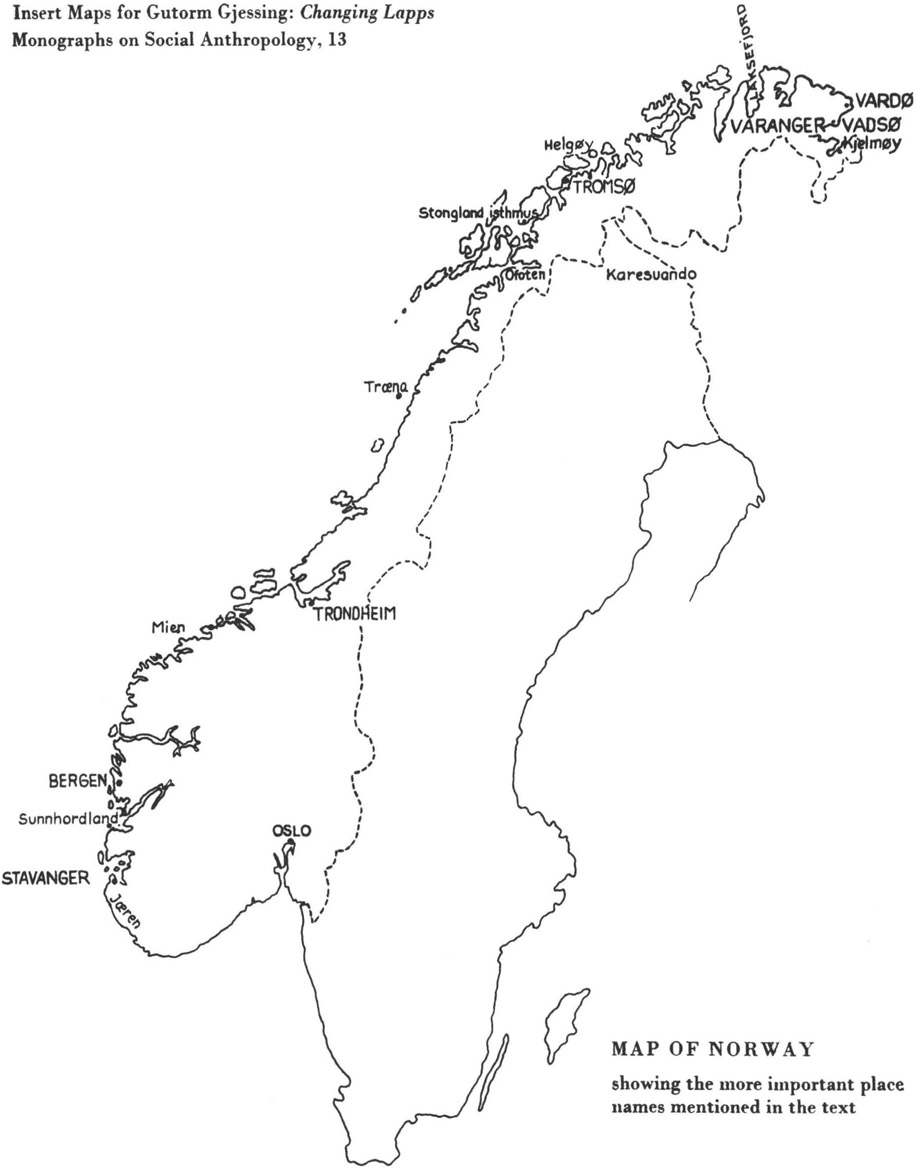

The term Lapp is of Finnish origin, deriving possibly from Lappi , the northernmost wilderness. The word had already been adopted by Swedes as early as the 13th century, and has since become common in international usage. But although it has been current for at least 700 years, it has never been accepted by the people concerned, who have always felt it to be contemptuous. They call themselves Sabme , plural Samek , and several decades ago succeeded in getting this recognised as their official name in Norway (in the form Same , plural Samer ). Norwegian scholars now use it unanimously, and it is also gradually penetrating into Swedish and Finnish literature (e.g. Ernst Manker, Stockholm, uses it sometimes, and Rafael Karsten, Helsingfors, uses it almost consistently). There is, in other words, little reason for preserving the term Lapp in international literature. The explicit wishes expressed with increasing strength by the peoples themselves ought surely to carry much weight. Accordingly, although the term has, for practical reasons, been retained in the title of this study, in the text it will be replaced by Same (pronounced same ), plural Sames , with the adjectival form Samish , in the hope that my friends, the Sames, will succeed in getting their own name recognized internationally.

