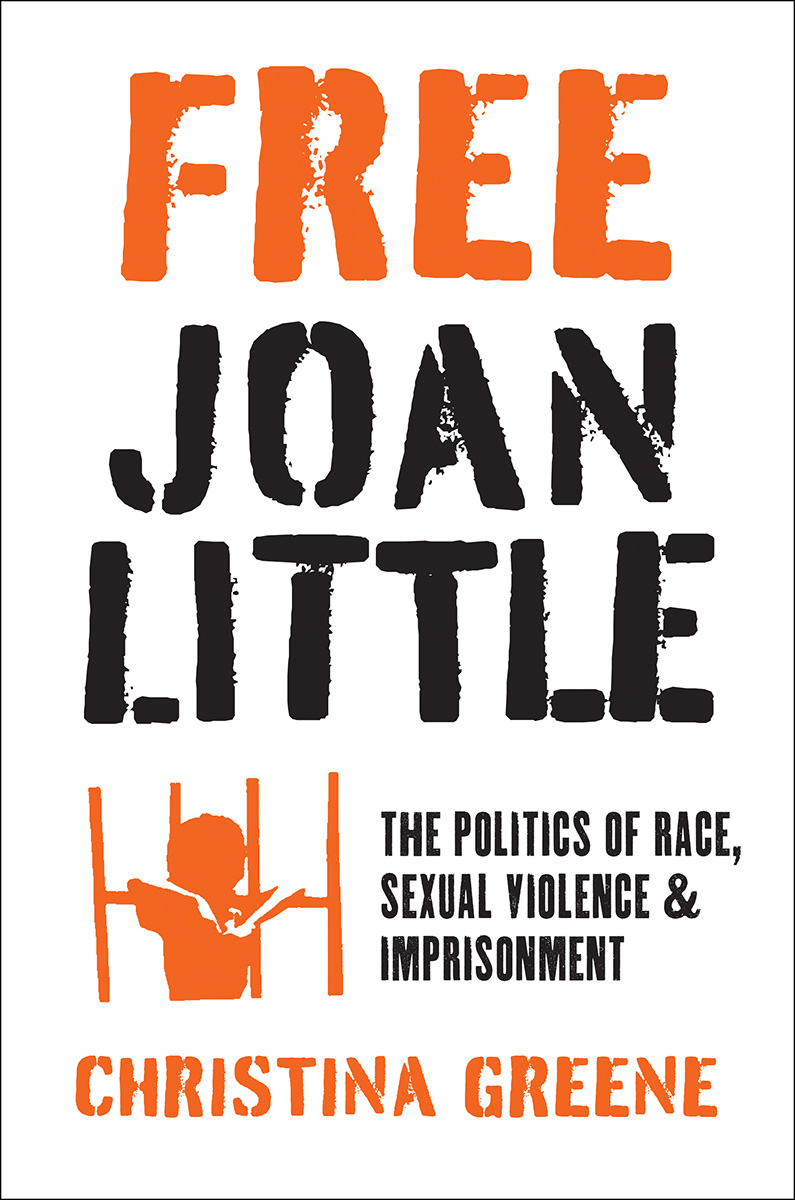

FREE JOAN LITTLE

Justice, Power, and Politics

Coeditors

Heather Ann Thompson

Rhonda Y. Williams

Editorial Advisory Board

Peniel E. Joseph

Daryl Maeda

Barbara Ransby

Vicki L. Ruiz

Marc Stein

The Justice, Power, and Politics series publishes new works in history that explore the myriad struggles for justice, battles for power, and shifts in politics that have shaped the United States over time. Through the lenses of justice, power, and politics, the series seeks to broaden scholarly debates about Americas past as well as to inform public discussions about its future.

More information on the series, including a complete list of books published, is available at http://justicepowerandpolitics.com/.

This book was published with the assistance of the Z. Smith Reynolds Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2022 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Scala, Burnaby Stencil, and News Gothic by codeMantra

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cover silhouette inspired by an image in Triple Jeopardy, the newspaper of the Third World Womens Alliance.

Authors note on language: Throughout this book, I have kept self-naming terms such as negro or colored that were used at the time by African Americans. The N-word, in its entirety, also appears a few times when quoting creative works by Black writers and when referencing or quoting hateful language used by some white people against African Americans in order to demean them. While encountering these words is difficult, I feel its important not to silence the writers or to erase the anti-Black language in the historical record, so I have quoted them verbatim.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Greene, Christina, 1951 author.

Title: Free Joan Little : the politics of race, sexual violence, and imprisonment / Christina Greene.

