Text 2011 by David E. Wilkins

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval systemexcept by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a reviewwithout permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

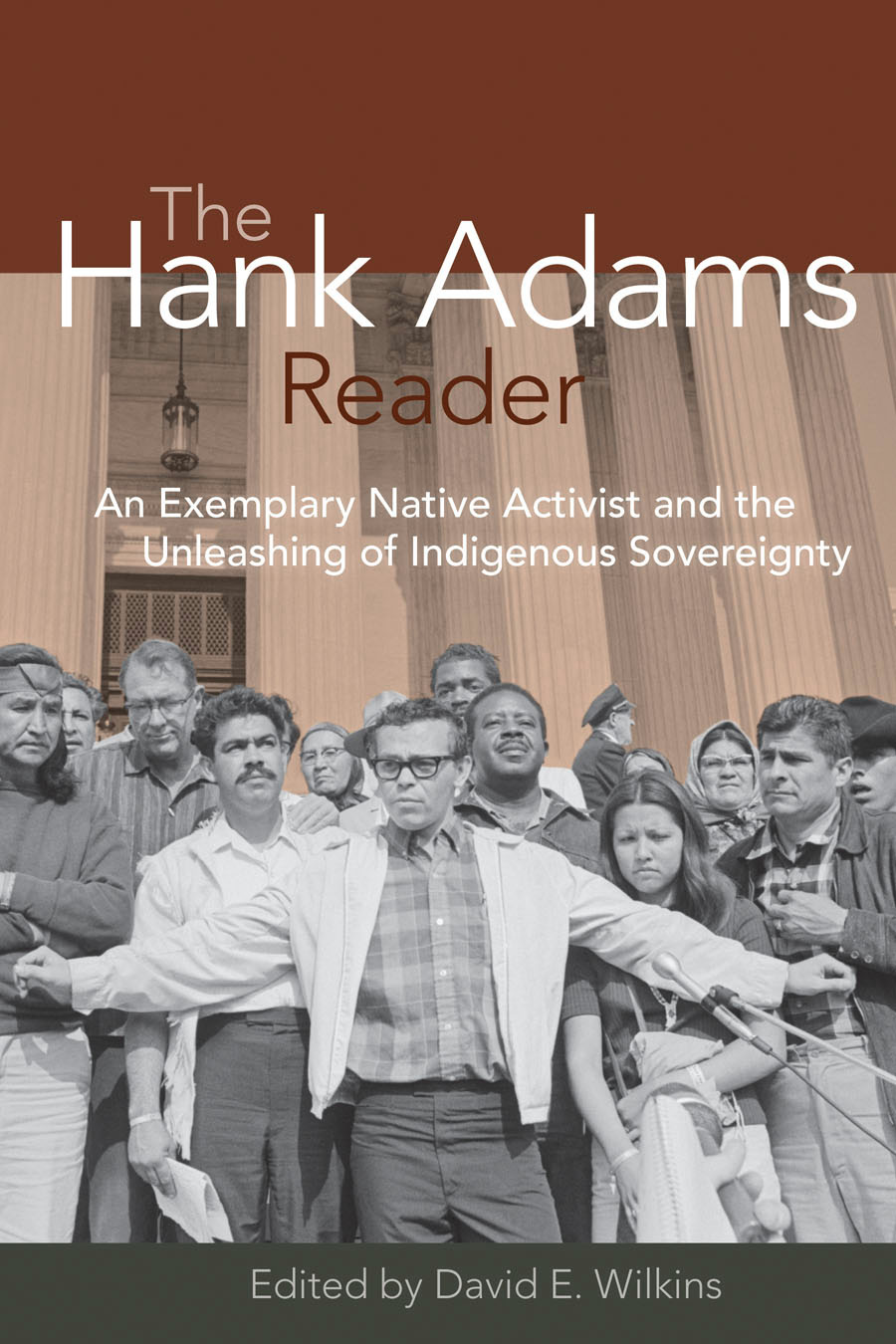

The Hank Adams reader : an exemplary native activist and the unleashing

of indigenous sovereignty / edited by David E. Wilkins.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-55591-447-9 (pbk.)

1. Adams, Henry, 1944- 2. Indian activists--United States--Biography.

3. Indians of North America--Civil rights. 4. Indians of North

America--Claims. 5. Indians of North America--Politics and government.

6. Trail of Broken Treaties, 1972. 7. Wounded Knee

(S.D.)--History--Indian occupation, 1973. 8. American Indian

Movement--History. 9. Self-determination, National--United States. 10.

