DICTIONARY OF CHINESE HISTORY

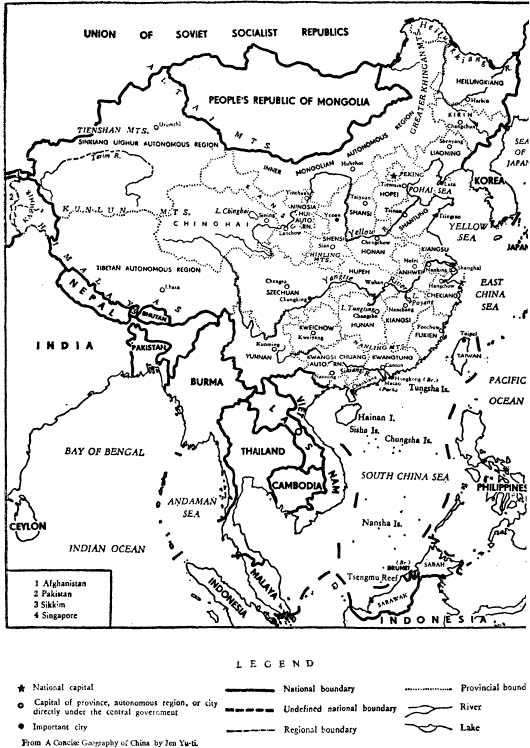

A SIMPLE MAP OF CHINA

Dictionary of Chinese History

Michael Dillon

First published 1979 by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1979 Michael Dillon

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Dillon, Michael

Dictionary of Chinese history.

1. China History Dictionaries

I. Title

951.003 DS733

ISBN 13: 978-0-714-63107-3 (hbk)

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher in writing.

Contents

This Dictionary has been compiled as a handbook for those who are interested in some aspect of Chinese civilisation and would like a guide to the multiplicity of historical events and personalities that are constantly referred to. It is not encyclopaedic, as that would be impossible in a work of this size and probably beyond the competence of any single author. Rather it is an attempt to provide a quick and easy reference to the names and terms which occur most frequently in English-language works on China and which can be usefully explained in a few hundred words.

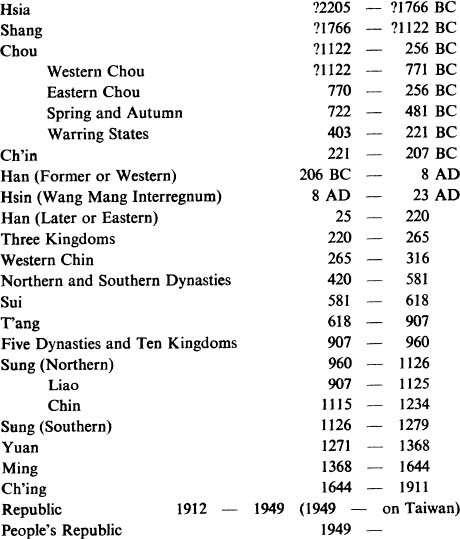

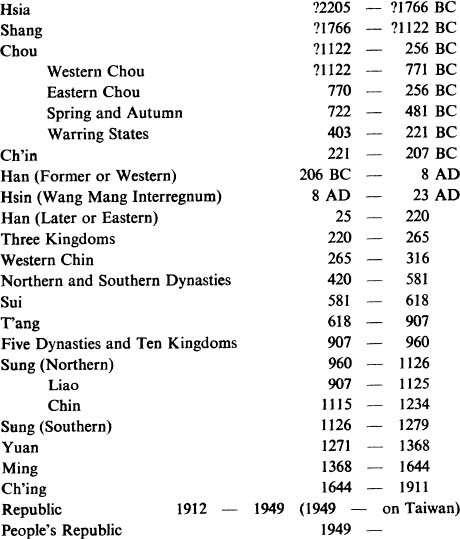

In time, entries range from pre-history to the end of 1977. They cover the classical pre-imperial period, the whole of the empire from 221 BC until its collapse in 1911, the short-lived Republic that succeeded it and the first twenty-eight years or so of the Peoples Republic. The bulk of the entries concern important personalities, dynasties and events, but some information is also given on historical trends, analytical concepts, social and economic history, and technology.

