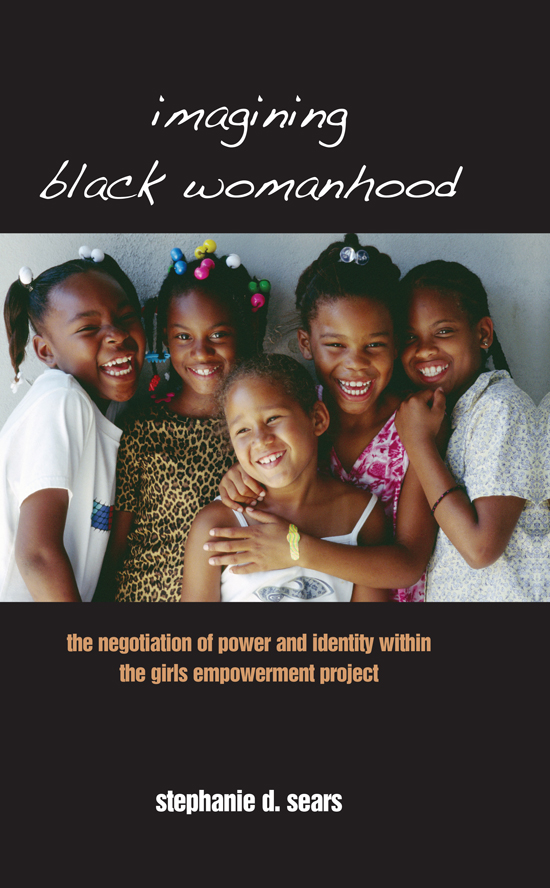

Imagining

Black Womanhood

The Negotiation

of Power and Identity

within the

Girls Empowerment Project

STEPHANIE D. SEARS

Cover photo courtesy of Harry Cutting Photography

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2010 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Diane Ganeles

Marketing by Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sears, Stephanie D., 1964-

Imagining Black womanhood : the negotiation of power and identity within the Girls Empowerment Project / Stephanie D. Sears.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-3327-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4384-3326-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. WomanismUnited States. 2. African American girls. 3. Women, BlackUnited States. 4. Identity (Philosophical concept) I. Title.

HQ1197.S43 2010

305.23089'96073dc22

2009053987

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Figures

Preface

I'm not black, I AM NOT BLACK!

I'll never forget the day Zo, my then three-year-old daughter, defiantly shouted these words. As a special treat we had gone to the neighborhood McDonald's to have lunch and play at the restaurant's play structure. After barely touching her happy meal, Zo was ready to go outside. Quickly taking off her shoes, she raced into the play area. Only one family was there. It was a Chinese mother and her three children (two girls and a boy). The boy was not yet walking, and the girls ranged in age from four to six. As my daughter and the two girls warily negotiated play in the ball pit, I didn't think much of it. My daughter was outgoing, and I had seen her handle similar situations easily.

Soon the sisters climbed into the brightly colored opaque tubes and stationed themselves at the control tower. The control tower was the highest point in the tube structure and contained windows and the only steering wheel. All the children in the tubes had to pass through this center to enter and exit the structure. Tiring of playing alone, it wasn't long before Zo disappeared into the opaque tubes and up to the control tower. My mind began to wander, and Zo's voice drew me back. It sounded as if she said, I'm not fat.

Suddenly she was out of the tubes, crying. Through her tears, she informed me that the girls would not play with her or let her play with the steering wheel. It was near her nap time, so instead of sending her back into the play structure, I thought it best to head home. We started the long process of putting on her shoes and talking about why some children have a hard time sharing and taking turns. But this usually calming approach did not work. Zo did not stop crying. Instead, her tears intensified. Attributing her inconsolable condition to tiredness, I tried to reassure her and hurried up the shoe process.

It was then, with her left arm extended toward me and her right hand pointing to her left arm, that she blurted out: They said I couldn't play with them because I'm black! I'm not black. I AM NOT BLACK! I'm brown. I AM BROWN! She began to cry, a shoulder-shaking, body-trembling cry. I quickly looked for the girls and, most importantly, for their mother. But, sometime in the midst of our conversation, the two girls had exited the tubes and the family had left. It was just my daughter and I, her sobbing and my alternating waves of anger, guilt, sadness, and powerlessness.

My three-year-old daughter had just been introduced to her place within the racialized gender hierarchy, and I had not been able to intervene to protect her to make it right. Zo's age, gender, and race and the fact that she was alone made her appear an easy target for young girls experimenting with their own power. Had an older Black girl or younger White boy climbed into those tubes, I'm certain a different interaction would have occurred and, hence, a different outcome. In other words, though the words had been explicitly racial, the incident commingled race, gender, and age.

As a Black mother, I had always known that this would happen. Mistakenly, I had thought we would not have to tackle these issues until kindergarten. Standing in that playground, mother and daughter became one. We were both Black females and, as a result, despite her incredibly short history and my somewhat extensive experience, had been attacked at our core.

I begin this book at this place because the organization studied herein resembles that McDonald's play structure. Like the tubes, it was constructed as a safe place and contained both visible and hidden spaces for women and girls to flex their own power. Like the incident, oppressive whispers and resistant shouts punctuated the environment. I also begin here because it is from my personal history and experiences as a Black woman, girl, mother, daughter, sister, wife, and friend, as well as my academic training as a sociologist and an African American scholar, that this story is told.

Acknowledgments

An often-quoted African proverb states, It takes a whole village to raise a child. Well, it took a whole village to deliver this book! I owe the completion of this project to many people who knowingly and unknowingly contributed to the intellectual, emotional, and spiritual strength that I relied on during the life of this project. It is with sincere appreciation that I acknowledge those who generously shared their time; offered information; read and commented on drafts; insisted that I continue; insisted that I take a break; walked with me; steamed with me; sat with me; held me; challenged my ideas; listened to my frustrations; and extended love, generosity, and the occasional kick in the pants.

First and foremost, I extend deep gratitude to the women and girls of the Girls Empowerment Project (GEP), whose dreams, fears, and amazing insights are the heart and soul of this project. I know that I have captured only a small portion of your creativity, strength, and wisdom in these pages. You all were the greatest source of inspiration.

I have been blessed with amazing friends and colleagues who supported me in many ways during the various stages of completing this project: Vicki Abadesco, Mary Grace Almandrez, Maxine Leeds Craig, Pam Dunn, Cheryl Finley, Marya Grambs, Breanne Harris; Jumoke Hinton-Hodge, Amy Joseph, Jerusalem Makonnen, Noa Mohablane, Vijaya Nagarajan; Jerry Neale, Pamela Balls-Organista, Dana Pepp, Judy Romero, Joe Sadusky, Joseph Savage, Ronald Sundstrum, Annick Wibben, Shawan Worsley, and the USF Writing Warriors. You all were there when life seemed to push me away from this goal. Thanks for watching the girls, cheering me on, reading drafts, refusing to leave the writing retreat until I finished, transcribing interviews, suggesting books, and just reminding me I could do it. You provided the needed support for me to let go and to let the book have a life of its own.