United States--Race relations. 11. United States--Politics and

government. I. Wilkins, David E. (David Eugene), 1954

E90.A26H36 2011

970.00497--dc22

[B]

2011006043

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Design by Jack Lenzo

Fulcrum Publishing

4690 Table Mountain Drive, Suite 100

Golden, Colorado 80403

800-992-2908 303-277-1623

www.fulcrumbooks.com

Contents

Acknowledgments

I am, as always, grateful to my family for their unstinting love and support: Evelyn, Sion, Niltooli, and Nazhone. And thanks to Sam Scinta for his staunch belief in this project. The librarians and archivists at several outstanding libraries and historical societies provided the bulk of the papers presented in this collection: the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library at Princeton University; the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico; the Minnesota Historical Society; and the Special Collections Library at the University of Washington. And to Daniel Cobb, who was kind enough to share some of his own research with me that featured the early years of the National Indian Youth Council.

My deep appreciation also extends to my two gifted mentors, George Whitewolf (Monacan) and Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux). George devoted his life to resuscitating and sustaining the lifeways of both eastern and western Native peoples, while Vine did the same and was the first person to bring Hanks name to my attention in 1980. Vine and Hank shared a common love for the peoples, the lands, and the cultures of the Northwest Coast and admired them for, among other things, their dedication to the perpetuation and enhancement of treaty rights.

A hearty thanks also to Nicole Gruhot of the University of Minnesota, who skillfully typed the entire manuscript, and in her spare time no less. I am also deeply appreciative of Carolyn Sobczak, whose excellent editorial skills helped clarify and strengthen the book.

Of course, this work exists only because Hank Adams has spent his entire adult life exercising his personal sovereignty to help enhance the collective sovereignty of Native peoples in the northwest corner of the United States. But Hanks brilliant writings, testimonies, and diplomatic skills have influenced indigenous peoples and their intergovernmental relations throughout North America and parts of Central America as well.

Foreword

Billy Frank

Hank Adams has been my good friend for more than fifty years.

I first met the skinny Indian kid with black-rimmed glasses at small intertribal meetings in the early 1960s. We were trying to figure out what we were going to do about the state prohibiting us from selling our steelhead, which they classified as a game fish. He was with the Quinaults and wasnt much more than a teenager at the time, but you could tell he was smart.

Months later, I was out on Nisqually Cutoff Road one day when he stopped to ask me for directions to Franks Landing, my familys home for many years. He was there to organize the fight for treaty fishing rights. It was the beginning of a long journey for us and our families. In the years that followed, he became a brother to me.

Weve been through a lot together: getting beaten up, arrested, and jailed. Those were hard times, but we laughed a lot. I started calling Hank Fearless Fosfrom the character in the Lil Abner cartoon stripafter he got shot while tending a net on the river. I still call him Fearless today, because thats what Hank is. Hes fearless.

It was Hank who kept us going throughout the long struggle for treaty fishing rights that led to the Boldt decision, in 1974. He has always been there for us. Even after he was drafted into the army, he found ways to keep on helping us, coordinating our efforts, building support from elected officials, and finding a little money to keep us all going. Im not sure that we could have done it without Hank. He was everywhere, all at once, organizing, strategizing, and communicating.

Hank is one of the great thinkers in Indian Country. He remains a trusted adviser to many. I talk to him every day, because the fight continues every day and will never be over.

Hanks whole life has been dedicated to helping Indian people, but he has really helped all citizens of the United States. He is not just a champion of treaty rights. He is a champion of civil rights for all people.

He could have been many things: a lawyer, a professor, a politician. But those jobs would have just tied him down.

Hank shoots for the stars, and thats what hes been doing for his whole lifetime. Were just tagging along.

Introduction

Social movements, like the struggle for womens rights, the unemployment workmens movement, the environmental movement, the Black Power movement, and others, ripen when a series of unpredictable forces coalesce, signaling that there is an opportunity for change. This need for change or, better yet, transformation is sometimes precipitated by a significant eventthe death of a key person, the enactment of a particular law or court decision, or a natural catastrophethat then combines with a mixture of forces that may be fed by anxiety, stress, ideology, excitement, or raw power imbalances.

Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, in their classic study Poor Peoples Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail , emphasize that the emergence of a protest movement entails a transformation both of consciousness and of behavior. The transformation of consciousness, they argue, has three aspects. First, the established system is viewed as having lost legitimacy. Second, the members of the protest group, who had previously accepted the status quo, now begin to demand rights. And finally, the people come to believe that they have the power to change conditions for the better.

The transformation in behavior is also remarkable and typically involves two features. First, masses of people become defiant: they violate the traditions and law to which they ordinarily acquiesce, and they flout the authorities to whom they ordinarily defer. And second, their defiance is acted out collectively, as members of a group, and not as isolated individuals.

While social movements may have multiple causes, their goals often include multiple desired changesincremental, reformative, and sometimes radicalthat are designed to improve the lives, respect the rights, or protect and enhance the resources of a groups members.

![Deloria Jr. - Behind the trail of broken treaties an Indian declaration of independence. [The goundbreaking work by the preeminent spokesperson for American Indian rights]](/uploads/posts/book/171989/thumbs/deloria-jr-behind-the-trail-of-broken-treaties.jpg)