What has hitherto been published in English about the Sames has been concerned almost entirely with the Swedish reindeer-Sames; this applies also, although it is not explicitly stated, to Prof.Bjrn Collinders book, The Lapps (1949). Joan Newhouses book, Reindeer are Wild too (1952) is an exception, because it deals with the reindeer-Sames from Kautokeino. Miss Newhouse gives a well-written and captivating account of her own stay among the Sames, to be sure; but she does not make any attempt to give a systematic picture of either the culture or the society of the Sames in question. In fact, her book does not seem to have any scientific pretensions; it may, however, be recommended as a supplement to my . T.I. Itkonens recent article in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology (1952) is also an exception in so far as it is concerned with Finnish Sames.

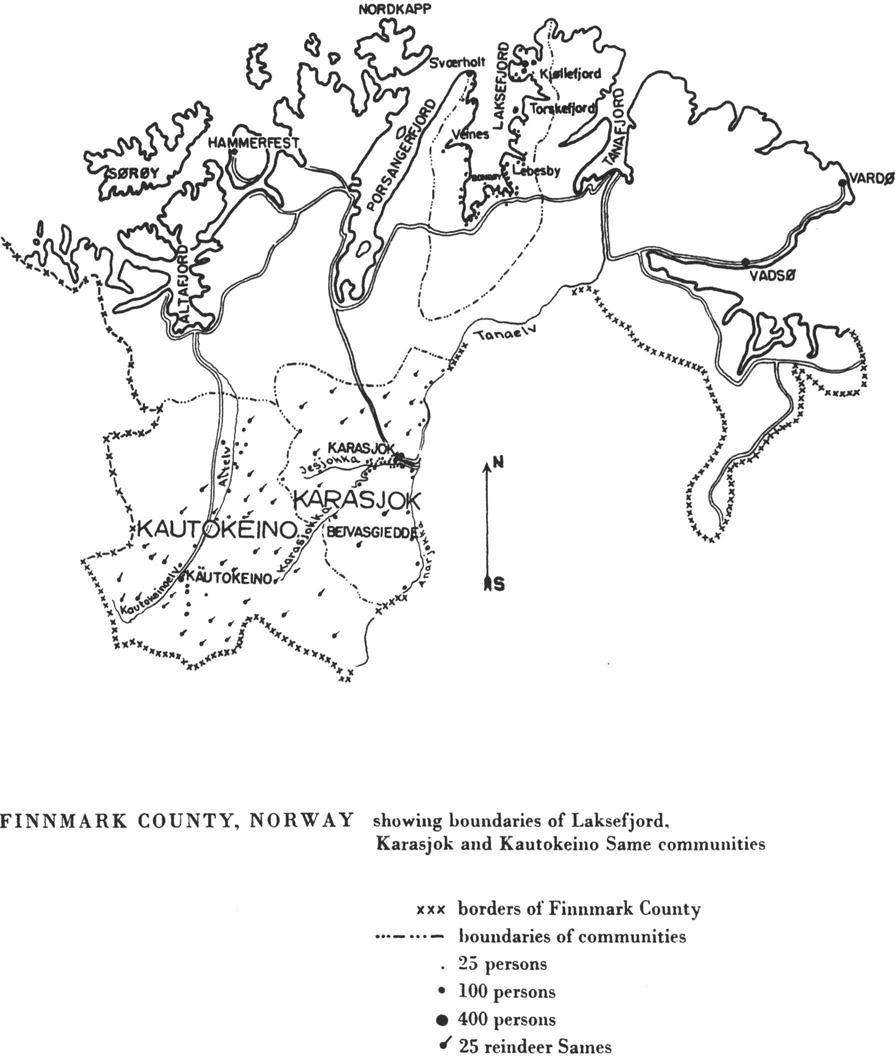

The literature, in any event, gives the impression of a more or less homogeneous Same culture. This is, however, very far from the truth. The Same language is split up into a series of dialects, some of which are so different that they are not even mutually intelligible; for example, Sames from Rlos, on the central Norwegian mountain plateau to the south, and from Finnmark must communicate with one another in Norwegian, Moreover the reindeer-Sames, so strongly predominating in the literature, represent as a matter of fact a relatively small minority. Of definitely more than 20,000 Norwegian Sames only about 1400 have reindeer activities as their economic basis, the rest being mainly sea-Sames and permanently settled inland-Sames. In Sweden, to be sure, the percentage of reindeer-Sames is much higher, but even there the mountain-Sames do not amount to more than about 3,000 in a total number of about 8,500 Sames (1940). To this number can, in certain respects, be added 700 reindeer-breeding forest-Sames who combine reindeer activities with cultivation (Manker, 1947). In Finland and the Soviet Union, too, the reindeer-breeding Sames form only small minorities.

In this study we shall only be concerned with some of the Norwegian Sames, but, even generally speaking, it can at once be stated that the popular and stereotyped picture of the Sames as being almost entirely nomadic reindeer breeders is an essentially false picture.

The vast majority of Norwegian Sames are sea-Sames living along the coasts and particularly in the inner parts of the fiords of Troms and Finnmark. Their livelihood is fishing combined with agriculture, mainly stock-farming. Furthermore there are possibly some 3,000 permanently settled Sames along the main rivers in the interior of Finnmark, now living chiefly on stock-farming. There are also some other variants of minor