2020 Robert P. Watson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for third-party websites or their content. URL links were active at time of publication.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Watson, Robert P., 1962 author.

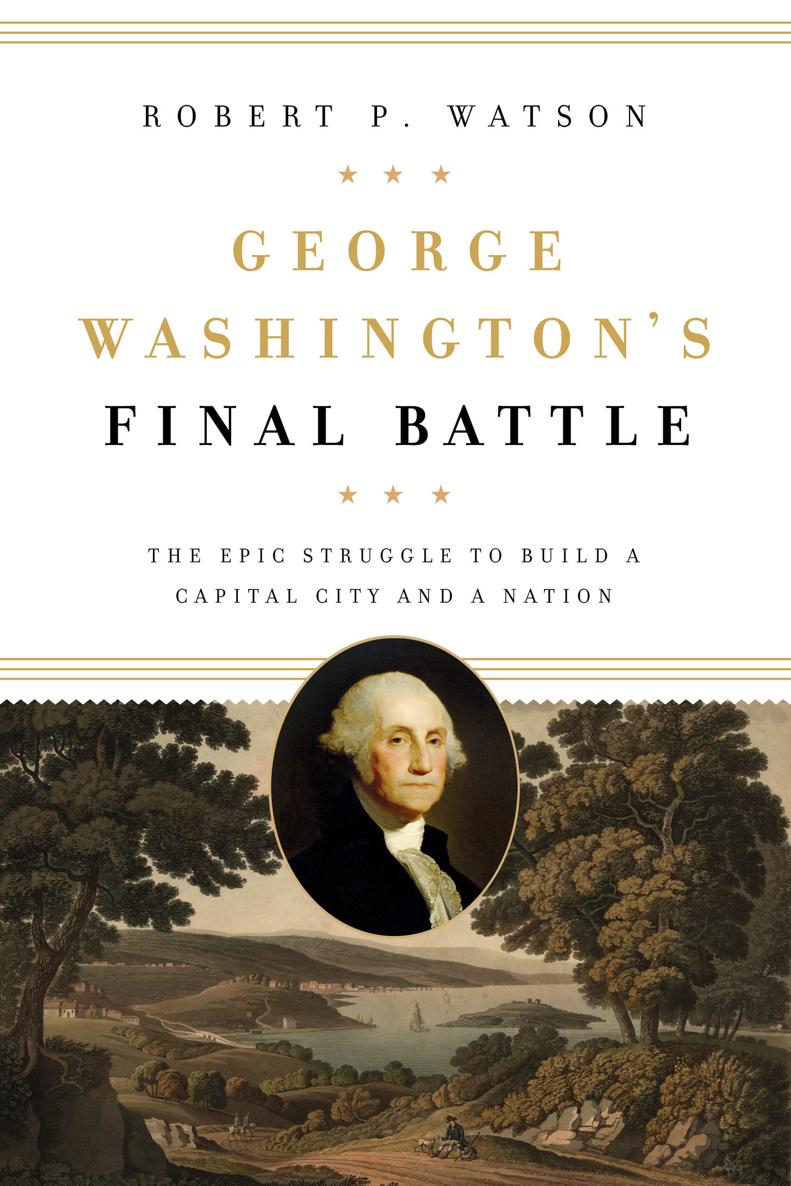

Title: George Washingtons Final Battle : The Epic Struggle to Build a Capital City and a Nation / Robert P. Watson.

Description: Washington, DC : Georgetown University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019032707 (print) | LCCN 2019032708 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626167841 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781626167858 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Washington, George, 17321799. | City planningWashington (D.C.)History18th century. | Washington (D.C.)History18th century. | United StatesCapital and capitolHistory.

Classification: LCC F197 .W315 2020 (print) | LCC F197 (ebook) | DDC 973.4/1092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032707

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032708

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

212098765432First printing

Printed in the United States of America.

Jacket design by Jeff Miller, Faceout Studio.

Cover images:

Cartwright, T., Artist, and George Beck. George Town and Federal City, or City of Washington. Georgetown Washington D.C, 1801. London and Philadelphia: Atkins & Nightingale. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002695146/.

Royalty-free stock illustration ID: 423235858 George Washington, by Gilbert Stuart, c. 180305, American painting, oil on canvas.

Washington and Hoban inspect DC, 1798 by N. C. Wyeth, 1932.

Courtesy of the White House Historical Association.

A great city would really and absolutely be raised up, as if by magic.

Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, 1789

PREFACE

Millions of Americans and tourists from all around the world enjoy visiting the city named for George Washington. The majestic governmental buildings, tree-lined National Mall, world-famous museums and galleries, touching memorials, and imposing monuments are sites to behold. Indeed, the federal government has certainly done a commendable job preserving its history, commemorating the wars and events that shaped the nation, and celebrating the countrys heroes. Today the city is full of splendor, but this was not always the case.

The remarkable events and political struggles that led to the creation of a national capital are not well-known. Rather, the founding debates about the citys location, design, and size, along with the numerous challenges of building an entirely new city out of what some early visitors called a wilderness, are often omitted from the pages of textbooks, at times ignored by scholars, and generally taken for granted by the American public. Yet these very same issues proved even more contentious for the founders than the debates at the Constitutional Convention over a system of governance. In fact, on several occasions, these other founding debates nearly tore the young nation apart.

General Washington emerged victorious from the Revolutionary War and was the fledgling republics most revered citizen. After the long conflict he looked forward to a quiet retirement from public life and domestic tranquility under vine and fig tree, but his work was not done. The new experiment in popular government for which he had shed blood was a work in progress. Indeed, it was on shaky groundbitterly divided, in debt, and paralyzed by a weak, ineffectual, and ad hoc system of governance.

Washington would need every bit of his considerable esteem and surprising political shrewdness after the war to convince his peers that a grand capital city was necessaryand then enlist them in building such a capital. He understood that it was not simply a matter of building a city. The general and his fellow founders were proposing an entirely new form of government based on radical ideas whereby the people would lead. Thus, the location and design of the capital mattered; they would shape the development of the nation politically and economically. Building the capital would therefore be an exercise in building the republic.

Washington hoped the city would imbue his fellow citizens with a sense of nationhood and American identity while also uniting the raucous states behind an energetic and stable federal government. The city would therefore help forge a political culture of democracy and both reflect and host the lofty ideals of self-government. It would not be easy.

A note to the reader on spelling and word use: when quoting letters and other historic documents, the original spelling and grammar are retained wherever and whenever possible. Only in a few instances have changes or corrections been made, and only when the meaning of the original writing might be unclear. In addition, during the founding period, political factions emerged that would soon form the nations first political parties. The federalists and anti-federalists played a central role in many of the important debates and developments discussed in this book. As political parties they were also known by other names. For instance, the anti-federalists became the Jeffersonian Republicans, a precursor to the Democratic-Republican Party, which may sound quite confusing to us today. The federalists retained their name for several years until the party faded into the pages of history. To uncomplicate the matter, the terms federalist and anti-federalist are written in lowercase when referring to political movements and factions. When political parties formed, the terms are capitalized, and the names of the nascent parties are used.

One additional clarification: even though the historian Kenneth Bowling notes in his book Peter Charles LEnfant that the famous French architect used the name Peter while in America, this book will use Pierre because most people know him by that name and most sources use his French name, which was his birth name. The goal here is to avoid confusion while still being historically accurate.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.