MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

San Tuathaigh, 2019

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117-681-8

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Incense

Somalia

you have to understand,

no one puts their children on a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

from Home, Warsan Shire

A teenage girl crouches over her clay stove outside the tent. She stirs the coals. They are red-hot, shimmering, like the rising sun that has dispersed grey twilight from the camp. In the distance, silhouetted, are the antennas and minarets of Mogadishu. All along the dusty street of tents, other women, in their many-coloured, multi-patterned hijabs, are nurturing lazy trunks of smoke.

Saadia stares into a rising ember; she is troubled by the dream she has just woken from. There had been a herd of goats, munching quietly in the sunset, when a great black beast had leapt among them, its mane trailing smoke, its claws glinting. She shudders and fans the fire again. The neighbourhood hums with chatter and gossip, but Saadia keeps to herself, yearning for solitude. It is found in focus: breakfast needs to be cooked. She places the pan over the flames and pours from a jug of mixture onto it, spiralling inwards to make a circle, which bubbles and steams, coalescing into a pancake canjeero. Soon there is a stack of them.

Inside, under a billowing ceiling, her family sits around on rugs and cushions, passing teapots about, filling cups to wash down their meal of canjeero, bananas and sugar, drizzled with sesame oil. Saadia is the eldest child; she has two brothers and five sisters. Her mother rubs sleep from the baby girls eyes, while her father hurries the other children.

Eat up! You will be late!

When breakfast is eaten, the tent empties. The younger children trudge off to Quranic school, the older ones zip outside to their friends, and Saadias father shuffles across to the neighbours, to speak and smoke. There are no jobs. Saadia and her mother tidy away the bowls and cups and sweep the floor.

We will have fish for lunch, her mother says, lighting some incense.

Yes, Hooyo.

Get some tuna, the usual amount. She digs in her purse. Here you go.

Saadia takes the shillings, nodding.

What has come over you, Saadia? You are very quiet this morning.

Saadia pauses. She wants to blurt out her nightmare, to tell of the vicious creature, of its knife-like teeth and the mangled kids scattered about the meadow. She wants to explain the sounds she heard: bleating, shrieking and then silence a deep, immutable silence. But she does not, she just smiles.

Its nothing, Hooyo, just a dream. Ill tell you about it later.

Her mother tuts good-humouredly and rubs her shoulder.

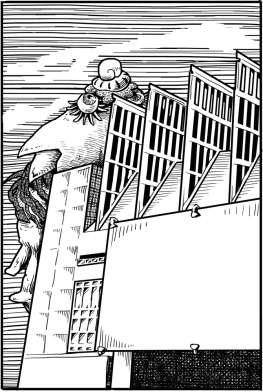

Saadia clings to the handrail as the bus jolts into another pothole. It is packed and sweaty; morning rush hour is in full flow. Outside, the tents and trees give way to huts and then to multi-storey buildings. The bus navigates around craters and chunks of masonry, and frequently jerks to a halt in the traffic: donkey drays, handcarts, the occasional car rattling past.

The scars of war are all around. Bullet holes spatter every edifice like a pox, and the crumbling, undulating parapets above grin and gape like the lower jawbones of so many skulls. There are gaps where entire buildings have collapsed: weeds and scrub tangling upon heaps of debris.

Saadia came into the world in 1991, just as the Somali government was prodded out of it. She is unversed in the workings of a stable society. Sprawling graffiti proclaims the ascendancy of warlords and factions who vie with each other unceasingly. There are periods of tense truce that collapse suddenly into skirmishes. Then the dust settles and life resumes with shifted alliances, new boundaries and, inevitably, the haunting laments of mothers.

Checkpoints occur along the borders of these tectonic polities, each exacting a toll from those who would pass through. Saadias bus pays two along the way. Sometimes, a gang of boys with no education or employment to offer hope will set up their own roadblock and demand their slice, aping the militiamen. They cannot be scolded or mocked: very often they will be strutting about with impossibly long assault rifles slung from their skinny shoulders. For some this will be a boyish experiment, a boisterous phase with lessons learned. For too many, however, it is an apprenticeship into a life by the sword.

The bus shudders to a halt. Saadia keeps her hand pressed against her purse as she steps out onto the street, though it is well buried in the folds of her dress. She emerges into a jostling shoal: women surge around her carrying bags and baskets; a scooter darts through with a shark balancing and bouncing behind the driver; young lads, sons or nephews of fishermen, plod with swordfish as big as themselves across their shoulders, and above all this looms a building squint-inducing in its whiteness the length of the block, with high, semi-circular windows. It is a miracle the arcade has survived at all, but somehow it has weathered almost two decades of deadly hail: mortars, rockets, grenades. Today, thankfully, only seagulls fly overhead.

The whiteness of the fish market is almost ghostly among the other tattered buildings. It is a visitation from an earlier time, an era Saadia has only heard talked about among elders. On a wrinkled postcard she once saw it: a splendid city on the sea, of white cubes and domes The Pearl of the Indian Ocean they had called it, when Somalia had been a paragon of peaceful decolonisation. Saadia finds this difficult to imagine; it is somewhat improbable, falling into the realm of mythology.

She gazes down the street while queueing to enter the fish market. She would like to forget about her chores for a minute or an hour and stroll down to where the sturdy fisherboys are streaming, to weave through the ruins and out onto the waterfront, where the stench of aquatic entrails is breezed away and the jetty swerves far into the ocean. Those murmuring waters do not retain bullet holes, they do not permit graffiti. She longs to sit by the waters edge, with her back to the crumbling roofscape, to let her feet splash and watch the blue turn to lavender, pink, orange, red; she longs for her shadow to stretch towards the horizon and for the stars to peek out one at a time. She considers it, but then the queue lurches forward into the shadows of the arcade. There is food to secure and it is unwise for a young woman to wander solo in this city.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.mercierpress.ie www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks www.facebook.com/mercier.press

www.facebook.com/mercier.press