Published by the ARCTIC STUDIES CENTER

Department of Anthropology

National Museum of Natural History

Smithsonian Institution

P.O. Box 37012, M RC 112

Washington, D.C. 20013-7012

www.mnh.si.edu/arctic

In cooperation with

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SCHOLARLY PRESS

P.O. Box 37012, MRC 957

Washington, D.C. 20013-7012

www.scholarlypress.si.edu

Copyright 2010 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

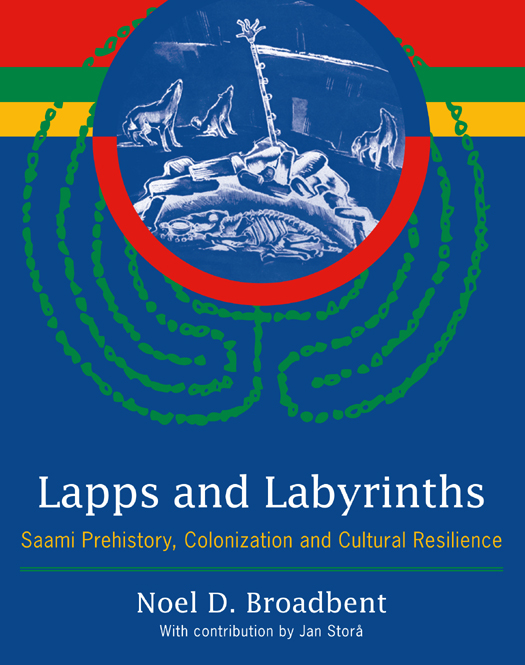

Cover image: A painting of a bear burial marked by an antler-sheathed Saami spear. Ossian Elgstrm, 1930 (Norrbotten Museum). Colors used on cover inspired by the Saami flag.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Broadbent, Noel.

Lapps and labyrinths : Saami prehistory, colonization and cultural resilience / Noel D. Broadbent; with contribution by Jan Stor.

p. cm.

Published by Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution in cooperation with Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-9788460-6-0 (paperback : alk. paper) 1. Sami (European people)SwedenHistory. 2. Sami (European people)SwedenAntiquities. 3. Coastal archaeologySweden. 4. SwedenAntiquities. 5. Antiquities, PrehistoricSweden. I. Arctic Studies Center (National Museum of Natural History). II. Title.

DL641.L35B76 2010

948.50049455dc22 2009028011

ISBN-13: 978-0-9788460-6-0

ISBN-10: 0-9788460-6-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-935623-36-6

v3.1

Contents

DIRECTORS NOTE

William W. Fitzhugh

FOREWORD

Inger Zachrisson

Directors Note

S candinavian archaeology has a long and revered history leading back to the foundation of scientific archaeology pioneered by Christian Thomson, a Dane who devised the three-age classification system (Stone, Bronze, Iron Ages) and Oscar Montelius, a Swede who first developed the seriation method of relative dating based on style-change through time. In the 1940s Gutorm Gjessing, a Norwegian, was one of the first to begin promoting social interpretation of archaeological remains, a view later developed by Frederik Barth, a Norwegian, by developing the anthropological theory of social boundaries as expressed in visible signaling of material culture, style and design. In Lapps and Labyrinths Noel Broadbent, an American who lived and taught for many years in Sweden, carries this tradition of archaeological innovation into the problematic field of historical ethnicity in this case the social and territorial history of the Swedish Saami.

I visited many of the sites discussed in this book with Noel in 1984, before their significance had become obvious from his excavations of the past decade. Like Noel, I spent many years conducting boulder-field archaeology in a similar subarctic environment, central and northern Labrador. I had found this work exceedingly frustrating because the corrosive nature of subarctic soils and transient nature of the sites resulted in poor artifact preservation and recovery. One was often left with elaborate maps of sites and structures of a people whose culture and identity remained unknown or conjectural. One could easily describe the architectural forms, but determining who they were was frequently elusive. Broadbents careful excavation techniques and ingenious analytical methods have turned the archaeology of boulder-field sites from a confusing conundrum to a coherent picture that overturns a century of conventional archaeological wisdom about Saami origins, settlement systems and adaptation. For the first time the ubiquitous but inscrutable boulder sites lining the raised beaches and terraces of Swedens northern Baltic coast sites have been shown to be the remains not of recent Germanic pioneers but of people who must have been ethnic Saami but Saami living a very different life than known from historical records.

