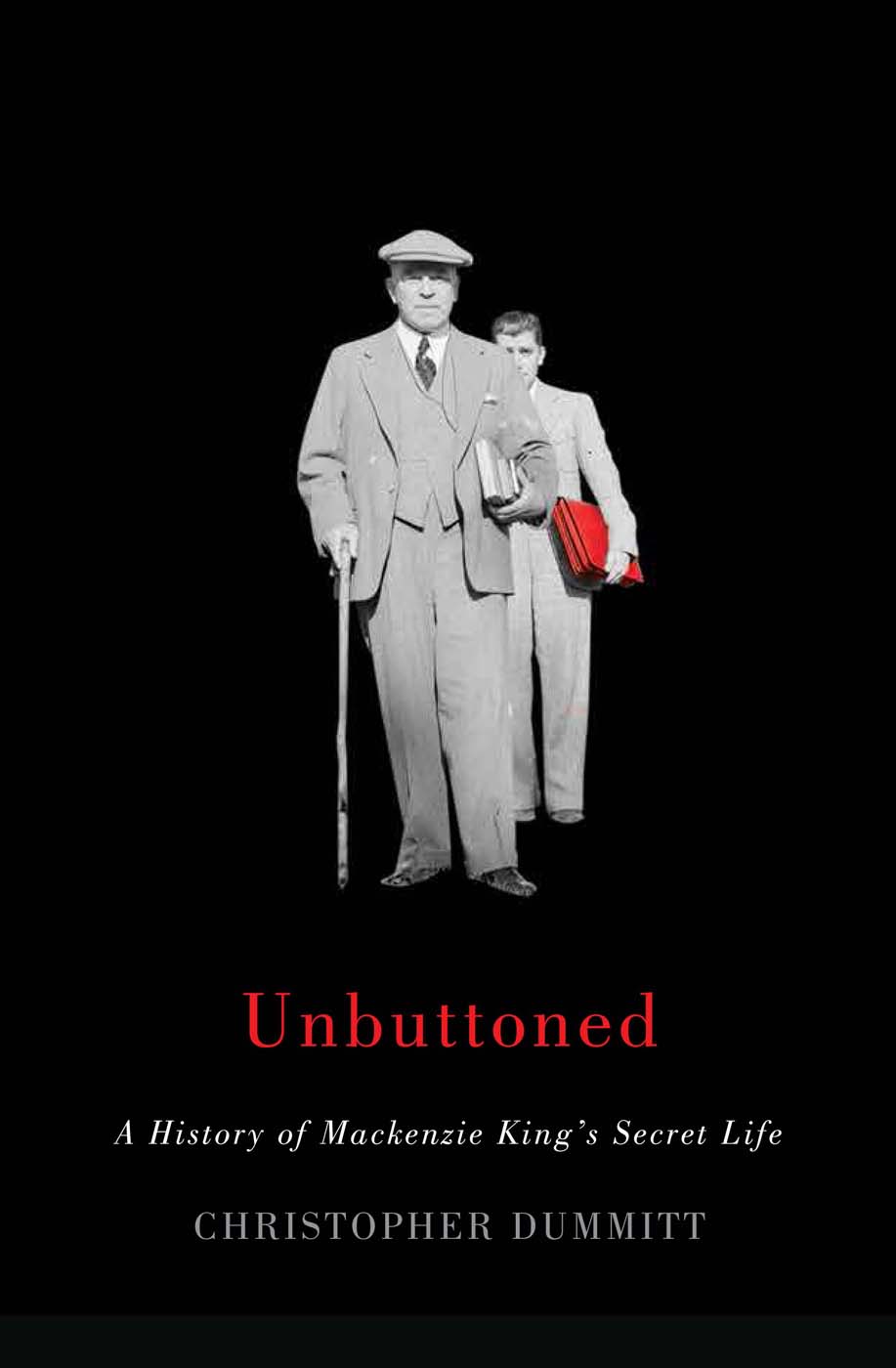

Unbuttoned

Unbuttoned

A History of Mackenzie Kings Secret Life

CHRISTOPHER DUMMITT

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Chicago

McGill-Queens University Press 2017

ISBN 978-0-7735-4876-3 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-7735-4938-8 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-0-7735-4939-5 (ePUB)

Legal deposit second quarter 2017

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

McGill-Queens University Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Dummitt, Christopher, 1973, author

Unbuttoned : a history of Mackenzie Kings secret life / Christopher Dummitt.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-7735-4876-3 (cloth). ISBN 978-0-7735-4938-8 (ePDF).

