Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Something in These Hills

Something in These Hills

The Culture of Family Land in Southern Appalachia

John M. Coggeshall

The University of North Carolina Press CHAPEL HILL

This book was published with the assistance of the Fred W. Morrison Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2022 John M. Coggeshall

All rights reserved

Set in Merope Basic by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Coggeshall, John M., author.

Title: Something in these hills : the culture of family land in southern Appalachia / John M. Coggeshall.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022015996 | ISBN 9781469670249 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469670256 (paperback ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469670263 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Appalachians (People)Land tenureSocial aspects. | Land tenureSocial aspectsAppalachian Region, Southern. | Appalachians (People) Ethnic identity. | Appalachian Region, SouthernCivilization. | LCGFT: Ethnographies.

Classification: LCC F210 .C64 2022 | DDC 975.6/9dc23/eng/20220420

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022015996

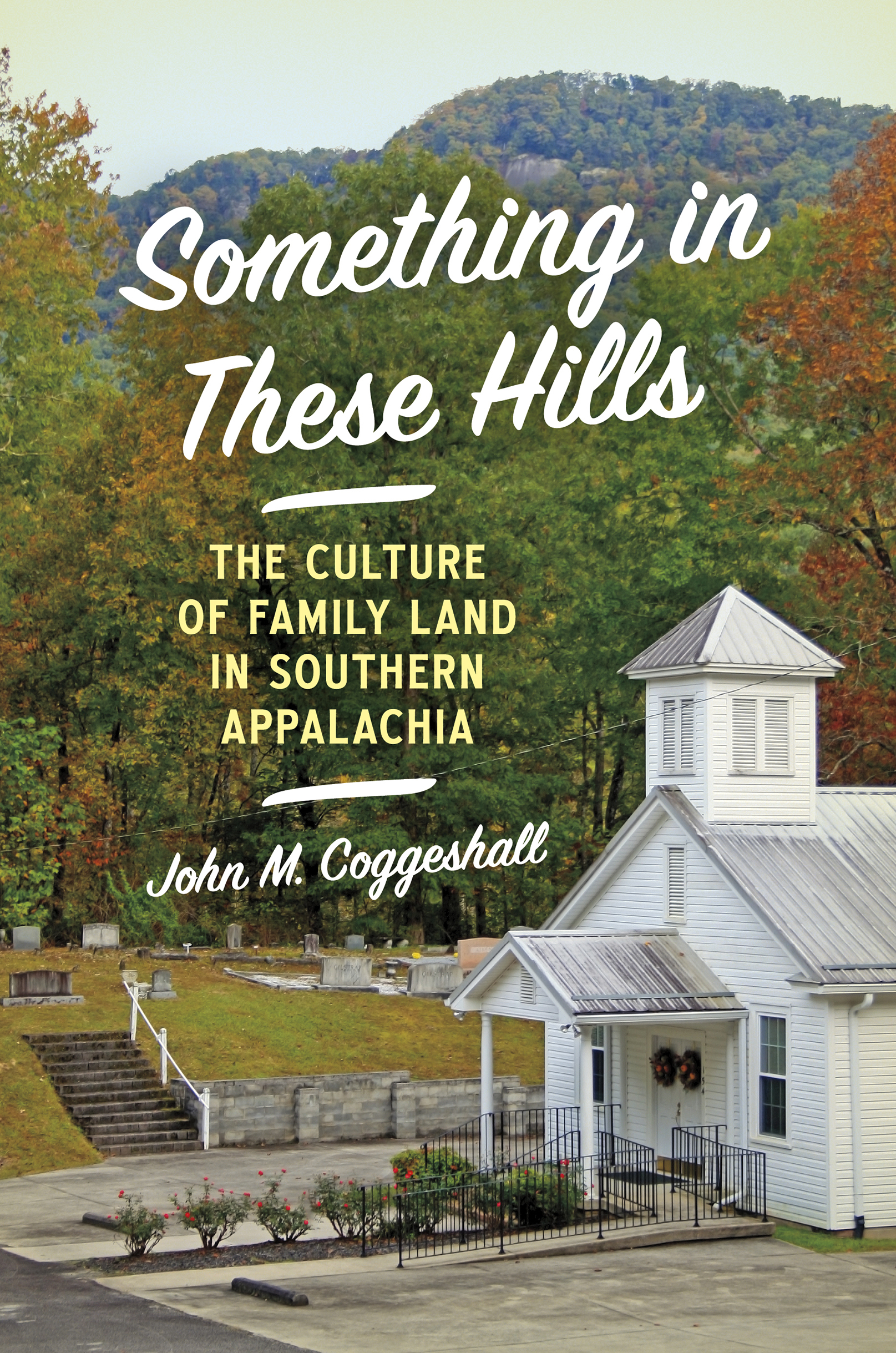

Cover illustration: Rocky Bottom Baptist Church, Pickens County. Photo by the author.

To my parents, John H. and Myra Coggeshall.

Above all else, you gave me two things: roots and wings.

Contents

Acknowledgments

In many ways, this book has reminded me of what I love most about being an anthropologist: the opportunity to help give voice to those whose voices may have been ignored or overlooked and to restore dignity and respect to those lives.

