Karin Lorene Zipf - Bad Girls at Samarcand: Sexuality and Sterilization in a Southern Juvenile Reformatory

Here you can read online Karin Lorene Zipf - Bad Girls at Samarcand: Sexuality and Sterilization in a Southern Juvenile Reformatory full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: LSU Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Bad Girls at Samarcand: Sexuality and Sterilization in a Southern Juvenile Reformatory

- Author:

- Publisher:LSU Press

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Bad Girls at Samarcand: Sexuality and Sterilization in a Southern Juvenile Reformatory: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bad Girls at Samarcand: Sexuality and Sterilization in a Southern Juvenile Reformatory" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

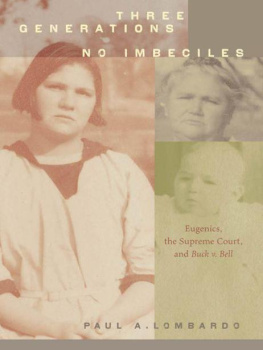

Of the many consequences advanced by the rise of the eugenics movement in the early twentieth century, North Carolina forcibly sterilized more than 2,000 women and girls in between 1929 and 1950. This extreme measure reflects how pseudoscience justified widespread gender, race, and class discrimination in the Jim Crow South.

In Bad Girls at Samarcand Karin L. Zipf dissects a dark episode in North Carolinas eugenics campaign through a detailed study of the State Home and Industrial School in Eagle Springs, referred to as Samarcand Manor, and the schools infamous 1931 arson case. The people and events surrounding both the institution and the court case sparked a public debate about the expectations of white womanhood, the nature of contemporary science and medicine, and the role of the juvenile justice system that resonated throughout the succeeding decades.

Designed to reform and educate unwed poor white girls who were suspected of deviant behavior or victims of sexual abuse, Samarcand Manor allowed for strict disciplinary measures -- including corporal punishment -- in an attempt to instill Victorian ideals of female purity. The harsh treatment fostered a hostile environment and tensions boiled over when several girls set Samarcand on fire, destroying two residence halls. Zipf argues that the subsequent arson trial, which carried the possibility of the death penalty, represented an important turning point in the public characterizations of poor white women; aided by the lobbying efforts of eugenics advocates, the trial helped usher in dramatic policy changes, including the forced sterilization of female juvenile delinquents.

In addition to the interplay between gender ideals and the eugenics movement, Zipf also investigates the girls who were housed at Samarcand and those specifically charged in the 1931 trial. She explores their negotiation of Jazz Age stereotypes, their strategies of resistance, and their relationship with defense attorney Nell Battle Lewis during the trial. The resultant policy changes -- intelligence testing, sterilization, and parole -- are also explored, providing further insight into why these young women preferred prison to reformatories.

A fascinating story that grapples with gender bias, sexuality, science, and the justice system all within the context of the Great Depression--era South, Bad Girls at Samarcand makes a compelling contribution to multiple fields of study.

Karin Lorene Zipf: author's other books

Who wrote Bad Girls at Samarcand: Sexuality and Sterilization in a Southern Juvenile Reformatory? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.