Stories from individual contributors reproduced with permission of the copyright holders.

First published in 2019

Copyright Dr Grinne Cleary 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76029 735 0

eISBN 978 1 76087 081 2

Internal design by Stella and John Danalis/Peripheral Vision

Index by Puddingburn Publishing Services

Internal illustrations by Estee Sarsfield

Set by Post Pre-press Group, Brisbane

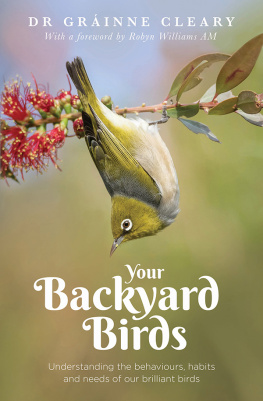

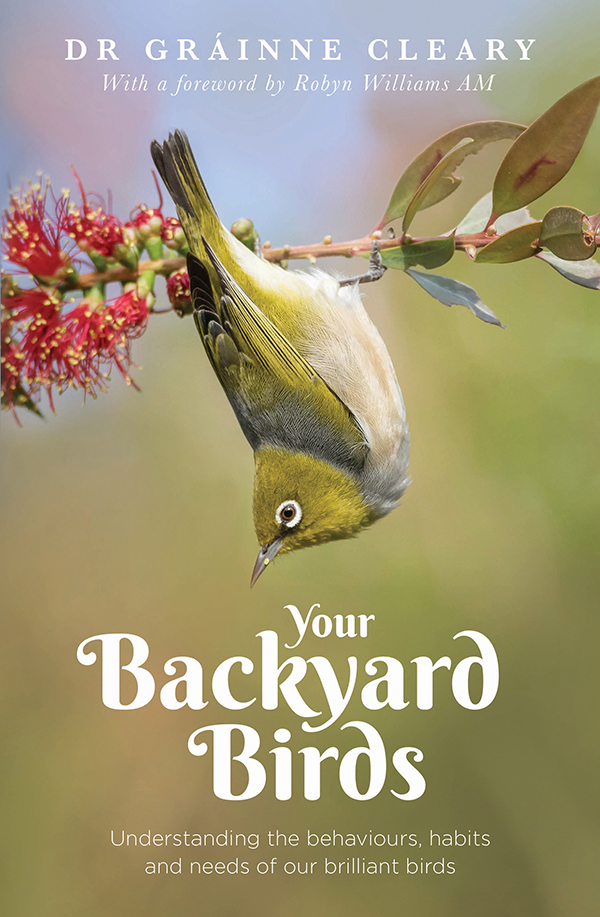

Cover design: Karen Wallis, Taloula Press

Cover image: Pete Evans Photography

Silvereye in Yandina Creek, Queensland

For my hearts best treasure and partner in everything I do, Bill Coleman.

The beat goes on

CONTENTS

I met Robyn Williams while being interviewed by him about bird feeding on ABCs The Science Show. Robyns love for birds shone brightly as he recounted a tale about a cheeky magpie who he had come to know. This magpie would enter his sitting room to land on the coffee table in order to chew on whatever book Robyn was currently reading! I invited Robyn to foreword this book with stories about the birds who share his garden.

I parked the car on the steep drive to our cottage high up overlooking the ocean on the South Coast of New South Wales. Within one minute The Family had turned up on the deck, four magpies, in a row, one of them singing the trills and warbles as distinctive to the Oz ear as the smell of eucalypts to our noses when were overseas.

The Family is two parents, attached to our territory and its surroundings, plus young offspring, still with grey plumage rather than white. They were waiting for meaty snacks from me and I provided them even before unpacking our gear.

We had just returned from Italy and Greece, staying at exquisite locations, but strangely bereft of bird life. Indeed, it was disconcerting when by the Med to see gulls winging past making baby-like noises, yet not looking towards our house, let alone visiting. In Australia, from our cottage, we can see parrots and corvids coming from afar and most of them are heading our way, wheeling and diving, then landing smartly on our deck where lunch is always offered. After our maggies were served, a butcherbird arrives, waiting confidently. I throw a piece of fat towards him and, knowing the game, he zooms upwards, catches the morsel and flicks off into the bushes to devour it. Then back for more. Such an acrobat!

