2001, 2005 Alfredo Molano Bravo

Translation 2005 Daniel Bland

Foreword 2005 Aviva Chomsky

Introduction 2005 Lance Selfa

Appendix 2005 Mabel Gonzlez Bustelo

Originally published as Desterrados: crnicas del desarraigo by El ncora Editores, Colombia, 2001

This edition published in 2005 by Haymarket Books

P.O.Box 160185, Chicago, IL 60618, USA

www.haymarketbooks.org

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data:

Molano, Alfredo.

[Desterrados. English]

The dispossessed: chronicles of the desterrados of Colombia / Alfredo Molano.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-1-608463-15-2

1. Refugees--Colombia--Case studies. 2. Forced migration--Colombia--Case studies. 3. Refugee children--Colombia--Case studies. 4. Assassination--Colombia--Case studies. 5. Subversive activities--Colombia--Case studies. 6. Paramilitary forces--Colombia--Case studies. 7. Social conflict--Colombia--Case studies. I. Title.

HV640.5.C7M6513 2005

986.10635--dc22

Cover design by Ragina Johnson

Interior design and production by Ragina Johnson and David Whitehouse

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A Mnica Restrepo,

cuya risa derrota la muerte.

To Mnica Restrepo, whose

laugh triumphs over death.

Buenos das, memoria terca,

buenos das, sangre seca,

buenos das, hueso acostado.

buenos das, aire sin mano.

(Pensar en hacer burbujas

con el corazn ahogndose).