ISBN 978-0-7735-4939-5 (ePUB)

1. King, William Lyon Mackenzie, 18741950 In mass media.

2. King, William Lyon Mackenzie, 18741950 Public opinion. 3. Prime ministers Canada Biography. 4. Politicians Canada Public opinion. 5. Political culture Canada. I. Title.

FC581.K5S68 2017 | 971.063'2092 | C2016-908162-1 |

C2016-908163-X |

To Juliet and our tribe, Rowan, Finlay, Gilbert, and Arthur

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

Im going to tell two stories in this book. One is the story of how Canadians came to learn about the eccentric private activities that former prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King had managed to keep secret while he was alive. The second story is about the transformation in Canadian culture from the 1950s to the 1980s that gradually allowed many Canadians to talk publicly and irreverently about the details of this former prime ministers secret life.

This book is a kind of narrative history where the argument is largely, though not entirely, developed through the unravelling of a series of events. It moves forward chronologically, retelling the stories of those figures who played an influential role in exposing Kings secrets. Its a book, as the great Canadian historian Donald Creighton might have said, of characters and their circumstances. Readers looking for the usual sorts of things that one associates with peer-reviewed scholarly monographs the review of the academic literature, the positioning of my arguments within theoretical debates, and an acknowledgment, in the text, of the many debts owed to the work of other scholars will not find them here. This is not to say that the book doesnt rely extensively on the work of others (it does), nor that it isnt making an argument that interacts with this literature (it is). But in this book those debts and debates are largely confined to the endnotes.

In some academic circles, narrative history has come to seem old-fashioned. It is supposed to be insufficiently analytical. A postmodern critic might say that it creates an artifice in the form of a story, using realism to hide what it (and its author) doesnt know: history didnt really happen in just that way and to pretend otherwise is just an example of the historian trying to fool the reader and perhaps even

It seems to me that the role of history is to make an earlier era come alive again in the minds of our contemporaries. It wont really be the past, to be sure, but this isnt essential. A map is never the place it represents. Yet the usefulness of history comes from the affinities and sympathy it inspires or the shock of difference it can evoke, even for a relatively recent historical era that used to be, but is no longer, our own. Perhaps a personal analogy can make clearer this point. As a father of four children Ive relived the early years of parenthood again and again and again, each time realizing how little I remembered from the previous child, each time reliving in new ways what I had done before many times but had forgotten. And, of course, it is and is never just the same. This isnt quite what we do in history but its similar. In reliving the memories of what the last child was like, in looking back to ask Is this what a baby does now? Im forced to question what I think I know, to relive what I remember, and to experience it all again. By the fourth baby Ive learned something, though its nothing close to total recall. Nor would I say, because Im a historian, Ive avoided the fate predicted by that usual quotation we employ to justify our existence Those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it. Though (usually) I would hesitate to call parenting my doom, I have indeed repeated the past. Perhaps because I remember what came before I am, sort of, prepared. This, it seems to me, is the most we can ask of history.

The real questions are these: How best to make this past come alive so that others today can relive and remember it in somewhat accurate and useful ways? How to make it poignant? How to make it (sort of) real, or at least allow us to catch glimpses of an earlier time in what can only be, at best, a kind of peripheral vision? My modest ambition is twofold: to eke out a place for narrative history as one legitimate answer to these questions; and to suggest that narrative history isnt just for popularizers or journalists or dead historians. It is possible, I hope, to write a story and to still make a contribution to scholarly knowledge.

Having said all this and forewarned the reader about what will be coming in the book proper, I do want to make space here, over the next several pages, to explain more explicitly how this book does in fact engage with certain areas of contemporary scholarly literature. Were still in the Preface, so the story hasnt quite yet begun.

In his book on the posthumous memorialization of French explorer Jacques Cartier, historian Alan Gordon reminds us of how much interpretations of the past reflect the common sense of their own times. A whole historical subdiscipline now devotes itself to the politics of historical memory and the way in which particular historical figures and events come to be written into history by whom, when, and for what purpose. This book benefits from these works, and certainly from the basic insight that historical memory is always rooted in a particular kind of political project and cultural situation. Yet the goal here is somewhat different. We are looking at only one relatively short period of time, from Kings death in 1950 until the early 1980s. Because King was prime minister for so long, it is likely that he will continue to show up again and again in Canadian historical writing and in the broader culture, taking his place as someone whose life and career can speak to other kinds of concerns.

But this book addresses an accident the fact that King died when he did and that he had secrets to reveal, and that these secrets were written in a diary that was ultimately opened up to the public at a propitious moment. It was a chance event, an example of a concept that historians prize almost above everything else: contingency. This book isnt concerned so much with the many changes in historical meaning of Mackenzie King as it is with the very specific meanings that a couple of generations of Canadians gave to Kings secret life over the course of a few decades in the second half of the twentieth century.

Next page