Table of Contents

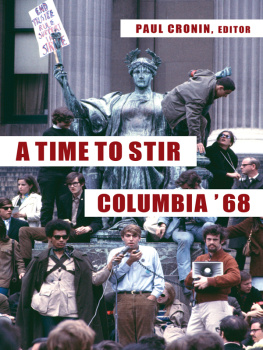

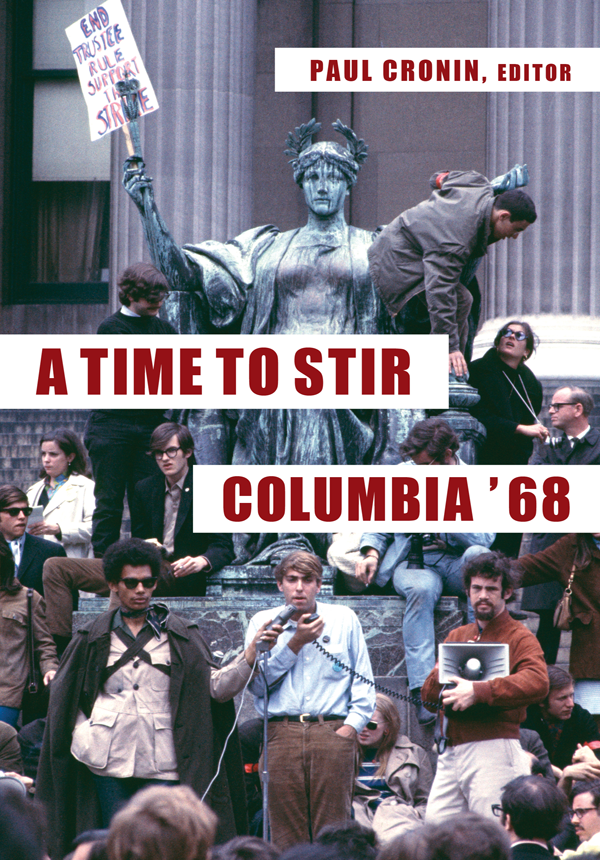

A TIME TO STIR

PAUL CRONIN, EDITOR

A TIME TO STIR

COLUMBIA 68

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54433-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cronin, Paul, editor.

Title: A time to stir: Columbia 68 / edited by Paul Cronin.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017024004 (print) | LCCN 2017040035 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231544337 | ISBN 9780231182744 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Columbia UniversityStudent strike, 1968. | Students for a Democratic Society (U.S.). Columbia University Chapter. | Columbia University. Students Afro-American Society. | Student movementsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | African American student movementsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | Student protestersNew York (State)New YorkBiography.

Classification: LCC LD1250 (ebook) | LCC LD1250 .T56 2017 (print) | DDC 378.747/1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017024004

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover image: Archive Photos/Getty Images

In memoriam

Peter Haidu

and

Harold Wechsler

When the country, into which I had just set my foot, was set on fire about my ears, it was time to stir. It was time for every man to stir.

THOMAS PAINE

Columbias problem is the problem of America in miniature.

TOM HAYDEN

CONTENTS

What we learned during those six days of the building occupation was the transformative power of individuals working together in pursuit of justice.

As one of only sixteen black freshmen included in the approximately eight hundred students in the class of 1969, we were outsiders who, by our very presence, became agents for change at Columbia.

The fourth estate never seemed to understand that the black students occupation of Hamilton Hall was the pivotal act of the Columbia protest, not an ancillary coda to a New Left uprising.

By 1968, an environment existed where there was great legitimacy given by a large percentage of young people to the underground press.

Police on the Columbia campus thought of the protesters as ungrateful, spoiled little rich brats.

There was an active effort inside the buildings to avoid creating and enacting systems that reflected the hierarchical social structures we were battling.

I was representing Fayerweather Hall on the hastily assembled Strike Steering Committee, a body largely dominated by male undergraduates from SDS.

Like other Praxis Axis people on Columbia SDSs steering committee, I felt it wasnt enough for Columbia SDS to be a cute guerrilla-theater, radical-education, draft-counseling, petition-signature-gathering, purely agitational organization.

The revolutionary task confronting intellectuals was to begin the long march through the institution that was our field of activity: the university.

We feared that the rational core of the university was exploding in slow motion around us and might never be put right.

By 1968, my view of Columbia was that of an SDS organizer who would do all he could to speed up the cultural and political change that was taking place across the nation.

Whether working down in Mississippi or as a prosecutor in New York City, I was obligated to defend the Constitution, enforce the law, and uphold the rights of everyone.

Within a day or two, the story of the Columbia occupations became a national story, and the Office of Public Information began to assume the role of de facto headquarters for the national press.

In April 1968, I was a second-year architecture student primed and ready for the events that were about to engulf Avery Hall into the tumultuous Columbia University strike.

We are a handful of Afro-Americans who have demonstrated the smarts to garner admission to this prestigious institution of higher learning.

Philosophy Hall, occupied by the Ad Hoc Faculty Group, was in disarray. People milled about, but with no sense of direction.

That students were experiencing the weight of responsibility inevitably accompanying a commitment to liberation was profoundly noble, but also tragic.

I felt compelled to help somehow, but the demonstrations at Columbia seemed far from the real world, and I questioned the efficacy of protesting within the protective walls of the university.

Columbia 1968 shows what an extreme situation looks and feels likethe tensions and costs, the hopes and possibilities, the dangers of extremism and complacency.

We were making history. However we had gotten here, we were boys and girls, working and living together, crying out with our bodies for humanity and for our beliefs, and for a while we were winning.

The Columbia protests were fundamentally about the politics of domination. Ironically, however, it quickly reproducedright there in its zone of liberationthe very dynamics it was rebelling against.

When is it correct to take action against a government, even one that has been legally installed? How is legitimacy definedmorally or legally?

Columbia was engaged in a massive campaign of evictions that was transforming a viable and healthy mixed community into a sterile institutional enclave.

On every level, supposedly solid and normative conventions and institutions were shifting or crumbling.

Inside Fayerweather we experienced a beautiful, magnetizing communal life, but also fear and paranoia, and learned to live with each other in a cloud of stress.

We Fayerweather folks were not revolutionaries intent on destroying the existing order but reformist progressives committed to the goals of ending the war in Vietnam and combating racism at home.

The universitys leadership, led by President Grayson Kirk, had no clue that times were changing, and their indifference to students concerns only amplified our anger.

Just as the presence of Mayor John Lindsay was unlikely to bring about some meaningful resolution of the situation at Columbia, bringing in the New York City Police Department also was unlikely to be helpful.