Contents

Page List

Guide

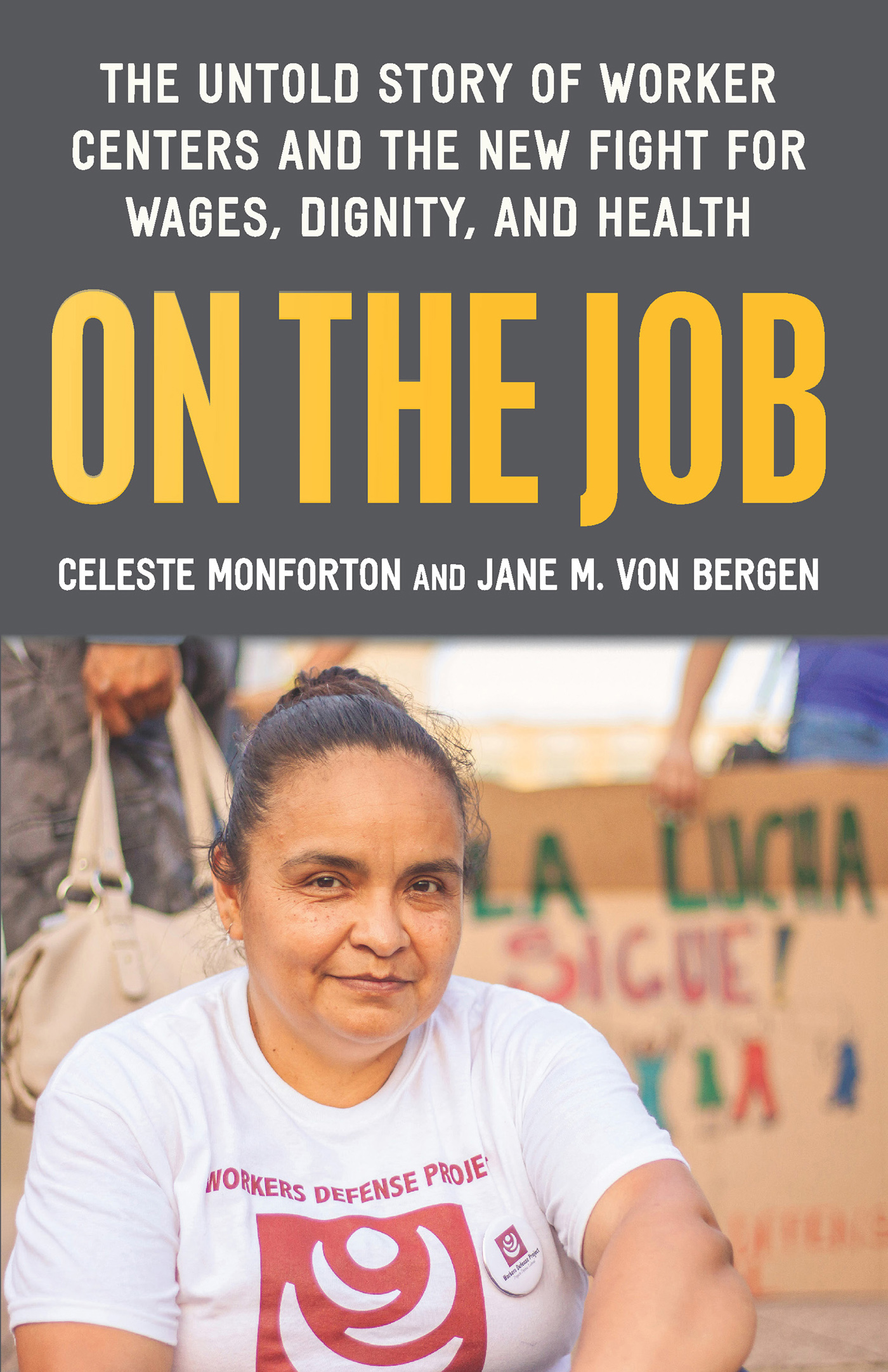

ON THE JOB

ON THE JOB

The Untold Story of Worker Centers and the New Fight for Wages, Dignity, and Health

CELESTE MONFORTON

AND

JANE M. VON BERGEN

CONTENTS

ON THE JOB

New Labor members pose for a photo after an April 2019 training, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Jane M. Von Bergen

INTRODUCTION: AWAKENING THE POWER

T he International Workers Day 2020 protest outside a medical supply manufacturing plant on the north side of Chicago wasnt exactly a made-for-television moment. Although news crews did show up at the appointed time, they didnt get the usual footage of workers with arms linked, hands clasped, and banners aloft.

Instead, each protesting worker was standing six feet apart, all isolated icons of determination in the nearly empty parking lot next to an almost-traffic-less roadway.

