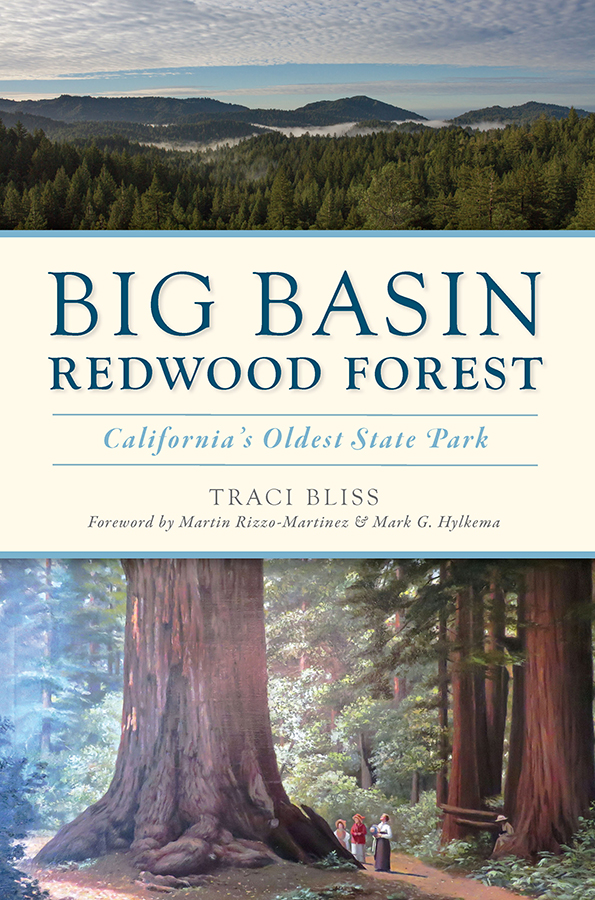

FOREWORD

The Santa Cruz Mountain range, in which Big Basin is a central feature, was home to several California Native American tribes whose people defined their homelands and territories through connectednessancient linkages of both kinship alliances and economic interactions.

This book examines the extraordinary steps taken to protect the so-called wilderness lands now known as Big Basin Redwoods State Park, which many would eventually consider the birthplace of the environmental movement. It is important, though, to remember that the Santa Cruz Mountain range comprised the homelands of Indigenous people such as the Cotoni for thousands of years. For them, this earth was far from wild.

The Cotoni and their ancestors certainly shared the same sense of sacred awe over the majesty of the redwoods that later environmentalists and the rest of us feel, but theirs came from an intimate knowledge and familiarity with the abundant resources available in these lands. The very idea of preserving an untouched or pristine wilderness was built on erasure, consciously or not, of the long history of Indigenous land management practices that took place in their homelands.

Over many thousands of years, the Indigenous people developed techniques for tending the natural world to increase its bounty. Each tribe consisted of groups of families residing in a few neighboring villages, and territories were largely determined by the resource patches a given community could productively manage. Tilling meadows to improve the growth of edible bulbs and the intermittent controlled application of fire were among the effective strategies for creating successions of diverse and healthy plant communities.

Among the many Ohlone language dialects spoken by the Indigenous peoples of the Santa Cruz Mountain range, some called the mountains Mak-Sah-Re-Jah. In historic times, the eighteen thousand acres of Big Basin State Park were the ancestral homelands of an intersection of tribal peoples, principally the Cotoni and the Quiroste, although mostly the former. The Rancho del Oso area of the park along Waddell Creek appears to have been a boundary (or mutual lands) between the Quiroste and Cotoni, with the Cotoni living south of the creek and the Quiroste to the north. The Big Basin park entrance sits in what is now called Saddle Mountain; this area was once the vicinity of what we believe was the large Cotoni village known as Achistaca.

Several archaeological sites are scattered along Ben Lomond Mountain directly above the park and provide evidence that Native people maintained patches of meadows and oak woodland within the parks forest; the finding of chipped stone flakes that were once used to cut stems and shoots testify to their gardening work and stone tool maintenance. The larger community of Cotoni people also had residential villages on the coastal terrace below the mountains, at Davenport and Scott Creek, thereby assuring access to marine resources.

The Cotoni were part of a wide-ranging trade network of shell bead exchange and abalone ornament production fueled by consumer demand throughout interior California, and the tribe was able to control the export of these commodities to maintain their value. In return, exotic materials like obsidian, used for chipped stone spears and arrowheadsfrom quarries in both the eastern Sierra and north Coast Rangewere available to the Cotoni through long-distance trade connections.