Integrating archaeological finds with an array of anthropological data, place-names, history, religion, geography and ecology, Broadbent has produced a revolutionary new synthesis that indicates a former, long-term Saami occupancy of the North Swedish coast and outlines a model of culture change and acculturation stimulated by the northward advance of Germanic-Swedish farmers and fishermen. Rather then viewing this history as one of ethnic confrontation and geographic and political isolation processes that have characterized Saami relations with the Swedish state during recent centuries and continue today Broadbent reconstructs a Late Medieval period characterized by processes of accommodation, cultural exchange and demographic mixing. Only later did institutionalized nation-state policies begin to exclude Saami rights from traditional coastal territories and resources. In time those policies resulted in the re-definition of Saami ethnicity and identity into the reindeer herder of the upper river valleys, interior lakes and mountain zones where most Saami had lived exclusively since the 1700s.

Noel Broadbents research raises many questions that call for further study. More data are needed from other regions of the Baltic coast; correlations are needed between archaeological remains and Lappish place-names in Sweden south of the study area. Relations between traditional Saami shamanic religion, bear cults and medieval Christian practices need exploring. Coastal and interior archaeological sites need more comparative study. Broadbents work lays out a new paradigm that powerfully calls into question the established version of Swedish and Saami histories as separate and apart; it sets forth a new conception of social history for the North Baltic, and perhaps even the greater North Nordic region, in which the Saami have to be seen as more important players in the history of their respective modern states than previously accorded through history and ethnology.

For these reasons this work should be of interest not only to archaeologists and culture historians of northern regions but to students of anthropology, history, linguistics, political science and native studies. It is a work in the broadest of anthropological tradition and breaks new ground in the application of archaeological and anthropological methods to issues of modern concern. While dealing with the history of a small Saami population in a restricted area of the northwestern Baltic, the historical situation that transpired following the appearance of newcomers in their lands has been experienced by many indigenous peoples around the world. In this sense Broadbents Lapps and Labyrinths has broad application and demonstrates the value of anthropological studies for balancing the dominance of history in native studies. This work is in the best tradition of Scandinavian archaeology and breaks new ground for science and society.

William W. Fitzhugh, Director

Arctic Studies Center

Smithsonian Institution

Foreword

S aami bear burials seem to retain their magic, even today. They are eye-openers, being such explicit expressions of Saami identity. They clearly tell that the Saami were here! This insight gave Noel Broadbent a new direction in his research one that he had not expected. The same befell me in 1970. As the archaeologist in charge at Vsterbotten County Museum in Ume, northern Sweden, I was commissioned to investigate a bone find on an island in Lake Storuman in Lapland. This turned out to be a well-preserved bear burial, not older than 250 years. Up to then I was specialised in the metal techniques of the Scandinavian Viking Age. But just like Noel, I became fascinated by Saami cultural history. A totally new world opened up before me. I still have that fascination, and it surprises me that more Swedish archaeologists have not been affected in the same way. Since then, I have worked with Saami archaeological material and its relationship to Scandinavian culture, initially with material from undisputed Saami areas that is, the inland regions north of the River ngermanlven. But in 1982, I realised that a cemetery from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, much further south at Vivallen in northwestern Hrjedalen (excavated in 1913), must also be Saami nobody was more astonished than myself. Two hearths from the ninth and thirteenth centuries typical of Saami huts were found nearby and we excavated a hut foundation as well as other remains from the eleventh century. This led to an interdisciplinary project of early Saami culture and its relationship to the Scandinavian (Germanic/Nordic) culture in the central part of the Scandinavian Peninsula. This project showed that the Saami had been there at least 2,000 years and had extended south of there to about the 60th parallel. The book