Copyright 2006 by John OSullivan

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans-mitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, website, or broad-cast.

Regnery is a registered trademark of Salem Communications Holding Corporation

This e-book edition published 2016, ISBN: 978-1-59698-034-1

Originally published in hardcover 2006 and paperback 2008

Cataloging-in-Publication data on file with the Library of Congress

Published in the United States by

Regnery Publishing

A Division of Salem Media Group

300 New Jersey Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20001

Distributed to the trade by

Perseus Distribution

250 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10107

Manufactured in the United States of America

Books are available in quantity for promotional or premium use. For information on discounts and terms, please visit our website: www.Regnery.com

To my mother

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

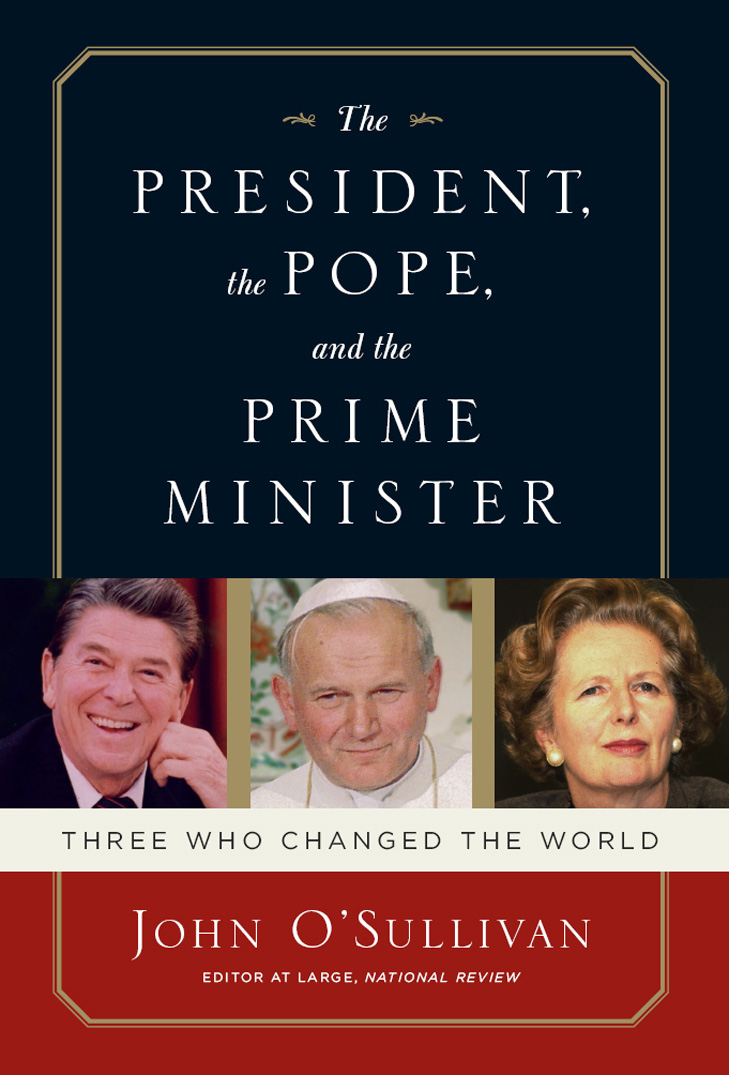

A s the 1970s began, three talented middle managers worried about their respective institutions, which seemed to be crumbling. Worse, there seemed little they could do about it. All three were, in the jargon of management, on the edge of the boardroom, not at the center of events and decision-making.

Karol Wojtyla was the cardinal-archbishop of Cracow, Polands second city, in a Church still dominated by an Italian pope and Italian clerical bureaucrats. Margaret Thatcher had just entered the cabinet of Edward Heaths new Conservative government in the middle-ranking position of minister of education. Ronald Reagan was in his second and final term as governor of California.

All three had strong personalities, great abilities, and loyal followings. Two of them had good prospects.

