PART I The Pageant of Experiments with Civilization 1. Experiments in Egypt and Eurasia 2. Rome's Outstanding Experiment 3. The Origins of Western Civilization 4. The Life Cycle of Western Civilization 5. Features Common to Civilizations

PART II A Social Analysis of Civilization 6. The Politics of Civilization 7. The Economics of Civilization 8. The Sociology of Civilization 9. Ideologies of Civilization

PART III Civilization Is Becoming Obsolete 10. World-wide Revolution Disrupts Civilization 11. Western Civilization Attempts Suicide 12. Talking Peace and Waging War

PART IV Steps Beyond Civilization 13. Ten Building Blocks for a New World 14. Moving Toward World Federation 15. Integrating a World Economy 16. Conserving our Natural Environment 17. Re-vamping the Social Life of the Planet 18. Man Could Change Human Nature 19. Man Could Break Out of the Age-Long Prison-House of Civilization and Enter a New World

PREFACE

Table of Contents

LEARNING FROM HISTORY

Human history may be viewed from various angles. The easiest history to write concerns the doings of a few well known people and their involvement in some memorable events. History may also concern itself with inventions and discoveries: the use of fire, of the wheel or smelting metals. It may center around sources of food, means of shelter, or the making of records. It may be concerned with the construction and decoration of cities, kingdoms and empires.

Social history enters the picture with travel, transportation, communication, trade. Human beings group themselves in families, clans and tribes, in voluntary associations; they compete, plunder, conquer, enslave, exploit; they co-operate for construction and destruction. Political history is but one aspect of man's group contacts and group projects.

There have been histories of particular civilizations and of civilization as a field of historical research. With minor exceptions none of the authors that I have consulted has attempted an analytical treatment of civilization as a sociological phenemenon.

Scientists start from hunches, examine available data, advance tentative conclusions, test them in the light of wider observations, and round out their research by formulating general principles or "laws." This scientific approach has been used in many fields of observation and study. I am applying the formula to one aspect of social history: the appearance, development, maturity, decline and disappearance of the vast co-ordinations of collective, experimental human effort called civilizations.

"Assyria, Greece, Rome, Carthage, where are they?" asked Byron. He might have added: "What were they? How did they come into being? What was the nature of their experience? Why did they rise from small beginnings, develop into wide-spread colossal complexes of wealth and power, and then, after longer or shorter periods of existence, break up and disappear from the stage of social history?"

Such questions are far removed from the lives of people who are busy with everyday affairs. In one sense they are remote; in the larger picture, however, they are of vital concern to anyone and everyone now living in civilized communities. If Assyrians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans and Carthaginians built extensive empires and massive civilizations that flourished for a time, then broke up and disappeared, are we to follow blindly and unthinkingly in their footsteps? Or do we study their experiences, benefit from their successes and learn from their mistakes? Can we not take lessons out of their voluminous notebooks, avoid their blunders and direct our own feet along paths that fulfil our lives at the same time that they meet the widespread demand for survival and well-being?

Civilization has been extensively experimental. Several thousand years, during which civilizations have appeared, disappeared and reappeared, have been too brief to establish and stabilize a hard and fast social pattern. As the complexity of civilizations has increased, variations and deviations have grown in number and intensity. With the advent of western civilization a culture pattern is being put together which differs widely from its predecessors.

All civilized peoples seem to have developed from simple beginnings and experimented with broader and more complicated life styles. In western civilization the number of experiments has increased and the span of their deviations seems to have broadened. Under the circumstances an analysis of civilization must take for granted not only social change but the development of, human society along lines which link up the outstanding structural and functional ideas, institutions and practices of successive civilizations.

I propose in this inquiry to state certain accepted facts from the history of civilizations and of contemporary experience. I also propose to analyze the facts and generalize them in such a way that the results of the study may provide an understanding of the human social past, together with some guide-lines that will prove useful in the formulation and implementation of the present-day policy and procedure of civilized peoples, nations, empires and of the western civilization.

This book is not a popular treatise, nor is it a textbook. Rather. it is an attempt to summarize an area of critical human concern. Academia may not use such material: nevertheless it should be available to students and administrators who must plan and direct the social future of humankind.

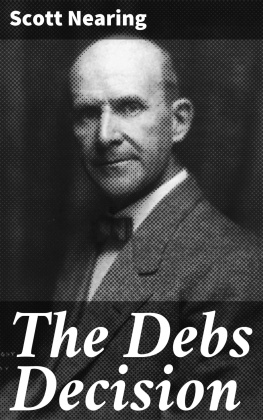

Civilization and Beyond rounds out a series of studies that I began in 1928 with Where Is Civilization Going? The series has extended through The Twilight of Empire (1930), War (1931) and The Tragedy of Empire (1946). Up to 1914 my field of study was confined largely to the economics of distribution. The war of 191418 pushed me rudely and decisively into the broader field. I have described the process in my political autobiography: Making of a Radical (1971).

I hope that this study will provide a useful link in the chain of material dealing with the structure and function of man's social environment, leading directly into an action program that will conclude the preservation and loving economical use of nature's rich gifts and the dedication of thousands of young aspiring men and women to the good life here, now and indefinitely, into a bright, productive and creative future.

As of this date seven publishers have examined the manuscript of this work and declined to publish it. All felt that it would not find any considerable reading public. Nevertheless, I feel that the work should be printed and distributed because it carries a message that may be of first rate importance to the future of my fellow humans.

Scott Nearing.

Harborside, Maine May 5, 1975