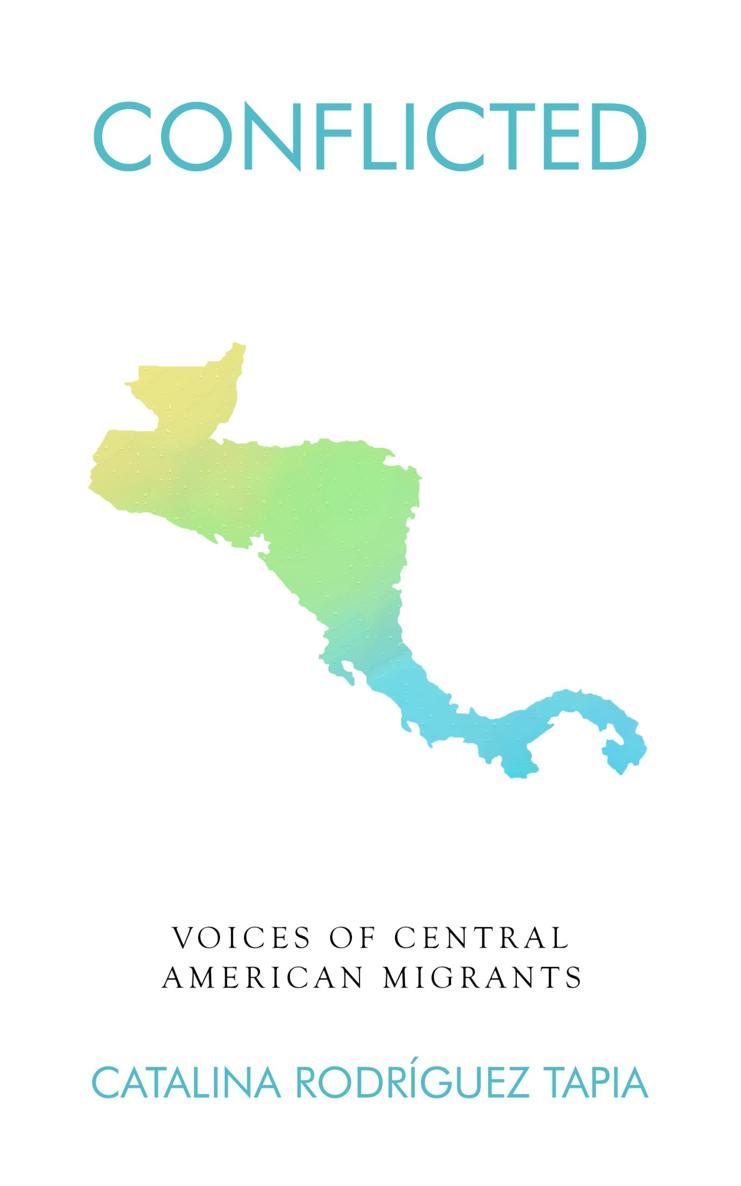

To all those Central Americans living far away from home.

La Amrica Olvidada

Entre el Pacfico y Atlntico

Se encuentra un Istmo descartado

Hundido por aos de negligencia continental

Y distinguido por un son, bien distinto a los dems

En esa Amrica olvidada-

Tierra de los Mayas

Ex concubina de Espaa

Juguete del Norte

Se respir libertad en 1821- y hoy en da se respira dictadura

O resentimiento entre sus maras

La mano dura que machuca y no resuelve

Opresin, la que opaca la voz de la gente

Donde la falta de opciones se resuelve ms all del Ro Grande

Y tras el Ro Grande se respira muerte

Pero en la Amrica olvidada

A veces se respira felicidad-

dos aguas cristalinas que se enlazan en Panam

los tambores garfunas en las Islas de la Baha

que se oyen hasta la ruinas de Copn

Mientras el tico, hablando del ambiente y de la paz

se arrima a Nicaragua, y se encuentra fiesta y bacanal

Y los chapines se revuelcan entre volcanes y ruinas

Con un salvadoreo cuyos sueos no terminan.

introduction

I fanned myself with the stack of questionnaires in my hand and reluctantly made my way toward a stranger. It was a hot summer day in 2015. I was an undergraduate student at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and a long way from home.