Other titles: Justice, power, and politics.Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2022] |

Series: Justice, power, and politics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022022448 | ISBN 9781469671307 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469671314 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469671321 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Little, JoanTrials, litigation, etc. | Trials (Murder)North Carolina. | Justifiable homicideNorth Carolina. | Sexual abuse victimsNorth Carolina. | African American womenLegal status, laws, etc. | PrisonersCivil rightsNorth Carolina. | Anti-rape movementUnited States. | African American feministsHistory.

Classification: LCC KF224.L52 G74 2022 | DDC 345.73/02523dc23/eng/20220801

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022022448

For

BONNIE JOHNSON

dear friend and

participant-historian in the

1970s Black Womens Retreat

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figures

Maps

Abbreviations

AAWOAlliance Against Womens OppressionAFFWAction for Forgotten WomenCWJConcerned Women for JusticeDOCDepartment of CorrectionHBCUhistorically Black colleges and universitiesLEAALaw Enforcement Assistance Act / Law Enforcement Assistance AdministrationNABFNational Alliance of Black FeministsNBFONational Black Feminist OrganizationNBWHPNational Black Womens Health ProjectNCCCWNorth Carolina Correctional Center for Women (Womens Prison)NCPLUNorth Carolina Prisoners Labor UnionNOINation of IslamNOWNational Organization for WomenRCCrape crisis centerVAWAViolence Against Women Act

Joan Little, 1975.

Courtesy of the North Carolina State Archives and the Raleigh News and Observer.

FREE JOAN LITTLE

INTRODUCTION They Had No Plans to Capture Her, but to Kill Her

In the early hours of August 27, 1974, prison officials found the jailer, Clarence Alligood, slumped on a bunk in the womans section of the Beaufort County Jail in eastern North Carolina. His lifeless body bore eleven stab wounds, including seven in his chest and one that pierced his heart. Naked from the waist down, except for his brown socks, Alligood clutched his trousers in one hand; an ice pick dangled loosely from the other. A trail of dried semen trickled down his left thigh. His shoes were in the narrow hallway outside the jail cell; a negligee and bra hung on the cell door. The prisoner, Joan Little, was nowhere in sight. She was five feet three inches tall, twenty years old, poor, Black, and in trouble.

Those who believed Joan Little was guilty saw a hardened criminal with the instincts of a black widow spider, a Jezebel who lured the unsuspecting Alligood into her cell with promises of sex. In the moment of his climax, the wanton young woman ruthlessly stabbed and killed the poor, defenseless man. On the other side, feminists of all kinds, Black Power activists, prison abolitionists, Black working-class church ladies, and traditional civil rights leaders saw a victim of sexual violence and racism, a vulnerable Black woman who had valiantly defended herself against one of the age-old and unforgivable crimes of white supremacy. Although they would differ among themselves about whether sexism, racism, or poverty was most salient, her defenders all discerned a young woman, destitute, alone, and terrified at her predicament, who did what any trapped victim would dodefended herself and then fled in a panic.

Darting around hedges, hiding behind buildings, and eluding police in what Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) leader Golden Frinks called the pattern of the old Underground Railroad, Little remained on the lam for less than a week. Officials invoked a Reconstruction-era fugitive law that allowed anyone to shoot and kill the young woman on sight. While in hiding she learned that Alligood was dead and knew her life was in danger, now more than ever. If they had apprehended me,... then my side would never be told, Little recalled. I didnt know about the fugitive law, she said. All I knew was I had to get to somebody.

When Joan walked into Cheniers Durham apartment on September 2, 1974, the Black women rushed to greet her. Hugging and kissing the young fugitive, they were relieved to see her alive. We knew that they were after her with rifles and guns, that they had no plans to capture her, but to kill her, Chenier recalled. That first night I saw Joan Little as myself, as did most of the black women who were there. Joans presence evoked four hundred years of being raped by white men.... Joan Little is me, could be me, and I remember saying at the meeting that I would have done what Joan did, Chenier acknowledged. We all felt that she had done what she had to do. She had defended herself! She had defended her womanhood!

Joan appeared overwhelmed by the affection and support. As the group, about half women, gently pressed her for details, she tried to answer their questions, often uttering only a word or two in response. But when she began to describe the struggle with Alligood over the ice pick, she broke down. Jerry Paul hurried her into to a back room so she could regain her composure, and they left soon afterward. From that gathering, the Free Joan Little campaign was born. The next day, Little, surrounded by her attorneys and supporters, turned herself in to authorities in Raleigh. It took no time for a Beaufort County grand jury to indict her for first-degree murder. If convicted, Joan would face a mandatory death sentence in North Carolinas gas chamber.

Next page