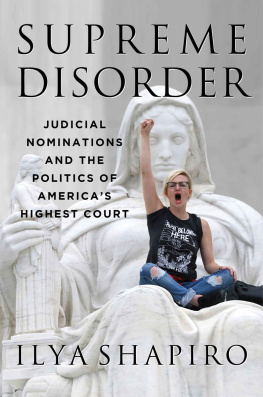

Ilya Shapiro - Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court

Here you can read online Ilya Shapiro - Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Regnery Gateway, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court

- Author:

- Publisher:Regnery Gateway

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ilya Shapiro: author's other books

Who wrote Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Kristin, Jacob, and Charlie

W hen Justice Charles Evans Whittaker retired in March 1962 after just over five years on the Supreme Court, John F. Kennedy had his first opportunity to shape the high court. The youthful president selected a man of his own generation, Byron White. White had met JFK in England while on a Rhodes Scholarshipafter having been runner-up for the Heisman Trophy and spending a year as the highest-paid player in the NFLand the two became fast friends.

White was a vigorous forty-five and serving as the deputy attorney general under Robert F. Kennedy. Kennedy formally nominated him on April 3, 1962. Eight days later, White had his confirmation hearing, a quick ninety minutes including introductions and supporting testimony from various bar association officials (during which the nominee doodled on his notepad). What questioning there was largely concerned the nominees storied football career; Whizzer White was surely the last person to play a professional sport while attending Yale Law School. The judiciary committee unanimously approved him, and later that day so did the Senate as a whole, on a voice vote.

My, how times have changed.

The battle to confirm Brett Kavanaugh showed that the Supreme Court is now part of the same toxic cloud that envelops all of the nations public discourse. Ironically, Kavanaugh was nominated in part because he was thought to be a safe pick, with a long public career that had been vetted numerous times. He was firmly part of the legal establishment, specifically its conservative mainstream, and had displayed a political caginess that made some on the right worry that he would be too much like John Roberts rather than Antonin Scalia or Clarence Thomas. As it turned out, of course, 11th-hour sexual assault allegations transformed what was already a contentious process into a partisan Rorschach test. All told, Kavanaugh faced a smear campaign unlike any seen since Robert Bork.

Senate Democrats had warned President Reagan that nominating Borka judge on the D.C. Circuit after a storied academic and government careerto the Supreme Court would provoke a fight unlike any he had faced, even after Scalia had been confirmed unanimously the year before. And so, on the very day that Reagan nevertheless announced Bork as his pick, Ted Kennedy went to the Senate floor to denounce Robert Borks America as a place in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the government, and the doors of the federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens.

It went downhill from there, as the brusk Bork refused to adopt the now well-worn strategy of talking a lot without saying anything. A few years later, Ruth Bader Ginsburg would refine that tactic into a pincer movement, refusing to comment on specific fact patterns because they might come before the Court, and then also refusing to discuss general constitutional principles because a judge could deal in specifics only.

Confirmation processes werent always like this. The Senate didnt even hold public hearings on Supreme Court nominations until 1916, a tumultuous year that witnessed the first Jewish nominee and the resignation of a justice to run against a sitting president. It wouldnt be until 1938 that a nominee testified at his own hearing. In 1962, the part of Byron Whites hearing where the nominee himself testified lasted less than fifteen minutes.

But while the confirmation process may not have always been the spectacle it is today, nominations to the highest court were often contentious political struggles. For the republics first century, confirmation battles, including withdrawn and postponed nominations, or those upon which the Senate failed to actMerrick Garland was by no means unprecedentedwere a fairly regular occurrence.

George Washington himself had a chief justice nominee rejected by the Senate: John Rutledge, who had lost Federalist support for his opposition to the Jay Treaty. James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, also had a nominee rejected. And John Quincy Adams, who himself had declined a nomination from Madison, had a nominee postponed indefinitely during the lame duck period after Andrew Jackson had stopped his bid for reelection.

Jackson then had a nominee thwarted, but a change in Senate composition allowed Roger Taney to become chief justice a year laterand eventually author Dred Scott. John Tyler, who assumed the presidency in 1841 after the one-month presidency of William Henry Harrison, never lived down his nickname of His Accidency. Congressional Whigs disputed his legitimacy and their policy disagreements extended to judicial nominations: the Senate rejected or declined to act on four Tyler nominees (three of them twice) before finally confirming one.

Indeed, most 19th-century presidents had trouble filling seats on the high court. Millard Fillmore was prevented from filling a vacancy that arose during his tenure, as was James Buchanan. Congressional elimination of Supreme Court seats stopped Andrew Johnson from replacing the two justices who died during his presidency. It took Ulysses Grant seven tries to fill three seats. Grover Cleveland ran into senatorial traditions regarding seats reserved for certain stateswhich he overcame only by nominating a sitting senator.

In the 20th century, Presidents Harding, Hoover, Eisenhower, Johnson, Nixon, and Reagan all had failed nominationsalthough Harding and Ike got their picks confirmed after resubmitting their names. FDR never had anyone rejectedalthough his court-packing plan was rejected both in Congress and at the polls. And LBJs proposed elevation of Justice Abe Fortas led to the only successful filibuster of a Supreme Court nominee, a bipartisan one over ethical concerns, which wasnt even a true filibuster because Fortas never had a majority of pledged votes. Douglas Ginsburg withdrew before President Reagan could send his name to the Senate for having smoked marijuana with his law students.

Then of course theres Merrick Garland, the first nomination the Senate allowed to expire since 1881but then the last time a Senate controlled by the party opposite to the president confirmed a nominee to a vacancy arising in a presidential election year was 1888. As we now know, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnells gamble worked: not only did it not hurt vulnerable senators running for reelection, but the vacancy held Republicans together and provided the margin for Donald Trump in key states. Trump rewarded his electoral coalition with the nomination of Neil Gorsuch, who was confirmed only after the Senate decided, on a party-line vote, to exercise the nuclear option and remove filibusters.

Opportunities for obstruction have continuedpushed down to blue slips, cloture votes, and other arcane parliamentary procedureseven as control of the Senate remains by far the most important aspect of the whole endeavor. The elimination of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees was the natural culmination of a tit-for-tat escalation by both parties.

More significantly, by filibustering Gorsuch, Democrats destroyed their leverage over more consequential vacancies. Moderate Republican senators wouldnt have gone for a nuclear option to seat Kavanaugh in place of Anthony Kennedy, but they didnt face that dilemma. And they wont face it if President Trump gets the chance to replace Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg or Stephen Breyer, which would be an even bigger shift.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court»

Look at similar books to Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of Americas Highest Court and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.