Jaime Sabines

Table of Contents

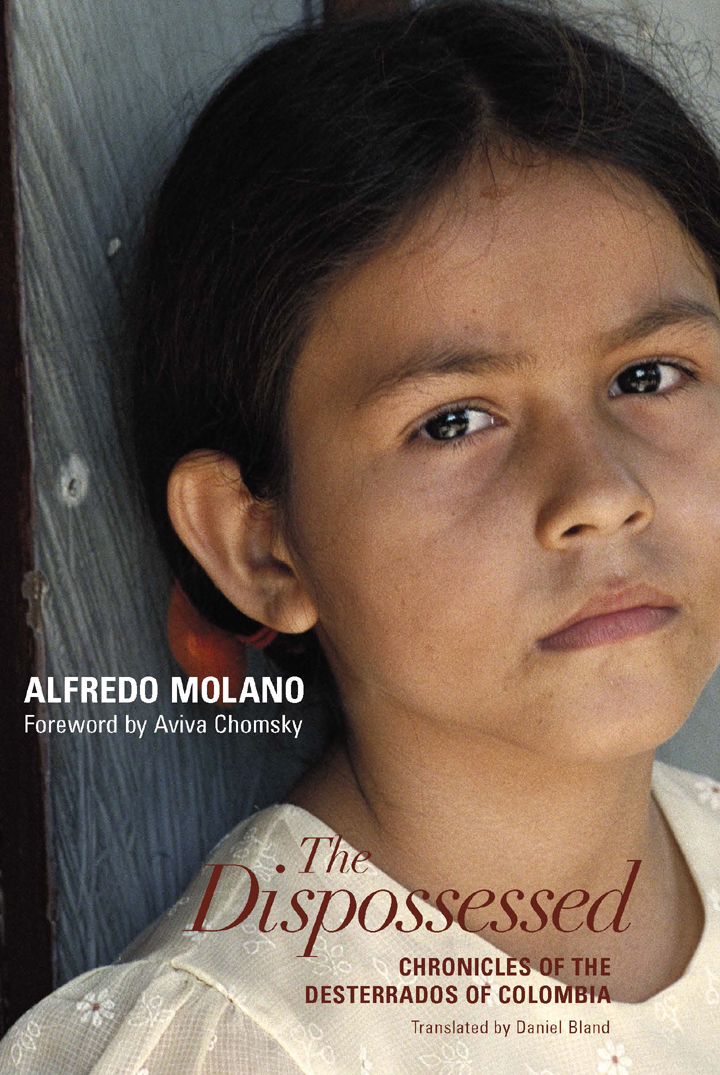

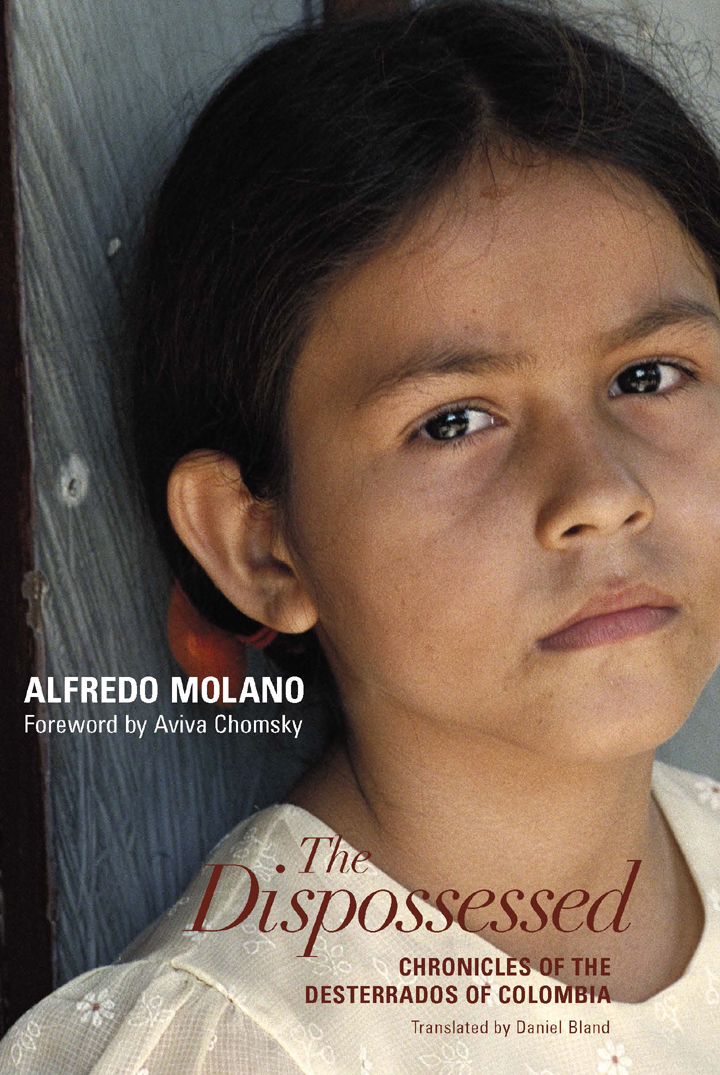

Cover photo

Oneida Bocanegra Pulido is eight years old. She was displaced from La Union Peneya, Caquet. Today, she lives in Florencia, Caquet, Colombia. Photograph courtesy Camilo George.

From Exile

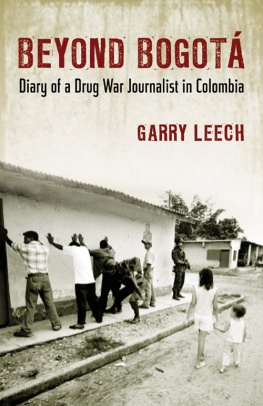

AUC paramilitaries in a jungle camp in southern Colombia, near the town of El Placer, Putamayo, in 2001. Photograph courtesy Daniel Bland.

The Defeat

This is Oneida (pictured on the cover), her cousin Margarita, and her grand mother. The three lived together in Union Peneya, in the Caquet region. On January 4, 2004, with the advance of the army during Operation Patriot, the FARC ordered the 1,500 townspeople to leave the area under penalty of death. Because Margarita was sick with a skin infection, the family could only hide under their beds while the guerrillas searched house to house. When the town was abandoned, the family could leave, but they had neither food nor medicine. The army evacuated the entire family at the end of January to Florencia, Caquet. Photograph courtesy Camilo George.

ngela

Survivors of the massacre at El Salado, a town of 4,500 inhabitants in the Montes de Maria area. On February 16, 2000, the town experienced one of the most horrific slaughters perpetrated by the paramilitaries who accused the townspeople of aiding the guerrillas. Over three days, 600 paramilitary fighters rounded up all the townspeople that they could take out of the jungleabout 500 people. For four days and nights, the captives were tortured, abused, and killed. One young woman who was gang-raped, had a piece of cactus forced down her throat, causing her to suffocate on her own blood. In the end, the paramilitaries painted anti-guerrilla slogans on houses with the blood of the victims. Photograph courtesy Camilo George.

