To my mother, Marybeth Weston, who lived to see this book completed, but not published,

And to my wife, Linda Richichi, who has given me so much love.

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2016 Mark Weston

Map of United States of America with States: Outline by FreeVectorMaps.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4930-2257-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-2258-8 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

INTRODUCTION

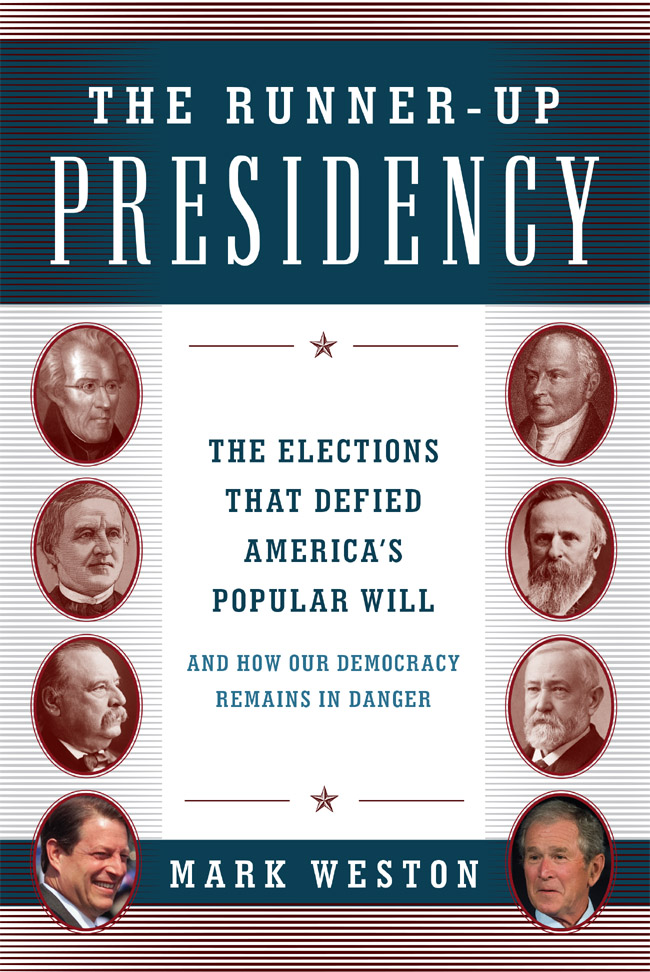

Electoral Votes: A Risky Game of Dice

WHEN GEORGE W. BUSH WON THE PRESIDENCY IN 2000 WITH NEARLY 544,000 fewer votes than Al Gore, it was not a fluke. Runner-up candidates became president in 1876 and 1888, and the real surprise is that it took 112 years for this to happen again. Another second-place candidate will probably win the presidency soonand this time, the outrage will be greater because the public will not see the elections outcome as a rare mishap, but as the product of a flawed political system.

In fact, we nearly had a second-place president in 2012. Because of Bushs victory in 2000, most people think that our electoral system is biased toward the Republicans. But if Mitt Romney had won 2% more of the popular vote in every state in 2012, and President Obama had won 2% less, then Obama would have been a runner-up president in his second term, just as President Bush was in his first term. With the extra votes, Romney would have won the nations popular vote and taken Florida, Virginia, and Ohio, but President Obama would still have won the other northern swing states, and with them, the electoral vote, 272 to 266.

Are conservatives angry now? Imagine their wrath if President Obama had been reelected president with fewer popular votes than Mitt Romney. And think of the fury Democrats will feel if a Republican runner-up is elected again. Most Democrats accepted the result of the 2000 election when the Supreme Court stopped Floridas recount, but many still have bitter feelings about it.

If a Republican with fewer popular votes than his or her opponent is elected again, the anger repressed since 2000 could poison the political climate. Democrats may be far less willing than before to concede the legitimacy of a second Republican runner-up president. If our democracy does not seem to be working, massive demonstrations and even civil disobedience could become common.

Both here and abroad, people would question whether America is truly a democracy or just pretending to be one. Diplomats serving the next second-place president would have a hard time lecturing dictators about human rights if at home the most basic right of being able to choose ones leader were in question.

