Table of Contents

The Authors, BirdLife Australia and Charles Darwin University 2021. All rights reserved.

Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO Publishing for all permission requests.

The authors and editors assert their moral rights, including the right to be identified as an author or editor.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

ISBN: 9781486311903 (hbk)

ISBN: 9781486311910 (epdf)

ISBN: 9781486311927 (epub)

How to cite:

Garnett ST, Baker GB (Eds) (2021) The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

Published by:

CSIRO Publishing

Locked Bag 10

Clayton South VIC 3169

Australia

Telephone: +61 3 9545 8400

Email:

Website: www.publish.csiro.au

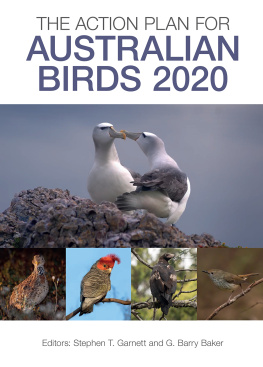

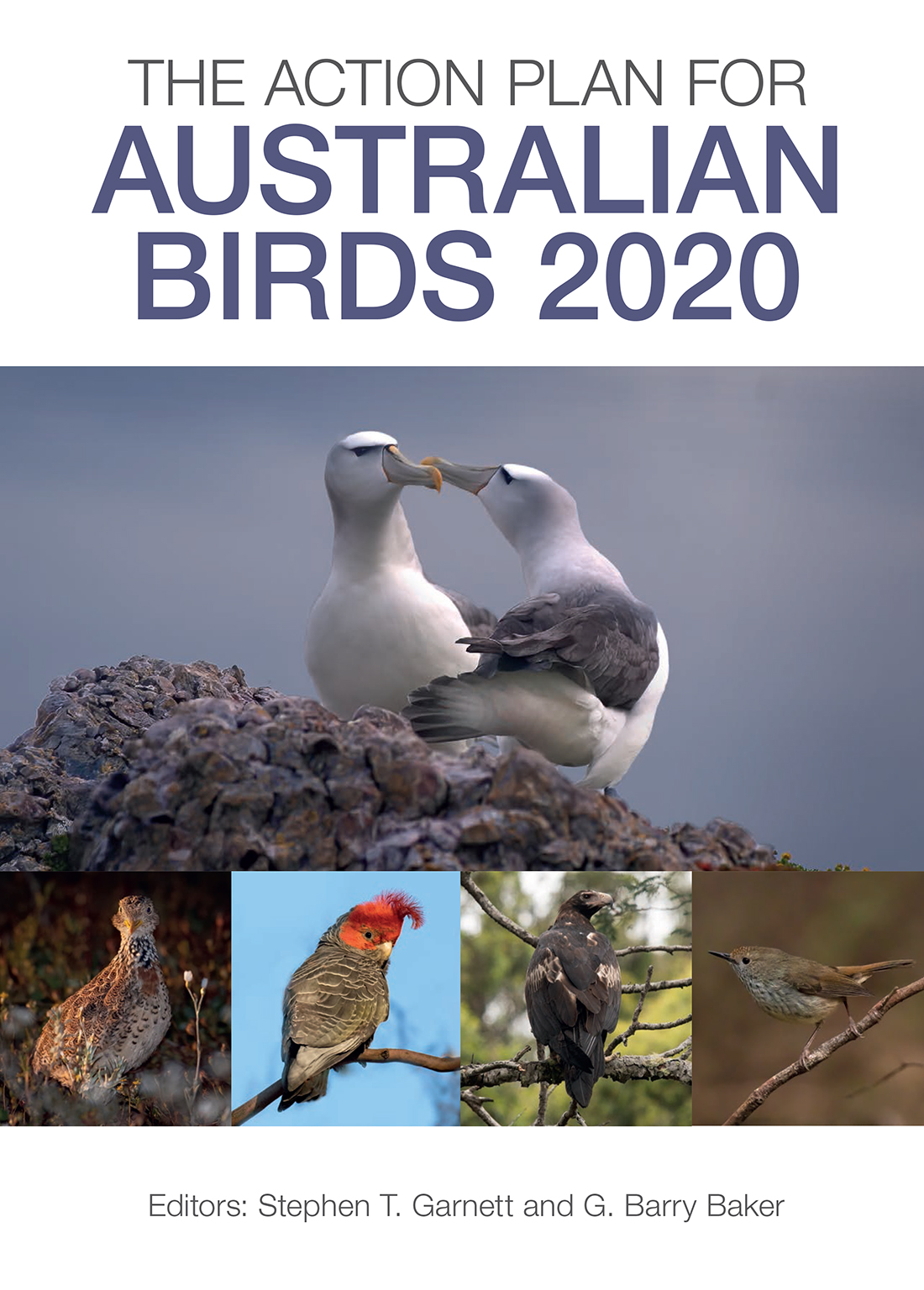

Front cover: (top) A pair of Shy Albatross; (bottom, left to right) Plains-wanderer, Gang-gang Cockatoo, Tasmanian Wedge-tailed Eagle, King Island Brown Thornbill (photos by Barry Baker).