To the best of my recollection, this research project began with a request sometime in the late summer of 2006 by Tom Swayngham and Greg Lucas, both with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (DNR), to document the lives and stories of the old-timers who had lived in the Jocassee and upper Keowee Valleys of Pickens and Oconee Counties, South Carolina. Tom and Greg also provided me with an initial list of contacts and invited a retired DNR biologist, Sam Stokes, to help me meet these folks. Sam and I enjoyed many trips together in my first year of research, and he introduced me to some amazing people. Unfortunately, Sam passed away on June 24, 2019.

Both Tom and Greg have demonstrated incredible patience as their initial hopes for a collection of stories from the old-timers has morphed into two prequels: Liberia, South Carolina (University of North Carolina Press, 2018), about an enclave of descendants of formerly enslaved African Americans in upper Pickens County, and then this book. While it took me several years to realize it, many people in the mountain counties talked about their family land in ways that differed from that of general American culture. That difference then inspired me to present their perspectives in this book before I offer a collection of mountain stories in a future work.

Fieldwork formally began in the early fall of 2006, with the bulk of my interviews taking place in 2008 and 2009 but continuing into 2012. I would like to thank the eighty-eight men and women of Greenville, Pickens, and Oconee Counties who volunteered their time and memories for the interviews that have enhanced this study. While all of you may not be quoted in this book, I sincerely enjoyed having the opportunity to meet you and listen to your perspectives.

Since the beginning of fieldwork, twenty-one individuals have passed away. I would like to remember and thank Sam and Leecie Baker, Bill Batson, Brown Bowie, Lloyd Cannon, Lester Chapman, Dock and Alice Crowe, Blanche Burgess Hannah, Gerald Holcombe, Jefferson J. D. McGowens, Oliver Hub Orr, Albert A. C. Owens, Grover Owens, Robert Perry, Frank Porter, Ann Poulos, Charles Powell, Edgar Smith, Sara Snow, and Pauline Thrift. It was a great pleasure to have had the opportunity to sit and talk with you.

The Harry Hampton Memorial Wildlife Fund, partnered with the South Carolina DNR, provided $9,500, and the Clemson University Research Investment Fund Program added another $6,000 to support the Jocassee Gorges Cultural History Project, under which I interviewed the mountain residents. Almost all of this money paid the Clemson University graduate and undergraduate students who transcribed the interview tapes, and I am grateful for the professionalism and patience shown by all of them. During the course of ten years, forty-six students helped to transcribe the interviews. With apologies to Rudyard Kipling, while Ive likely overworked you, and severely underpaid you, I sincerely, deeply thank you, undergrads.

Friends and colleagues have read various drafts of chapters, the entire manuscript, or both, and I am grateful for the thoughtful and helpful suggestions from Wes Cooler, Karen Hall, Greg Lucas, Cathy Robison, Cindy Roper, Tom Swayngham, Randy Tindall, and Melinda Wagner. I also appreciate the comments from the two anonymous reviewers for this manuscript who helped me to extend its theoretical direction, rethink some details about its organization, and add some concepts.

One of these reviewers described the manuscript as readable, and, with photographs, it would be stunning. I had hoped to pay for a professional photographer by submitting an internal Clemson grant, but unfortunately the pandemic prevented that possibility. Instead, most of the photographs appearing in the book are my own. I obtained a better Oconee Bells photo from a friend, Sue Watts, and received permission from Bob Spalding to use his photo of Bobs Place before the fire. I sincerely appreciate the help of these individuals. But to improve my own photos, a good friend from my graduate school days, Randy Tindall, offered his professional photo-editing advice free of charge. Randy rejected or approved the photos I sent him and offered editing advice on cropping and shading. If the book truly has transformed from readable to stunning, it is thanks to Randy Tindall.

Thanks to Lucas Church, acquisitions editor at the University of North Carolina Press, for encouraging me to submit the original manuscript and to usher it through the revisions process. Thanks also to Erin Granville, managing editor, for guiding me through the final edits and page proofing stages. I also appreciate the technical editing contributions of Michelle Witkowski and Yvonne Ramsey at Westchester Publishing Services. Thanks also to Allison Daniel and Hannah Taylor, both with Professional Editing at Pearce (Pearce Center for Professional Communication, Clemson University), for compiling the index. I also sincerely appreciate the proofreading assistance from Clemson undergrads Darby Alvarenga, Jupiter Chastain, Alyssa Ciccone, Abby Cram, and Rose M. Keller.

Finally, I want to thank my wife, Cathy Robison, for giving me the time, space, and love to see this book through to completion.

Something in These Hills

CHAPTER ONE Opening the Black Box of Landscape

Examining Southern Mountain Concepts of Place

Introduction

Where the Blue Ridge yawns its greatness is the opening line of Clemson Universitys alma mater song, generating images of the majestic southern Appalachian Mountains within an hours drive of the campus located in upper South Carolina. But in contrast, the slow, ominous opening notes from a dueling banjo and guitar produce entirely different images of these same mountains. Both tunes describe the same granitic cliffs, deep valleys, and tumbling rivers of South Carolinas Blue Ridge, in the northwesternmost part of the state. Perhaps there is something in these hills, as Clemson alumnus Joe Sherman penned in the universitys most iconic and resonant phrase. But what is this something that generates feelings of both beauty and danger from the same geophysical features? Translating these deeply felt emotions into words and concepts that outsiders can comprehend is the subject of this book.