In 2000, even though a half a million more people voted for Gore than Bush, the public accepted Bushs victory calmly. First, the 9/11 attacks occurred less than eight months after President Bushs inauguration, confirming his authority as Commander in Chief in a way that the election never had. Patriotism set aside the lingering doubt about Bushs legitimacy.

Second, and more important, the public believed that the 2000 elections strange outcome was a once-in-a-century oddity. America had not elected a runner-up president since 1888when the Republican nominee, Benjamin Harrison, defeated the Democratic incumbent president, Grover Cleveland, with 90,000 fewer votes. Most Americans continue to assume that nothing like this will happen again for another hundred years.

During a series of close elections, however, a runner-up president is a probability, not a rarity. After 1876, for example, when the Republican runner-up candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, defeated the Democratic popular-vote winner, Samuel Tilden, it took only 12 years for another second-place candidate, Benjamin Harrison, to be elected president. Two flukes in just 12 years.

In our own time, if the next runner-up president is a Democrat (so that Republicans and Democrats will have both shared the pain of feeling cheated by the electoral system), the result might be a rush to replace the electoral system with something new and ill-advised, with unintended and unfortunate consequences.

Those who defend Americas nearly 230-year-old system of electoral votes, and who want to preserve the state-by-state basis of presidential campaigns, need to realize that the historic arrangement is in danger. Without some modifications, the electoral system may not survive another runner-up presidency.

Skeptics will ask whether another second-place president will really be elected soon. The answer, regrettably, is yes. When the country is about evenly divided between its two main political parties, as it is now, the electoral system resembles a risky game of dice. Of the 10 elections in American history when one presidential candidate has come within 3% of the popular vote of another (and this includes the 2000 and 2004 elections), the second-place candidate has won the most electoral votesand the presidencythree times. In short, when an election is close, the chance of a runner-up candidate becoming president is approximately 30% .

Assuming that when the parties are equally balanced only half of the presidential elections will be this close, there is still about a 15% (half of 30%) chance during each election that the runner-up candidate will win.

Even when one party has been dominant, as was true during most of the 20th century, one-sixth of the elections were still quite close. So during a period of one-party supremacy, the chance of a runner-up candidate winning the presidency is still about 5% (one-sixth of 30%). If we split the difference between a 15% chance (when the parties are evenly divided) and a 5% chance (when one party is dominant), there is about a 10% chance in each presidential election that a runner-up candidate will win.

