Thomas L. Heath - Greek Astronomy

Here you can read online Thomas L. Heath - Greek Astronomy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Dover Publications, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Greek Astronomy

- Author:

- Publisher:Dover Publications

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greek Astronomy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Greek Astronomy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Greek Astronomy — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Greek Astronomy" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

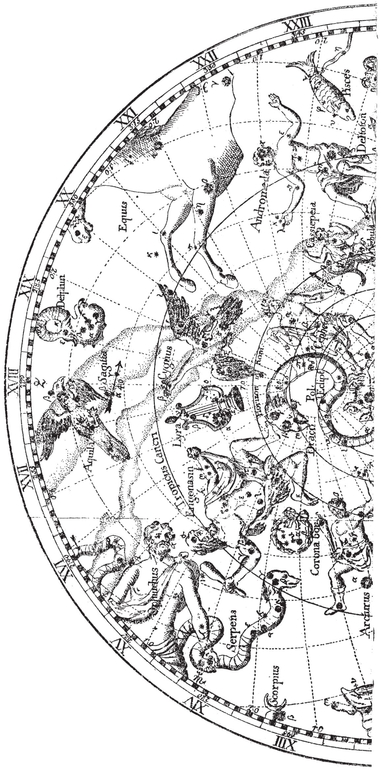

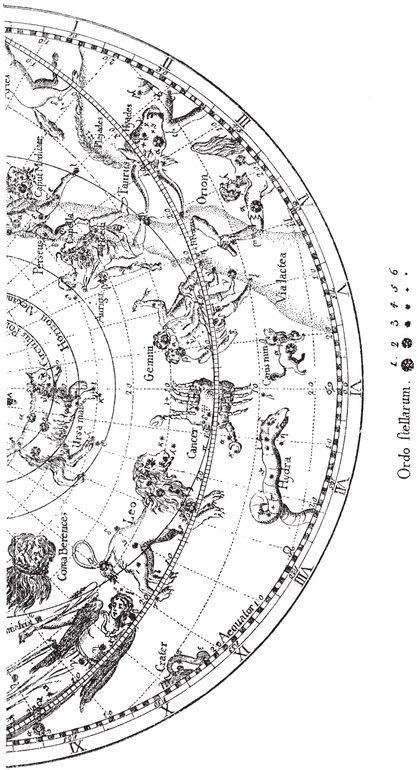

HEMISPHAERIUM BOREALE

PLATO, Theaetetus, 174 A.

A CASE in point is that of Thales, who, when he was star-gazing and looking upward, fell into a well, and was rallied (so it is said) by a clever and pretty maidservant from Thrace because he was eager to know what went on in the heaven, but did not notice what was in front of him, nay, at his very feet.

HERODOTUS, I, 74.

When, in the sixth year, they [the Lydians and the Medes] encountered one another, it so fell out that, after they had joined battle, the day suddenly turned into night. Now that this transformation of day (into night) would occur was foretold to the Ionians by Thales of Miletus, who fixed as the limit of time this very year in which the change actually took place.

CLEMENT OF ALEXANDRIA, Stromat. I, 65.

Eudemus observes in his History of Astronomy that Thales predicted the eclipse of the sun which took place at the time when the Medes and the Lydians engaged in battle, the King of the Medes being Cyaxares, the father of Astyages, and the King of the Lydians being Alyattes, the son of Croesus; and the time was about the fiftieth Olympiad [580577 B.C.]. (But cf. Pliny, N. H., c. 12, 53: Among the Greeks Thales was the first of all men to investigate (the cause of eclipses), in the fourth year of the forty-eighth Olympiad [585/4 B.C.], he having predicted an eclipse of the sun which took place in the reign of Alyattes in the year 170 A.U.C.)

THEON OF SMYRNA, p. 198.

Eudemus relates in his Astronomies... that Thales was the first to discover the eclipse of the sun, and the fact that the suns period with respect to the solstices is not always the same.

DIOGENES LARTlUS, I, 24.

Thales was the first to discover the length of the interval from solstice to solstice.

ARISTOTLE, Metaph. A. 3, 983 b 202.

Thales, the originator of this kind of philosophical inquiry [i.e. the search for one material cause of all things], says that water is the first principle (this is why he also declared that the earth rests on water).

DIOGENES LARTlUS, I, 27.

Thales laid it down that the first principle of all things is water, and that the universe is animate and full of gods. They say too that he discovered the seasons of the year, and divided the year into 365 days.