It was windy that day, but crystal clear, with pale blue sky and hardly a cloud. The dishes we have for the birds are wide and solid, the ones usually used under very big flower pots. Several birds can perch on the rims and share. Rain had obviously been scarce, so I put water out and was rewarded immediately with a customer. Why is it so satisfying to see a bird like a magpie dipping its beak in the drink, raising its head to let the water run down its throat, and then to swallow?

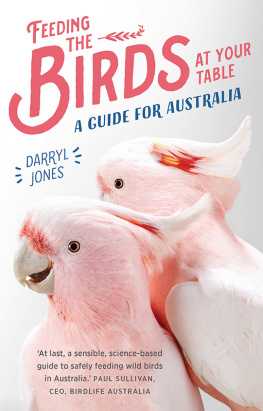

Next, out with the seed. Crested pigeons come quickly, followed by two rainbow lorikeets (there are fewer blossoms around for them in the winter season) and, inevitably, a bunch of galahs with their chubby cheeks and soothing plumage of pink and grey. These are the standard neighbours; they come every time.

More unpredictable are the king parrots, usually in pairs, he with his crimson head and deep green body and wife with red undercarriage and more cautious approach. As the deck is invariably overcrowded, I reach for some china, a posh tea plate, fill it with seed, and place it on the table. The kings gracefully walk to each side of the dish and begin to eat, gurgling slightly as they do so. If a parrot twice their size barges in, I lift the dish and prepare to leave, but sometimes (thrill!) the male leaps on to my wrist and from there continues to feed from the plate Im holding. I freeze, often for long periodsthis is especially trying in the winterwhile these exquisite native parrots have lunch. The Greek family next door look, nod and say, How good is that!

Sometimes we have crows, more flighty than the rest, eventually settling, but flying off at the slightest disturbance. We miss old Pegleg, who was a regular years ago, with his one stump still displaying coils of fishing line which we longed to remove, but could never get close. Red-browed finches used to visit in packs of ten or twelve, but no more.

Pegleg, like other corvids (and I include currawongs and magpies here, though the latter are in a different classification), bring their offspring to our smorgasboard and teach them that it is safe. They do this by flying down off the rail and demonstrating that its okay to browse. We delight in the varied and subtle behaviour weve seen over the years: maggies taking hard bread to water to soften it; the patience of mothers with demanding chicks; the ranking of aggressiveness among species with lorikeets and corellas at the top (corellashave you seen their eyes?just like ET). Some birds are obviously used to humans and try to come into the house. This gets me into trouble: Im too lenient.

Sulphur-crested cockatoos are obviously the most outrageous at home invasion. One or two walk solemnly through the open doors from the deck, leap up onto the back of the sofa, look at me and nod, giving a small squawk. This is the signal for me to fetch a shortbread biscuit. This is grasped by one foot and brought to the beak for consumption, crumbs liberally dropping to the floor. When one biscuit is finishedanother nod and squawk, and I oblige with another.

On one occasion I had no treats handy so the cockie leapt on to the coffee table and solemnly began to devour pages from the large atlas lying there. I also get told off about their habit (though the galahs are worse) of chewing the framework of the deckthe railings especially. Deep gouges now line the woodwork. I take it as a natural souvenir from our visitors. My partner Jonica Newby does NOT agree.

Magpies, of course, were quick to come through the doors. Within a metre of the entrance they would, without fail, need to drop another kind of souvenir, a white splat with black and grey. I would leap to clear it up to keep the avians and me out of trouble. But never quickly enough. Jonica would shoo them out and train them, loudly, to respect the clear boundary between inside and outside. The magpies are immensely smart and learned the lesson almost instantly, but are often willing, as time passes, to test our vigilance.

But it is instructive to talk to Jonica about how she approaches training. The magpie, having been chased out a few times with shouting or a flung soft pillow, comes towards the open French windows and stands on one leg just before the shining floor of our lounge. Then it slowly lowers the other foot just inside the housebarely a centimetre over the line clearly marking the start of inside. As that trespassing toe hits the floor, Jonica shouts very loudly. At that instant the bird learns the lesson, it knows exactly what the limits are. They are smart creatures, Oz birdies.