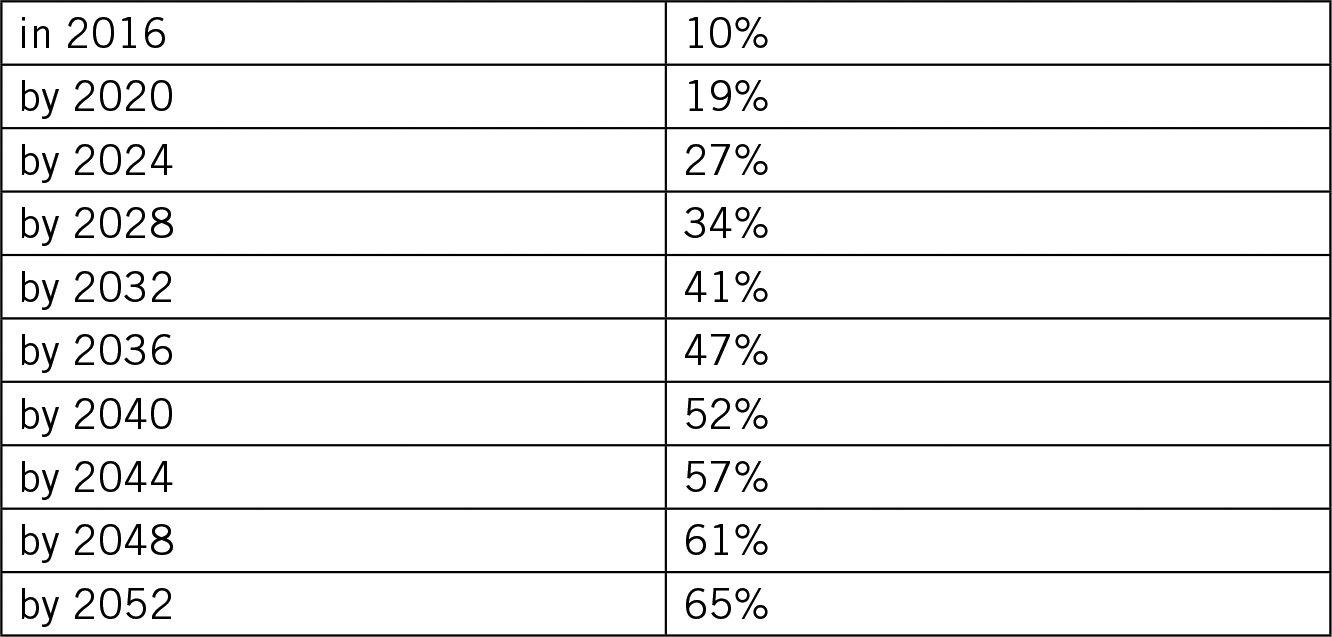

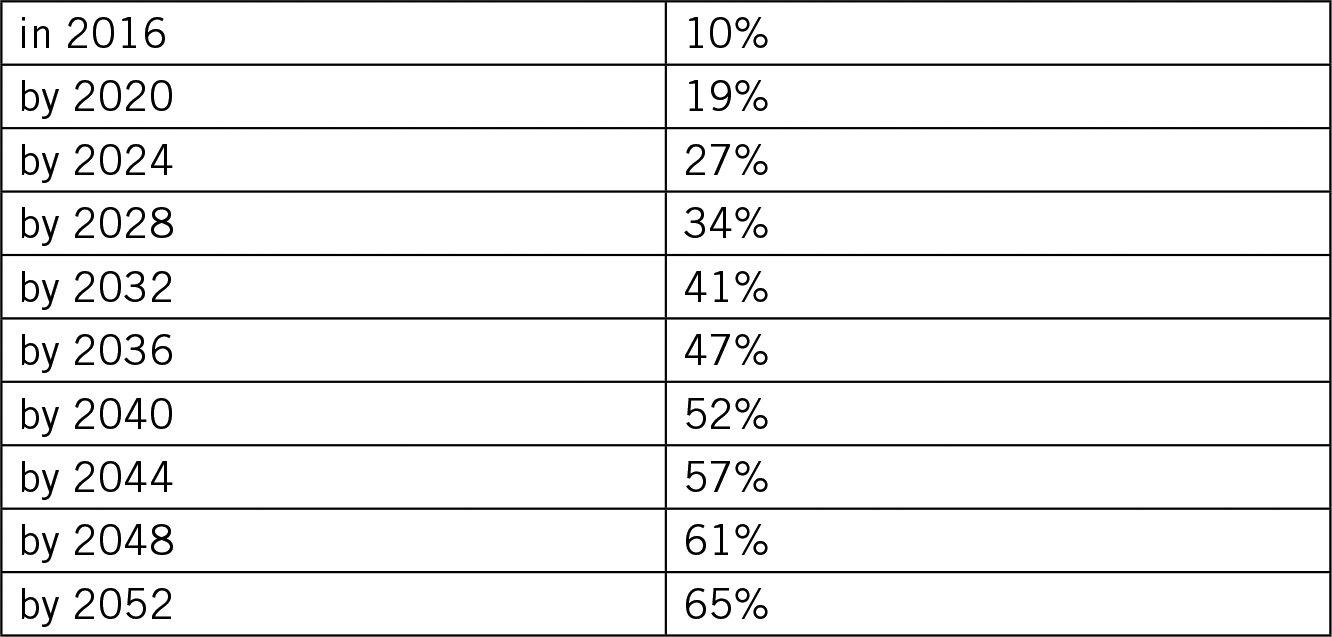

Here are the approximate odds of our country electing another runner-up president:

Cumulative Chances of Electing Another Runner-Up President

It is more likely than not that we will elect another runner-up president in the next 30 or 40 years. Without an adjustment, Americas two-century-old system of electoral votes will threaten both the legitimacy and effectiveness of future presidents.

But the electoral system does not need to be replaced, only repairedpreferably sooner rather than later. Must we really wait until another runner-up candidate moves into the White House, as a majority of Americans watch the news and sigh, Not again?

C HAPTER 1

What Were the Founders Thinking?

The Electoral Systems Oddities, Origins, and Benefits

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.