Preface

Oskee-wow-wow Illinois,

Our eyes are all on you.

At the start of the sixties decade, I was twelve, the eldest of six children of an Italian Irish working-class Catholic family, an altar boy, a good student, and the neighborhood paperboy. Early one morning as I folded my stack of Illinois State Journal newspapers, one after the other, half-awake, a front-page photo of Protesting Japanese students caught my eye. The picture perplexed me, and eventually I paused and asked out loud, Who are these students? Are they students like me? What are they doing? The subject of the protest was unimportant; the idea of students publicly protesting authorities for any reason completely flummoxed me. The image simply did not fit into my worldview, formed by Dominican nuns at the Little Flower School in Springfield, Illinois. That worldview was largely shared by my fellow midwestern citizens, who believed the role of students was to study hard, listen to and respect teachers, and accept their parents views. But that image of protesting students, so outside the midwestern norms of 1960, would soon become an iconic symbol for the decade.

Five years later I enrolled at the University of Illinois at the Urbana campus, ninety miles from home, and over time became one of those protesting students, much to the embarrassment, disappointment, and sometimes anger of Springfield friends and family. When I returned home on holiday breaks, my long hair would elicit anger from my father, an 82nd Airborne World War II veteran, my high school drinking buddies would look askance at me, and my little Italian grandmother would look crossly and mutter about heepies. Within three blocks of my home lived two families whose sons would die in Vietnam. Sargent Michael Calandrino was my age, a star catcher on our little-league team. Private First Class William Hellyer was the ministers son at the Protestant church down the street. Hellyer, a few years older than I, had passed his paper route on to me.

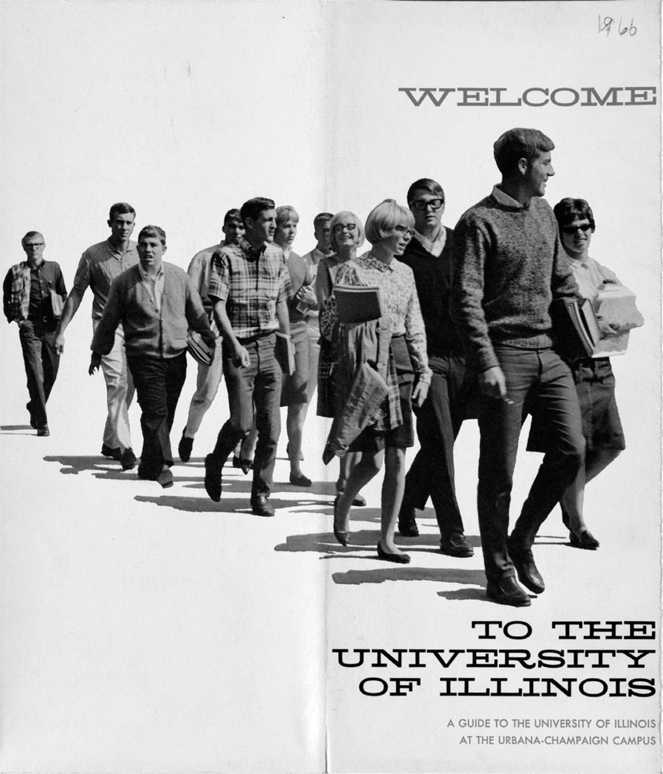

New Student Guide, 1966. Photo courtesy of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Archives, image Welcome to the University of Illinois, 1966, record series 39/1/806.

Many of the norms I grew up with in Springfield, which my generation was taught so well, would be questioned and cast aside in our university experience, as large cultural upheavalsthe civil rights movement, an antiwar rebellion, the drugs, sex, and rock and roll of the sixtiesswept across the nations campuses. The protesting students of the sixties were young, confident, and quite certain; the issues were clear, the conditions called for change, and their movement would be a catalyst for that change.

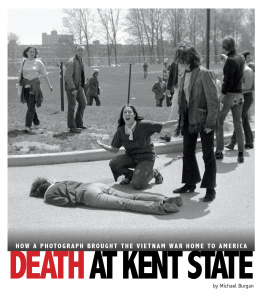

I was a part of the student movement on the Illinois campus for the most turbulent years, 1965 to 1970, participating in rallies, marches, sit-ins, and, I confess with mixed feelings, the riots at the end. Given my role as a participant in the drama, Ive attempted to keep personal opinions confined to the front and back material, employing as much objectivity as possible in the body of the text, using newspaper records, university archives, interviews with participants, and academic dissertations as sources. The award-winning Daily Illini student newspaper, known as the DI on campus, with all back issues now available online, was an especially valuable primary source. During this period, the newspaper staff was blessed with some future journalistic stars such as Roger Ebert, Pulitzer Prize winner and forty-year film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times ; Dan Balz, a Washington Post political correspondent; and Roger Simon, New York Times bestselling author and Politico columnist.

Why study the sixties? As divided as our country is today, it was just as divided, if not more so, a half-century ago. The most notable difference between then and now is that the hope, optimism, and self-confidence of the student movement of the 1960s is nowhere to be found today. In that earlier time, protesting students firmly believed they were about building a better world. Raised in an era of relative affluence and optimism, they had little reason to doubt themselves or the idea of American exceptionalism with which they were raised. They were children of a prosperous age, born amid a booming postWorld War II economy of unprecedented middle-class growth, and as the privileged children of that class, they enjoyed the domestic calm of the Eisenhower years. That same Eisenhower, in his farewell address to the nation, would foretell the troubles of the sixties, warning of the rise of what he called the military-industrial complex, the mutually beneficial relationship that had developed between the corporations and individuals who design and manufacture the nations armaments, and the government officials and armed forces personnel who purchase those same products. A World War II hero, Eisenhower would warn his fellow citizens that they must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought by these powerful interests. Years later, antiwar protesters would lay partial blame for the Vietnam War at the feet of that very groupcorporations, the military, the governmentaccusing them of seeking economic gain from the conflict.

In contrast with the domestically sedate 1950s, the decade of the sixties brought major disruptiona civil-rights movement, assassinations, domestic riots, a foreign war, an unprecedented student-led uprising against that warand the prosperity of the postwar economic times would end soon after, for some Americans never to return. Many of the issues born in the sixties remain unresolved in todays America: a collapse of trust in institutions such as government, media, big business, and the church; culturally disruptive forces that would come to be known as identity politics, feminism, minority rights, environmentalism; and the recidivist backlash against those forces, so evident in todays political zeitgeist. That certitude felt by the sixties students that a better world was within their reach is conspicuous today by its absence; indeed, today the notion seems almost quaint. By studying the period, we can better understand that spirit, where it came from and why it disappeared, as well as why and how it erupted into such a broad political and social movement when it did.