Heath - Aristarchus of Samos

Here you can read online Heath - Aristarchus of Samos full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1981, publisher: Dover Publications, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Aristarchus of Samos

- Author:

- Publisher:Dover Publications

- Genre:

- Year:1981

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Aristarchus of Samos: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Aristarchus of Samos" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Aristarchus of Samos — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Aristarchus of Samos" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

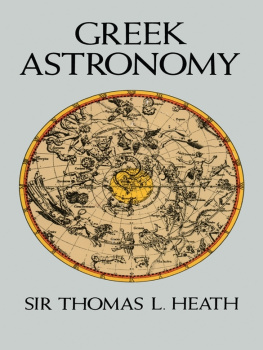

ARISTARCHUS

OF SAMOS

THE ANCIENT COPERNICUS

OF SAMOS

THE ANCIENT COPERNICUS

Sir Thomas Heath

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1981 and republished in 2004, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1913 by the Clarendon Press, Oxford, under the title Aristarchus of Samos, the Ancient Copernicus; a History of Greek Astronomy to Aristarchus, Together with Aristarchuss Treatise on the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon, a Greek Text with Translation and Notes by Sir Thomas Heath. The Dover edition is published by special arrangement with Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heath, Thomas Little, Sir, 18611940.

Aristarchus of Samos, the ancient Copernicus / Sir Thomas Heath.

p. cm.

Originally published: Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1913.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-15081-9

1. Astronomy, Greek. 2. AstronomersGreeceBiography. 3. Aristarchus, of Samos. 4. Aristarchus, of Samos. On the sizes and distances of the sun and moon. I. Aristarchus, of Samos. On the sizes and distances of the sun and moon. English & Greek. II. Title.

QB21.H38 2004

520.92dc22

2004058241

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

THIS work owes its inception to a desire expressed to me by my old schoolfellow Professor H. H. Turner for a translation of Aristarchuss extant work On the sizes and distances of the Sun and Moon. Incidentally Professor Turner asked whether any light could be thrown on the grossly excessive estimate of 2 for the angular diameter of the sun and moon which is one of the fundamental assumptions at the beginning of the book. I remembered that Archimedes distinctly says in his Psammites or Sand-reckoner that Aristarchus was the first to discover that the apparent diameter of the sun is about 1/720th part of the complete circle described by it in the daily rotation, or, in other words, that the angular diameter is about  , which is very near the truth. The difference suggested that the treatise of Aristarchus which we possess was an early work; but it was still necessary to search the history of Greek astronomy for any estimates by older astronomers that might be on record, with a view to tracing, if possible, the origin of the figure of 2.

, which is very near the truth. The difference suggested that the treatise of Aristarchus which we possess was an early work; but it was still necessary to search the history of Greek astronomy for any estimates by older astronomers that might be on record, with a view to tracing, if possible, the origin of the figure of 2.

Again, our treatise does not contain any suggestion of any but the geocentric view of the universe, whereas Archimedes tells us that Aristarchus wrote a book of hypotheses, one of which was that the sun and the fixed stars remain unmoved and that the earth revolves round the sun in the circumference of a circle. Now Archimedes was a younger contemporary of Aristarchus; he must have seen the book of hypotheses in question, and we could have no better evidence for attributing to Aristarchus the first enunciation of the Copernican hypothesis. The matter might have rested there but for the fact that in recent years (1898) Schiaparelli, an authority always to be mentioned with profound respect, has maintained that it was not after all Aristarchus, but Heraclides of Pontus, who first put forward the heliocentric hypothesis. Schiaparelli, whose two papers Le sfere omocentriche di Eudosso, di Callippo e di Aristotele and I precursori di Copernico nell antichit are classics, showed in the latter paper that Heraclides discovered that the planets Venus and Mercury revolve round the sun, like satellites, as well as that the earth rotates about its own axis in about twenty-four hours. In his later paper of 1898 (Origine del sistema planetario eliocentrico presso i Greci) Schiaparelli went further and suggested that Heraclides must have arrived at the same conclusion about the superior planets as about Venus and Mercury, and would therefore hold that all alike revolved round the sun, while the sun with the planets moving in their orbits about it revolved bodily round the earth as centre in a year; in other words, according to Schiaparelli, Heraclides was probably the inventor of the system known as that of Tycho Brahe, or was acquainted with it and adopted it if it was invented by some contemporary and not by himself. So far it may be admitted that Schiaparelli has made out a plausible case; but when, in the same paper, he goes further and credits Heraclides with having originated the Copernican hypothesis also, he takes up much more doubtful ground. At the same time it was clear that his arguments were entitled to the most careful consideration, and this again necessitated research in the earlier history of Greek astronomy with the view of tracing every step in the progress towards the true Copernican theory. The first to substitute another centre for the earth in the celestial system were the Pythagoreans, who made the earth, like the sun, moon, and planets, revolve round the central fire; and, when once my study of the subject had been carried back so far, it seemed to me that the most fitting introduction to Aristarchus would be a sketch of the whole history of Greek astronomy up to his time. As regards the newest claim made by Schiaparelli on behalf of Heraclides of Pontus, I hope I have shown that the case is not made out, and that there is still no reason to doubt the unanimous testimony of antiquity that Aristarchus was the real originator of the Copernican hypothesis.

In the century following Copernicus no doubt was felt as to identifying Aristarchus with the latter hypothesis. Libert Fromond, Professor of Theology at the University of Louvain, who tried to refute it, called his work Anti-Aristarchus (Antwerp, 1631). In 1644 Roberval took up the cudgels for Copernicus in a book the full title of which is Aristarchi Samii de mundi systemate partibus et motibus eiusdem libellus. Adiectae sunt . P. de Roberval, Mathem. Scient, in Collegio Regio Franciae Professoris, notae in eundem libellum. It does not appear that experts were ever deceived by this title, although Baillet (Jugemens des Savans) complained of such disguises and would have had Roberval call his work Aristarchus Gallus, the French Aristarchus, after the manner of Vietas Apollonius Gallus and Snelliuss Eratosthenes Batavus. But there was every excuse for Roberval. The times were dangerous. Only eleven years before seven Cardinals had forced Galilei to abjure his errors and heresies; what wonder then that Roberval should take the precaution of publishing his views under another name?

Voltaire, as is well known, went sadly wrong over Aristarchus (Dictionnaire Philosophique, s.v. Systme). He said that Aristarchus is so obscure that Wallis was obliged to annotate him from one end to the other, in the effort to make him intelligible, and further that it was very doubtful whether the book attributed to Aristarchus was really by him. Voltaire (misled, it is true, by a wrong reading in a passage of Plutarch, De facie in orbe lunae, c. 6) goes on to question whether Aristarchus had ever propounded the heliocentric hypothesis; and it is clear that the treatise which he regarded as suspect was Robervals book, and that he confused this with the genuine work edited by Wallis. Nor could he have looked at the latter treatise in any but a very superficial way, or he would have seen that it is not in the least obscure, and that the commentary of Wallis is no more elaborate than would ordinarily be expected of an editor bringing out for the first time, with the aid of MSS. not of the best, a Greek text and translation of a mathematical treatise in which a number of geometrical propositions are assumed without proof and therefore require some elucidation.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Aristarchus of Samos»

Look at similar books to Aristarchus of Samos. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Aristarchus of Samos and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.