THE CHINESE CONUNDRUM

Engagement or Conflict

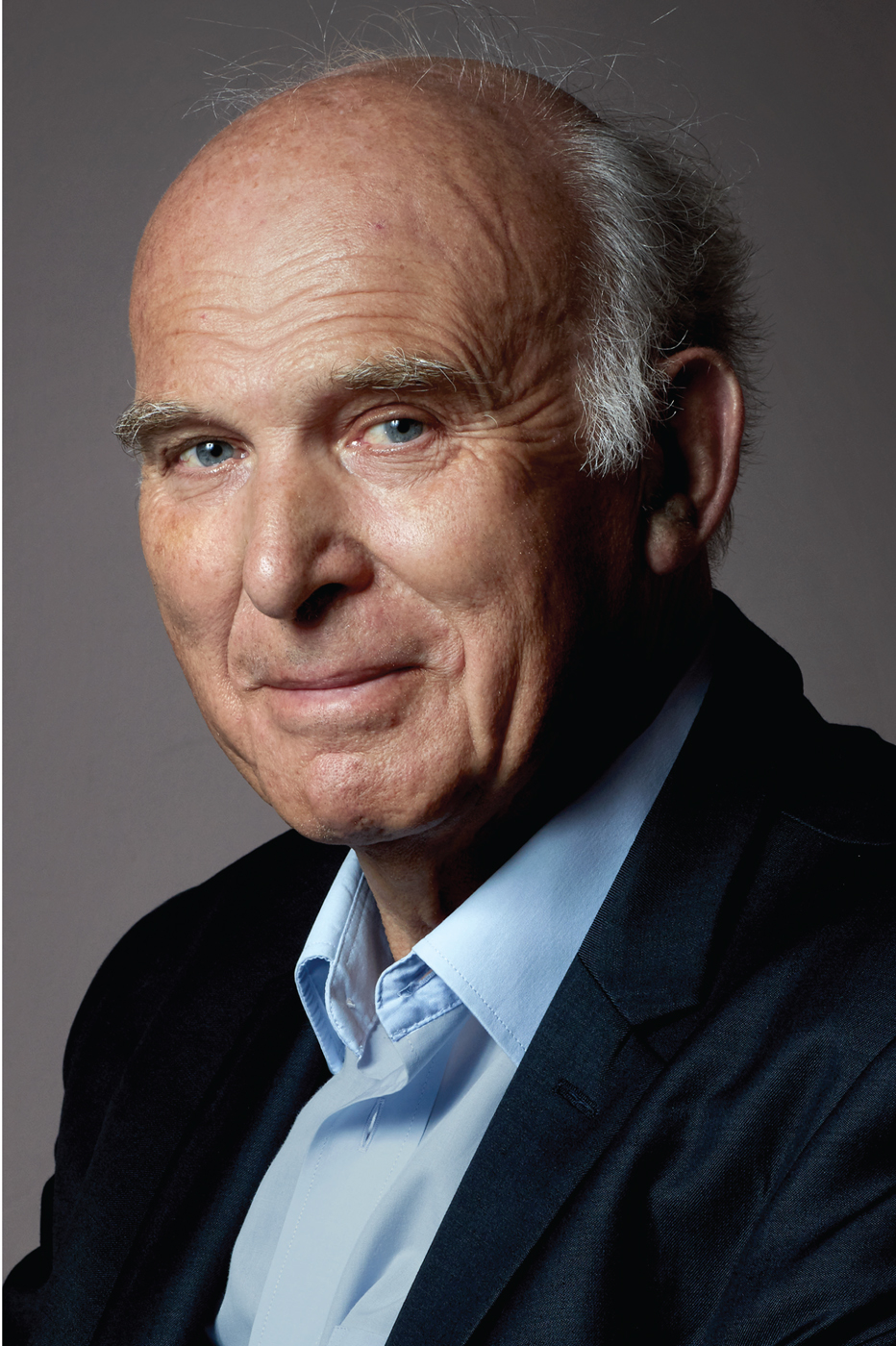

Vince Cable

ALMA BOOKS LTD

Thornton House

Thornton Road

Wimbledon Village

London SW19 4NG

www.almabooks.com

The Chinese Conundrum: Engagement or Conflict first published by Alma Books Limited in 2021

Copyright Vince Cable, 2021

Front-cover image Clive Arrowsmith

Vince Cable asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

ISBN: 978-1-84688-468-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

CONTENTS

The Chinese Conundrum

Engagement or Conflict

Foreword

There is a vast outpouring of books and papers on China. Why would I want to add to it? I am not a China scholar, do not speak or read the Chinese language and have never lived in China. My direct experience is confined to a modest number of business visits over a thirty-year period.