importance, with which we need not be concerned here. Apart from the accounts of early travellers, such as for example Arthur de Capell Brookes important - and fascinating - books from the 1820s, a short paper by Dr. Asbjrn Nesheim (1949) is the only published work in English on the sea-Sames. The paper consists of an old sea-Sames narration of life in Repparfjord, West Finnmark, in earlier times. As far as the permanently settled inland-Sames are concerned, nothing has, to my knowledge, as yet been published in English.

Although the situation is now changing, it is also of some importance that Same studies have been strongly dominated by philologists. Tis has even been the case with ethnographic and ethnological studies. The consequence is that several problems of interest to anthropology have been neglected or dealt with in a purely historical, reconstructive way. This is particularly true of the problems of Same social structure and the functional aspects of the contact between Samish and Scandinavian cultures. Thus in the book (noted above) by Professor Collinder, the word siid , the local social unit of the reindeer-breeding Sames, is not even mentioned. Of course, there are exceptions (Bergsland, 1942), but it is significant that the only comprehensive studies of sociological problems so far have been made by a jurist (Solem, Lappiske rettsstudier ) and a geologist and human geographer (Tanner, Skoltlapparna ). Thanks not least to the keen interest in Same studies taken by Dr. Ethel J.Lindgren (Cambridge), the situation is now changing, for British and American anthropologists have during recent years done fieldwork among both reindeer-Sames and sea-Sames, emphasizing relevant social anthropological problems. These studies, however, are as yet unpublished, apart from a short article by R.N. Pehrson ( Man , 1950) and one by Ian R.Whitaker and Pehrson (1952), the latter dealing with a very special problem. These authors, however, have been working among reindeer-Sames in Karesuando (Sweden). On the initiative of Dr. Lindgren, the Royal Anthropological Institute has published, in its Journal , a series of articles on Same research in Sweden and Norway (Finland is supposed to follow), written by Scandinavian scholars. From Sweden, only the article on ethnological research work, written by Dr. Ernst hanker has as yet been published, whilst the Norwegian articles deal with linguistics, folklore, and ethnology, written by Professors Knut Bergsland, Reider Th. Christiansen, and myself respectively. These articles, including comprehensive bibliographies, will probably prove useful to students of Same language and culture, from both Scandinavia and abroad, and in view of their existence I have here thought it sufficient to give but a select bibliography.