Wojtyla might conceivably rise to become the Catholic primate of Communist Poland and an influential religious leader in an Eastern Europe then adjusting to the permanence of Soviet rule. Thatcher might become Britains first female chancellor of the exchequer (finance minister in non-medieval language) if her wildest ambitions were realized. She conceded at the time that the post of prime minister would remain beyond the grasp of a woman for many more decades. Both were still rising stars.

At the age of sixty, however, Reagan was probably basking in the warmth of his last hurrah. The Rights favorite had failed in a late bid for the Republican Partys 1968 presidential nomination, and now his successful, more moderate rival, Richard Nixon, was almost certain to run for re-election in 1972. The Californians presidential prospects looked highly uncertainhis national future perhaps limited to a return to the mashed potato circuit of political lecturing. On the verge of receiving his first Social Security check when the 1976 primaries opened, Reagan was already dangerously close to becoming an elder statesman.

All three were plainly at or near the peak of their careers. And those peaks were tantalizingly short of the very top.

It was not hard for any intelligent observer to explain why these three, with such high abilities, had obtained only limited success. All three were handicapped by being too sharp, clear, and definite in an age of increasingly fluid identities and sophisticated doubts. Put simply, Wojtyla was too Catholic, Thatcher too conservative, and Reagan too American.

These qualities might not have been disadvantages in times of greater confidence in Western civilizationor in moments of grave crisis such as 1940 in Britain, or 1941 in America, or in sixteenth-century Romewhen people prefer their leaders to be lions rather than foxes. But 1970 was two years after the revolutionary annus mirabilis of 1968. It was a time when historical currents seemed to be smoothly bearing mankind, including the Catholic Church, Britain, and America, in an undeniably liberal and even progressive direction.

Revolutions of every kindsexual, religious, political, economic, socialwere breaking out from the campus to the Vatican to the rice paddies of the Third World. The sexual revolution of the 1960s, now actually being implemented, was liberating gays, lesbians, housewives, unhappy spouses, single parentsand, of course, those who wanted to sleep with themfrom closets of either silence or irksome duty. Feminism and the United States Supreme Court had added legal abortion to the growing list of womens rights. The Catholic Church had embarked in the previous decade on the internal revolution of the Second Vatican Council; Catholic liberals were now threading through the dioceses of Western Europe and America, purging the liturgy of traditional hymns and high-sounding language and seeking to reconcile faith with secular forms of liberation. The welfare revolution, already entrenched in Europe, was now being extended to America by, of all people, Richard Nixon, with his plans for a guaranteed minimum income and affirmative action. As Nixon also conceded (Were all Keynesians now), the Keynesian revolution in economics was believed to be the key to steadily rising prosperity guided by government and interrupted hardly at all by recessions. The scientific Green Revolution, together with government-to-government aid, promised to extend this prosperity to the poor nations of the Third World. The Third World itself, growing in confidence and clout at United Nations forums, gained more recruits when the Portuguese empire in Africa collapsed overnight, replaced by two new independent governments in Angola and Mozambique. That left South Africa and Rhodesia as the last doomed holdouts against the world revolutions of decolonization and racial equality carried out under UN auspices. There and in countries such as Iran and Brazil, where change was resisted by oppressive governments or the military, more violent forms of revolution were employed. These had been encouraged when armed Marxist peasants in black pajamas had won half a victory in Vietnam as the war wound down, or was at least Vietnamized and American POWs began returning home. But it was generally agreed among progressive opinion that the Vietnam War had been an immoral mistake never to be repeated. More realistic statesmen in the advanced world saw the wisdom of avoiding violence and upheaval by yielding gracefully to other revolutions. Maos China came in from the cold and took its permanent seat on the UN Security Council courtesy of the Nixon-Kissinger opening to China. Edward Heaths Conservative government in Britain not only offered left-wing labor unions an unprecedented say in determining economic policy, but also surrendered Britains recently imperial sovereignty to an embryonic united European superpower. Looking further ahead, the West German government was forging links with the East European Communist regimes in a policy of Ostpolitik that assumed the two halves of Europe would soon converge in some new blend of planned economy and social democracy. Dtente promised the same convergence for the two superpowers, making the threat of nuclear war seem pointless in a world moving inexorably toward a future of peace, love, and bureaucracy.