What motivated me to write this book and an earlier, shorter pamphlet (China: Engage! Avoid the New Cold War) was the rapid deterioration in the political climate around Britains relations with China. I was closely involved, in a ministerial capacity, during the early part of the last decade, in what was called the Golden Era of cordial relationships and positive perceptions built around commercial diplomacy.

There is now a growing narrative of China as a threat, reflecting more authoritarian and ideological politics within China and assertiveness externally under President Xi; a more confrontational consensus in the USA over technology, trade and human rights; and, to a degree, home-grown doubts. Recent events, such as those in Hong Kong, have reinforced the negativity. That narrative is, at best, one-sided. I felt that I should assemble and analyse the evidence we have, from commentators and analysts coming from different perspectives.

Getting the balance right is important, since China is already, arguably, an economic superpower alongside the USA, and is likely though not certain to grow in relative economic and political importance. Since Britain, outside the European Union, is now trying to define itself as Global Britain and even as an Asia-Pacific power, it matters that we get the relationship with China right.

My own involvement with China goes back to my membership of Shells scenario-planning team and being invited to carry out scenarios specific to China as part of the challenge process before the company made an irrevocable commitment to large investments in China, especially the Nanhai petrochemicals joint venture in Guangdong province.

This exercise opened my eyes to the extraordinary pace and achievements of Chinese development, but also to its less attractive features (my Shell China counterpart, a young woman with children, was unjustly imprisoned at the behest of an aggrieved commercial party). The project went ahead, is deemed to be a considerable success and has been expanded since. I was left with a great admiration for the Shell scenario process, and make use of it in Chapter 7.

When I spent some time, later, at Chatham House, I embarked upon and published a comparative study of development in China and India, with which I had had more acquaintance.1 It seemed then, and more so now, that the trajectories of these two populous and remarkable countries in terms of economic, politics and environmental stewardship particularly will shape the planets future later this century. I believed then that Indias more gradual, decentralized and democratic approach must win out. Now I am not so sure.

It was my role in the Coalition government, as president of the Board of Trade as well as Secretary of State for BIS, that led me into close involvement with Chinese decision-makers, British firms, universities and others who were trying to do business in China and with Chinese firms investing in the UK. It was one of the top priorities of that government to boost commercial and wider relationships with the big emerging economies: China, India, Brazil and Russia.

All the evidence suggested that the UK was, hitherto, seriously underperforming in comparison to other European countries, especially Germany, and we needed to make a major effort of engagement to catch up. In practical terms, that meant a great deal of travelling to those countries especially China for promotion and negotiation, as well as welcoming their representatives and investors here. On most metrics, the efforts were productive in realizing trade and investment opportunities beneficial to the UK as well as China. That was the Golden Era a phrase which now invites derision.

Short ministerial visits, hobnobbing with the rich and powerful and communicating with officials through translators do not provide the best vantage point for deepening knowledge of a country. The national and provincial officials with whom I had to deal were clever, polished and open to debate and ideas (at least in private), but represented only the governing elite. I was also fortunate to be able to meet, thanks to the British embassy and consulates, some of the brave people speaking up for labour, women and LGBT rights, or victims of environmental and health scandals, who were under surveillance.

I also had to deal with, and encourage, Chinese companies who were interested in the UK. Among them was Huawei, which was to become a serious source of friction later. Since Huawei was engaged in sensitive communications work, I insisted on comprehensive and honest briefings on the security implications. I was categorically assured by people who ought to know that Huawei presented no security risk to the UK that was not being adequately managed. I was and am puzzled by claims made subsequently by Conservative MPs in Parliament that the company was, all along, a security risk. That was the first of a whole series of relationships then regarded by serious and responsible people as innocuous or beneficial, and now deemed to be a threat. It is no coincidence that the idea of China as a threat was growing in the USA during the Trump administration.

It was clear all along that there was a politically unattractive side to the China economic miracle. My Lib Dem colleagues were exercised about human rights, as in Tibet. The Chair of my departmental board the CEO of GSK, a British company that has done well in China was faced with the wrongful imprisonment of one of his senior executives. Getting the balance of engagement and independence right was crucial in dealings with China, as with Britains other major commercial and political partners whose misdeeds are serious, such as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states or Turkey. I fear that that balance is now wrong: hence this book.

In assembling material for the book, I made use as much as possible of the large and growing volume of published material which is, of necessity, from Western (mainly US) sources. I also sought the views of as many UK-based Chinese and China-based expatriates as I was able to contact. From both exercises it was clear that there are wildly different interpretations of what one might regard as matters of fact, like the size of the Chinese economy or the share of the private sector in economic activity, let alone more contentious issues and events. The recent happenings in Hong Kong, for example, widely and independently reported, have produced wholly different narratives from people with no obvious axe to grind.