On May 1, 2020, as the United States and nations around the world staggered under the strain of a coronavirus pandemic, workers protests took on a different lookmasks and separation to slow the contagion. By that day, the COVID-19 virus had already killed 250,000 worldwide, 3.7 million cases had been reported, and the U.S. death toll had exceeded 60,000.

When the pandemic struck the United States suddenly and fiercely in mid-March, many low-wage workers found themselves forced into one of two bad situations. Either they had lost their jobs and faced nearly immediate financial disaster, or else they had kept their jobs, often working in unsafe situations, with the prospect of sickness or death.

Having to choose among bad situations is nothing new for the 60 million Americans who are paid too little for their labor yet fuel a huge share of the economy. They provide the kind of goods and services that allow the rest of us to devote ourselves to career and family. The health and financial crises created by COVID-19 only exacerbated the inequities they already experience.

Thats how it felt to the workers demonstrating outside the LSL Healthcare factory in Chicago. But they didnt have to act alone. They were supported by Arise Chicago, one of the countrys 225 worker centers. The community labor organization helped the workers draft their demand letter to the company president and present it while news cameras were rolling. The workers who signed the letterthirty-five in allwere now part of the nationwide worker center movement.

Over the last two decades, worker centers had cultivated enough community trust for workers to know where they could turn for support when the virus struck. The centers could help workers access food or rent assistance, resolve unsafe workplace situations, and, importantly, organize for broader protections such as paid leave.

Making an appeal to an employer for safer jobs and fair pay is a risky proposition under any circumstances. But Arise Chicago and other worker centers across the United States have been helping workers experience the power of collective action. They create a safe space for workers to weigh the risks and to strategize the best approaches to demanding improvements on the job. These community labor organizations provide an environment where community members can learn and develop their organizing and leadership skills.

Worker centers have taken root in small towns, like Morganton, North Carolina; Bryan, Texas, and Graton, California. In some of the biggest U.S. cities, there may be five or ten worker centers, each one with its own personality, mission, and history. Worker centers gather marginalized workersmarginalized because of language, because of immigration status, because their jobs as domestic workers isolate them, or because their employment status is murky as gig or temp agency workers.

Some worker centers have members who work in one industry, such as in poultry production or garment fabrication. Some centers focus exclusively on employment problems; others branch out to assist with immigration issues, finding that they are part and parcel of problems on the job.

What worker centers have in common is a sense of community built through shared experiencesshared experiences on the job, shared experiences on life journeys, or, perhaps, shared experiences adjusting to a new land. What they also have in common is a sense of struggle for higher wages (or any wages), a safer place to work, and a better life.

On the Job: The Untold Story of Worker Centers and the New Fight for Wages, Dignity, and Health focuses on this little-known part of todays labor movement. Its about workers forced to organize for the most basic on-the-job fundamentals: the wages for which theyve worked, short rest breaks from labor, and the simple ability to use the bathroom when nature calls.

Worker centers are part of the centuries-long struggle by workers to gain, as the old labor song says, both bread and rosessustenance and satisfaction. In its simplest form, the labor movement is two or three employees complaining about their boss or their working conditions and then, together, taking some action to improve their situations. On the other end are mass strikes and protests, like the December 2019 pension protest that shut down subways in Paris. In between is what most people think of as labortraditional unions with collective bargaining agreements, officers, budgets, and headquarters.

Somewhere between the two or three people taking on their bosses and the traditional union is what is known as a worker center. Worker centers draw inspiration from pre-union community-expressions of working peoples organizations such as mutual aid societies or, in Chicago, settlement houses, explained Adam Kader, director of Arise Chicago Worker Center. And then, interestingly, labor unions are beginning to take inspiration from us.

To illustrate, Kader refers to the Fight for $15 campaign to support fast-food workers that was organized beginning in 2012 by the Service Employees International Union. Everything they were doing was from the playbook of worker centers. You might have three out of twenty workers in a McDonalds who would stage a walkout. These are job-placed actions, with community supporters, with a public component, with allies and politicians and media. Labor unions are now looking to worker center tactics for their renewal and their organizing strategies, Kader said.

We understand the labor movement as encompassing organized unionized workers and unorganized non-union workers, he continued. Youll hear some young worker center types saying things like Unions are old hat and were the new wave. We strongly disagree with that. We believe that worker centers are a recent evolution of the labor movement, but the future of the labor movement includes both.

The COVID-19 pandemic, with life and death in the balance, became a crucible for both worker centers and their members. Never were they more challenged, and never were the challenges more urgent. Some worker centers members are live-in nannies and housekeepers who were fired by their employers, losing homes and jobs in one day. Others are warehouse temp workers, deemed essential, but not essential enough to be provided with protective masks. Some are intimate caregivers in nursing homes or private houses, facing the very real possibility of bringing the virus back to their own families. Others labor in meat and poultry plants, standing just a few feet apart, in danger of contagion.