HERODOTUS, II, 4.

It is said that the Egyptians were the first of all men to discover the year, to which they gave twelve parts

(months) making up the (four) seasons. And herein the Egyptians reckon, as it seems to me, more sensibly than the Greeks, in so far as the Greeks put in an intercalary month every third year to keep the seasons right, whereas the Egyptians reckon their twelve months at thirty days each and add in every year five days outside the number (of twelve times thirty).

DIOGENES LARTIUS, I, 23.

Callimachus knows him (Thales) to be the discoverer of the Little Bear, for he says in his lambi that he was said to have marked ( lit. measured) the stars of the Wain, by which the Phoenicians sail.

SIMPLICIUS, in Phys. Aristotelis, p. 24, 13, Diels.

ANAXIMANDER of Miletus, who was a fellow-citizen and friend of Thales, said that the first principle (i.e. material cause) and element of existing things is the Infinite, and he was the first to introduce this name for the first principle. He maintains that it is neither water nor any other of the so-called elements, but another sort of substance which is infinite, and from which all the heavens and the worlds in them are produced; and into that from which existent things arise they pass away once more, as is ordained; for they must pay the penalty and make reparation to one another for the injustice they have committed, according to the sequence of time, as he says in these somewhat poetical terms.

PSEUDO-PLUTARCH, Stromat. 2.

Anaximander said that the Infinite contains the whole cause of the generation and destruction of the All; it is from the Infinite that the heavens are separated off, and generally all the worlds, which are infinite in number. He declared that destruction and, long before that, generation have been going on from infinitely distant ages, all the worlds recurring in cycles.

HIPPOLYTUS, Refutation of all Heresies, I, 6.

He says that this [the Infinite] is eternal and ageless and embraces all the worlds. And he implies the existence of time in that the three stages of coming into being, existence, and passing-away are distinguished.... And besides the Infinite he says there is eternal motion, in the course of which it happens that the heavens come into being.

HERMIAS, Irrisio, 10.

Anaximander says eternal motion is a principle older than the moist, and it is by this eternal motion that some things are generated and others destroyed.

ATIUS, De placitis, I, 3, 3.

He says that the first principle (or material cause) is infinite, in order that the process of coming into being which is set up may not suffer any check.

SIMPLICIUS, on De caelo, p. 615, 13, Heiberg.

Anaximander was the first to assume the Infinite as first principle, in order that he might have it available for his new births without stint.

SIMPLICIUS, in Phys. p. 1121, 5.

Those who assumed that the worlds are infinite in number, as did Anaximander, Leucippus, Democritus, and, in later days, Epicurus, assumed that they also came into being and passed away, ad infinitum, there being always some worlds coming into being and others passing away; and they maintained that motion is eternal: for without motion there is no coming into being or passing away.

PSEUDO-PLUTARCH, Stromat. 2.

Anaximander says that that which is capable of begetting the hot and the cold out of the eternal was separated off during the coming into being of our world, and from this there was produced a sort of sphere of flame which grew round the air about the earth as the bark round a tree; then this sphere was torn off and became enclosed in certain circles or rings, and thus were formed the sun, the moon, and the stars.

HIPPOLYTUS, Refut. I, 6, 4, 5.

The stars are produced as a circle of fire, separated off from the fire in the universe and enclosed by air. They have as vents certain pipe-shaped passages at which the stars are seen; hence, when the vents are stopped up, eclipses take place. The moon appears sometimes as waxing, sometimes as waning, to an extent corresponding to the closing or opening of the passages.

ATIUS, II, 13, 7.

The stars are compressed portions of air, in the shape of wheels filled with fire, and they emit flames at some point from small openings.

HIPPOLYTUS, loc. cit.

The earth is poised aloft, supported by nothing, and remains where it is because of its equidistance from all other things. Its form is rounded, circular, like a stone pillar; of its plane surfaces one is that on which we stand, the other is opposite.

PSEUDO-PLUTARCH, Stromat. 2.

The earth, he says, is cylinder-shaped and its depth is such as to have a ratio of one-third to its breadth.

HIPPOLYTUS, Refut. I, 6, 5.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Greek Astronomy»

Look at similar books to Greek Astronomy. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Greek Astronomy and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Thomas T. Arny - Explorations: Introduction to Astronomy [9 ed.]](/uploads/posts/book/143658/thumbs/thomas-t-arny-explorations-introduction-to.jpg)