Silences

U.S military-trained and -equipped Colombian army special antinarcotics commandos on patrol deep in the jungles of Colombia in search of cocaine processing laboratories. Photograph courtesy Steven Salisbury/Red Dot/Zuma Press.

The Turkish Boat

Thirteen-year-old Jhonn Nilson lives in the poor neighborhoods of San Jacinto, in Crdoba, where many survivors of the massacres in the Montes de Maria area fled. He looks through trash for nylon sacks so that his grandmother can make backpacks from their threads. They trade the backpacks for food at the San Jacinto market. Photograph courtesy Camilo George.

The Garden

Students at a school created by the residents of the La Ceiba neighborhood, in Carmen de Bolivar. This school was founded by a group of neighborhood residents to provide for the increasing number of displaced people that continue to arrive in the neighborhood from the conflict zones of Sucre, Cordoba, and Bolivar. This school has 300 students, but no running water. It is housed in two rooms and the hallway of a house. The students have neither textbooks nor school supplies. The usual breakfast in this school is a soft drink. Photograph courtesy Camilo George.

Osiris

Another survivor of the February 2000 El Salado massacre. Photograph courtesy Camilo George.

Nubia, La Catira

A relocated girl on a street in Bogot. Her sign says: I would like to study; my mother is unemployed; thank you for your help, as she asks drivers for money. Photograph courtesy Rodrigo Arangua/AFP.

By Aviva Chomsky

Most people in the United States know something about Colombia. Its difficult to live in this country and not absorb the idea that Colombia is a dangerous, violent place: a place full of guerrillas, cocaine, and drug traffickers.

Few people in the United States know that Colom bia is the third-largest recipient of U.S. military aid in the world; that more journalists, teachers, and trade unionists are killed every year in Colombia than anywhere else in the world; and that the perpetrators of the violence in Colombia are, overwhelmingly, the very military that the United States trains and suppliestogether with its paramilitary allies. Few know that the victims of the violence are, overwhelmingly, unarmed civilians, peasants, and workers, men, women, and children, whose crime is that their very presence stands in the way of the profits of the powerful.

Few people in the United States are aware of the global links in Colombias violence, yet these global links are many. Colombias coffee, oil, gold, bananas, flowers, emeralds, and coal, as well as Colombian cocaine, flow into world markets. Foreign companies such as Coca-Cola, Chiquita, Dole, Standard Oil, Occidental Petroleum, Exxon, Nestl, Drummond, BHP Billiton, Glencore, Anglo American, and GreyStar control important sectors of Colombias economy and reap important profits from their Colombian operations. International lending agencies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have pressed privatization on Colombia, meaning that the ability of the government to make decisions about the countrys resources and economy continues to shrink.

How can these companies maintain their profits when peasants live on the land the companies want to mine, when workers organize for decent wages and benefits, when citizens demand a voice in the use of their countrys resources? To answer this question is to uncover the sources of violence that are hidden to much of the U.S. public. Money flows from U.S. taxpayers to the U.S. government, to the Colombian military, to the paramilitaries; the latter two use these funds explicitly to remove any obstacles to the profits of foreign companies. Paramilitary incursions clear peasants from valuable land, such as the gold-rich areas of the Sur de Bolvar or Norte de Santander, opening it to foreign investors. Para military forces patrol companies premises, enter factories, and selectively kill workers who organize unions, as they have been accused of doing in the La Loma coal mine (owned by the Alabama-based Drummond Company), or Coca-Cola bottling plants, or Urabs banana plantations. Colombian army units are specially trained to guard U.S.-owned facilities like Occidental Petroleums Cao Limn-Coveas oil pipeline.