I had never been to Columbia Heights before, but it quickly felt like homevendors selling plantain chips (tajaditas, as I would call them), the distinct smell of cheese oozing out of a pupusa that sizzled on a hot skillet in the sidewalk, and the incessant Spanish chatter in accents I quickly recognized were from different Central American countries. In fact, this neighborhood was historically Central American and particularly Salvadoran, since government employees and international agency personnel began sponsoring Central American domestic workers and childcare providers in the 1970s, forming a primarily Salvadoran enclave in Columbia Heights.

That enclave was the reason Id been assigned to this neighborhood and not elsewhere in metropolitan DC. As an intern at the Inter-American Dialogue, a think tank that analyzes Western Hemisphere affairs, my task was to collect data on migration flows, remittance patterns, and political views. This task required me to select strangers at random, ask them invasive questions about their personal lives, and hope they would answer.

Where are you from? Do you send money back home? How much? Id read the questions to my interviewees and write their responses on the questionnaire. The nature of the questions grew increasingly sensitive. Why did you migrate to the United States? And the most invasive question of all, Are you undocumented? Invading the privacy of my fellow Central Americans made me uneasy. But few of these strangers seemed to consider the questions of a twenty-year-old as invasive at all. Rather, many individuals welcomed the opportunity to tell their storyto be heard.

My name is Catalina Rodrguez Tapia. My interest in Central American affairs has been fueled by my experiences and exposure to a region that has always been home to my family. I am a Central American migrant, have family who are Central American migrants, and have parents who are Central American migrants. I was raised in Honduras and lived there for eighteen years, but I am Costa Rican. Now I live in the United States and am not American. When a 1979 revolution brought about unrest in Nicaragua, part of my family was expelled to Costa Rica. Civil war in El Salvador forced one of my mothers best friends to flee with her family in 1980, requiring them to immigrate to Maryland to start a new life.

The stories I explore in this book are not unlike those of my family and friends. Nor are they unlike what I encountered that day in Columbia Heights. That day, I met people from a myriad of backgrounds: naturalized citizens, undocumented migrants, students like myself, workers, people who were thriving, people who were struggling, Salvadorans, Hondurans, Nicaraguans, Guatemalans, and mixes.

Despite these differences among all of them, there was a similarity. They had all left their home of origin in Central America.

The key question is why?

The story of one of the Salvadoran migrants I interviewed left a deep impression. When we met, he was in his late 60s. Back home in El Salvador, he had been a middle-class family man, earning his living as a local store manager. He seemed to have everything going for him at that point, he told me. But then one day, a letter arrived at his place of business, and he knew his life would be forever changed.

In El Salvador, gangs often build their organizations wealth by committing a form of extortion. They call it the impuesto de guerra, which translates to war tax. Gang members impose these fees on businesses, requiring payment in order to avoid casualties. The manwell call him Robertolived and worked in a gang-dominated area. When he received a letter, demanding payment of the impuesto de guerra, Roberto knew the risks it implied. So, he paid it exactly as instructed every monthalways the same amount and always on the due datejust as he paid his other bills. This, he hoped, would keep his family safe.

Before long, the gang increased the impuesto de guerra, and Roberto found a way to raise the funds. But the gang repeatedly increased the fee until, eventually, paying the impuesto de guerra threatened to bankrupt his business. Without other options and without a single doubt in his mind, he packed up and with his family left El Salvador forever.

When I interviewed Roberto on the streets in Columbia Heights, years had passed, and his resolve remained unchanged.

Did I want to leave? he asked rhetorically, Of course not. Thats where I grew up. That was my home. That was my city. But the circumstances were such that it was inevitable. The local police were controlled by the gang members, so I couldnt rely on them. The state had little power in territories governed by the gang members, so I couldnt denounce them to state authorities either. And the prospects of finding another job to pay off the war tax were zero. I did not want to leave. I had to.

Today Roberto is one of the nearly 1.4 million immigrants from El Salvador living in the United States, representing one fifth of El Salvadors population. Similarly, Hondurans in the US comprise approximately 7 percent of its population, and 5 percent of Guatemalas.

Robertos story, like so many others I heard in Columbia Heights that day, echoed the stories Id grown up with in Honduras. Id heard the stories of desperate friends or neighborstheir family members having been kidnapped or even killedforced to flee the country for their safety. Id heard the stories of people who wished to find opportunities elsewhere. And I had my own story: the heartfelt acknowledgement on the day I left Honduras thatdespite my love for the countryI would likely never live there again. We all shared a belief that in another country, although the grass was not completely green, it was greener than at home.