Back cover: (left to right) Forty-spotted Pardalote, Orange-bellied Parrot, Lowland Pilotbird (photos by Barry Baker).

Set in 10/13 Adobe Minion Pro and ITC Stone Sans

Cover design by James Kelly

Typeset by Envisage Information Technology

Printed in China by Leo Paper Products Ltd

CSIRO Publishing publishes and distributes scientific, technical and health science books, magazines and journals from Australia to a worldwide audience and conducts these activities autonomously from the research activities of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of, and should not be attributed to, the publisher or CSIRO. The copyright owner shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information.

Acknowledgement

CSIRO acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the lands that we live and work on across Australia and pays its respect to Elders past and present. CSIRO recognises that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have made and will continue to make extraordinary contributions to all aspects of Australian life including culture, economy and science. CSIRO is committed to reconciliation and demonstrating respect for Indigenous knowledge and science. The use of Western science in this publication should not be interpreted as diminishing the knowledge of plants, animals and environment from Indigenous ecological knowledge systems.

The paper this book is printed on is in accordance with the standards of the Forest Stewardship Council and other controlled material. The FSC promotes environmentally responsible, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the worlds forests.

Jul21_01

Australians have the privilege of living on one of the most biodiverse countries on earth. BirdLife Australia believes we have a moral duty to pass this extraordinary heritage on to our descendants. Our Action Plans for Australian Birds, which we have produced every decade since 1990, are measures of our performance as a society. In them, we assess the risk of extinction of every species and subspecies of bird in our collective care and lay out a course of action to ensure we retain those most at risk.

In reading these texts, it is important to take the long view. Think back, as some of us can, to conservation 50 years ago. The conservation movement was very young. The prevailing philosophy that a loss of nature was an unfortunate but inevitable cost of development was just starting to be challenged. What has happened since has been extraordinary. So many species would have been lost had not the public been willing to invest in their rescue. The ensuing expansion of the reserve system and investment in threat management would have been inconceivable. Rather than an Action Plan for Australian Birds, this would have been a book of the dead, a compendium of species obituaries. That it is not is a testament to the efforts of those who love Australian nature.

Many of the accounts in this book document these successes. Unlike in previous Action Plans, each taxon that is now no longer considered to be at risk is afforded an account to explain why. The very first account describes the quintessential threatened species of the Wet Tropics, the Southern Cassowary. It can no longer be considered threatened. For that, we should be grateful for those who campaigned so successfully for the creation of the Wet Tropics Management Area. Other accounts document the lowering of risk for the many seabirds of Macquarie Island or the efforts made to secure many other species and places for nature.

Thats the good news. For three taxa the White-chested White-eye, the Southern Star Finch and the Mount Lofty Ranges Spotted Quail-thrush there is likely to be no more news. All three were thought to be possibly extinct in 2010. In the last 10 years, that belief has hardened. Two other bird taxa remain in that category the Tiwi Hooded Robin and the Cape Range Rufous Grasswren, last seen in 1994 and 1974, respectively. They join the 22 other Australian bird taxa known only from skins, a few photographs and fading memory.

Another 35 are considered Critically Endangered, up by 10 since the last Action Plan is we exclude all those reassessed on the basis of new information, minor changes to the criteria used for listing and changes to taxonomy. A further 22 are Endangered, up by five, 36 are Vulnerable, up by three, and 22 are Near Threatened, down by seven. The major difference between the Action Plans, however, is not the numbers. Rather it is the nature of the threats. In this Action Plan, the influence of climate change is starting to overwhelm all other threats.

The last decade has seen unprecedented drought, fire and heat such as never been experienced before since records began. And even though all our birds have seen such climates before in their evolutionary history, never has the climate changed so fast. The cassowary may have a lower risk of extinction than in the past, but the same cannot be said for the 20 taxa retreating up tropical mountains. Flinders Chase, set aside for nature a century ago, was a haven until a ferocious fire swept it bare. On top of that, the old threats remain, often adding to the pressure land clearance, invasive species and changes in fire regime.

The next 10 years will determine the fate of these climate challenged species, just as it will determine the fate of our human society. Birds have long warned us of danger. The birds in this book are emblematic of Australian society as a whole. The fate of both needs the same energy and commitment that we have been dedicating to conservation in the last half-century.

Finally, I would like to thank all the research experts, led by Stephen Garnett and Barry Baker, who put the Action Plan together, and to acknowledge all BirdLife Australias conservation partners community and civil society, land managers, governments, zoos, research institutions and many thousands of volunteers who work with us to put the plan into action.