A book of this size can clearly contain only a fraction of the possible topics, and although I have attempted to select the most significant and most frequently encountered ones, I am very well aware of the number that have been left out. Inevitably certain periods and areas of study are treated more fully than others, but I hope that this corresponds to the needs of the general reader.

The importance of Chinese history cannot be overstated. In addition to providing the context for Chinese literature and the arts, it is vital to the understanding of China today. No country can possibly be more conscious of its heritage than China or be more deeply involved in its past. Many political campaigns in the Peoples Republic first make their appearance as historical controversies. The Cultural Revolution, for example, began with an academic argument about the merits of a 16th-century official, Hai Jui, and political argument in the early 1970s centred on a campaign to vilify Confucius.

Historians in other fields are increasingly coming to realise the comparative value of Chinese history, a history which provides both sharp contrasts with the European past and a surprising amount of common ground. I hope that this dictionary will help to make the comparison and the understanding of China and its history a little easier.

Romanisation Chinese is, of course, written in characters and there are a number of ways of representing the sounds of the words in Roman letters. The two most important systems are the Wade-Giles, which is rather old-fashioned but still widely used, and the Hanyu Pinyin which was developed in the Peoples Republic and is gradually replacing Wade-Giles. Many place names are romanised in neither of these but in the Post Office system, e.g.

Post Office | Peking |

Wade Giles | Pei-ching |

Hanyu Pinyin | Beijing |

In this Dictionary I have adopted the form most commonly found in English books, and cross-referred where necessary. This means that most names and terms appear in Wade-Giles which is still the most commonly used. Town and province names are likely to be in the Post Office form, and hardly anything is in Pinyin as this has not yet gained universal acceptance.

Alphabetical Order Different romanisations produce problems in alphabetical order. In this Dictionary hyphenated Chinese words, e.g. Ching-tien, are considered as one word, and apostrophes, e.g. Ching, Ching, are ignored for the purposes of alphabetical order.

Names Chinese people have a surname which comes first and is followed by a given name of which one individual may use severalchildhood name, family name, style, pseudonym. Names are entered here under the one by which individuals are most commonly known.

The names of emperors are even more complicated. They may be referred to by a family name, temple name, posthumous or tomb name or a reign title. Once again entries here are under the name most usually used in English. In practice, Ming and Ching emperors are referred to by their reign titles, e.g. Hung-wu, but earlier rulers are known by their posthumous titles, e.g. Tai-tsu.

Cross-References Cross-references have been kept to a minimum and (qv) only added where a further reference is likely to clarify. Individuals and events commonly known by different names are included under all the variations where possible. No cross-references are given for dynasties as nearly all are included, or for central figures such as Mao Tse-tung or Chiang Kai-shek.

Abbreviations The only abbreviations used throughout the Dictionary are CCP for Chinese Communist Party and KMT for Kuomintang (Nationalist Party). Other abbreviations have been used within a particular entry, e.g. APC for Agricultural Producers Co-operative, but these have been explained in the entry.

A

Abahai (15921643) Manchu leader and eighth son of Nurhachi. On the death of his father he was one of eight Banner princes, but he gradually concentrated power in his own hands. He extended the power of the Manchu state before the conquest of China by making Korea into a vassal state after attacking it in 1627 and 16367, and defeating the Inner Mongols in his expeditions into North China between 1629 and 1638. In 1636 he proclaimed the Ching Dynasty at Mukden, although it is usually dated from the collapse of the Ming house in 1644. His reign and particularly his relationship with the Chinese who surrendered to him laid firm foundations for the Ching dynasty.

Academia Sinica Founded in 1928 by the Nationalist Government to co-ordinate and advise on scientific affairs. Known in Chinese as the Central Research Academy (Chung-yang yen-chiu yuan) it included institutes specialising in the natural and social sciences and technology. After 1949 its name was changed to the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Chung-kuo ko-hsueh yuan) but it continued in its coordinating role operating over a hundred research institutes on behalf of the State Science and Technological Commission. The Academia Sinica continued on Taiwan after 1949.