Contents

Guide

FOR INA,

WHO LIGHTS UP MY LIFE EVERY SINGLE DAY

Contents

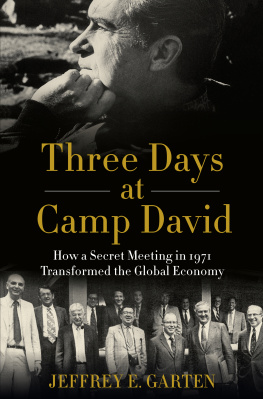

A t 2:29 p.m. on Friday, August 13, 1971, President Richard Nixon walked from the West Wing of the White House to the South Lawn, where he boarded Marine One, the presidential helicopter. A young marine officer crisply saluted the president as he ascended the six steps to the cabin door. The rotary blades atop the fuselage slowly churned horizontally while those on the tail wing began to spin vertically. After a seemingly long moment, Marine One then slowly lifted straight up. Within seconds, its nose dropped, and the aircraft banked to the northwest, flying past the Washington Monument and a landscape of urban buildings. It then flew over small towns and continued over the thickly forested eastern Blue Ridge Mountains on its thirty-minute journey.

Aboard the helicopter, Nixon was crammed in with several menTreasury Secretary John Connally, Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns, Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Paul McCracken, Director of the Office of Management and Budget George Shultz, and White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman. Also on board were two pilots and a flight engineer, two Secret Service agents, and one military aide who carried a suitcase with the nuclear codes.

The seats were upholstered in gold cloth and rested on a rich blue carpet. Nixon had seated himself in an armchair on the right side of the aircraft. With his back to the cockpit, he could look out on the rest of the cabin. A telephone with a long, coiled extension cord was affixed low on the wall, at knee levelthe only source of communication between the passenger cabin and the world outside. The space was cramped; briefcases would have to rest on passengers laps, and a person could barely move down the aisle unless he walked sideways.

Another helicopter had taken off from Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland one hour earlier. On board were Paul Volcker, undersecretary of the treasury for monetary affairs; Peter Peterson, assistant to the president for international economic affairs; Herbert Stein, a key member of the Council of Economic Advisers; William Safire, a White House speechwriter; and John Ehrlichman, director of the White House Domestic Council. Several staffers had departed even earlier by car for the ninety-minute trip.

All these men were headed to a top secret meeting at Camp David, the presidential retreat in Marylands Catoctin Mountain Park. When Haldeman and his deputy, Lawrence Higby, contacted the twelve invitees the prior afternoon, each was told to pack an overnight bag, get ready to leave town for a few days, and under no circumstances tell their families where they were going. In the end, there would be fifteen attendees, including Nixon, Haldeman, and Michael Bradfield, a Treasury lawyer who joined the group on Saturday morning. Only a few participants knew the specific agenda, but most understood that the meeting would be momentous. The day before, George Shultz, the powerful director of the Office of Management and Budget, described his view of the upcoming event to Nixon, saying, This is the biggest step in economic policy since the end of World War II. On the way to their helicopter that very morning, Herbert Stein told William Safire, This could be the most important weekend in the history of economics since Saturday, March 4, 1933 (the day President Franklin D. Roosevelt closed all the banks in America). In fact, the group was about to ignite a series of explosions that would rock Americas political alliances, set the U.S. dollar on a radically new course, and reshape the U.S. and global economies.

THIS BOOK TELLS the full story of that weekendwhat led up to it, what transpired over those three days, what happened afterward, and what it all meant. It is, above all, an account of how the United States began to rethink its role in the world, how it realized it could no longer shoulder all the burdens that were thrust on it after World War II, and how it attempted to redistribute part of its awesome responsibilities to its allies. The events I have written about also illustrate a major inflection point in American history: a moment when the United States, its enormous power notwithstanding, was forced to recognize its growing interdependence with other countries and the need to move from using its raw unilateral leverage to engaging in more multilateral diplomacy and cooperation.

I have told this story through the lens of the U.S. dollar and its relationship to gold. The issues surrounding the American currency may sound esoteric, but in fact the dollar was, and still is, at the intersection of foreign policy, national security, and international commerce. Our currency is also a major influence on what we care so passionately about at home, including such issues as jobs, prices, retirement security, financial stability, economic opportunity, and even respect in the world. We may not think about the dollar in such all-encompassing terms, but the value of the greenback has had a broad and deep impact on the country and the world as well as on our everyday lives.

A BRIEF HISTORY helps to understand the immense challenge facing Nixon and his team as they were traveling to Camp David. At the time of the meeting, the United States had a long-standing treaty commitment, made in the context of joining the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1944, that any foreign government or central bank holding U.S. dollars could exchange them for gold. The actual rate of the exchange$35 per ouncehad been set by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1934, and it had never been changed. In addition, other currencies, such as the British pound, the West German mark, or the Japanese yen, were linked to the dollar at a fixed exchange rate. For example, in 1949 one dollar was worth 360 yen, and the ratio could not vary more than 1 percent either way. That dollaryen rate could be changed more than 1 percent only as a last resort in a long-term emergency. All these provisions were contained in the IMF Articles of Agreement.

These obligations stemmed from a global monetary conference in 1944 at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. It was there that the wartime allies, principally the United States and Great Britain, created a new international monetary framework for the postWorld War II era. The underlying idea was that a global financial systemwith exchange rates that couldnt fluctuate against one another beyond 1 percent, and with rates that were tied ultimately to goldwould provide the stablest possible background for countries to sell one another their grains, food, machinery, autos, textiles, and other products.

The new monetary setup was designed to create a foundation for a world that was much different from the one that existed in the turbulent 1930s. In those earlier years, although countries pegged their currencies to gold, the gold standard was both much more rigid than the Bretton Woods arrangements, and much less internationally supervised. As a result, countries participated inconsistently, and eventually abandoned the system altogether. And once the system collapsedbecause of vicious, unfair competition combined with the economic slowdown of the Depressiongovernments erected barriers to trade, such as tariffs and quotas, that distorted the natural flows of trade and money. They also pushed down their exchange rates to reduce the prices of their exportswhat economists call competitive depreciations.

Here is a simple, hypothetical example of how that worked, and of the pernicious effect on world trade and economic growth that followed: Suppose the German mark had been linked to the French franc at a ratio of one mark to two francs. Assume also that the price of a ton of German steel had cost 10,000 German marks, while the French charged 20,000 francs for the same tonnage. If Germany had devalued its exchange rate by 10 percent against gold and other currencies, it would have essentially discounted their price by 10 percent relative to the French price. Not standing for that, Paris would have proceeded to devalue its currency to underprice the German metal, perhaps pushing down the franc so that a ton of steel cost 16,000 francsa 20 percent depreciation amounting to twice the discount offered by Germany. And so it would have gone, with Belgium and Italy also devaluing their currencies even more than the French did, in order to gain competitive advantage. As Germanys and Frances cheaper exports penetrated the U.S. market, America would have resisted the flood of incoming products by raising its tariffs or by establishing quotas. As imports into the United States contracted, exports to the United States by Germany, France, and other U.S. trading partners would likewise have decreased. Other importers of steel would have reacted the same way the United States did.