Contents

Guide

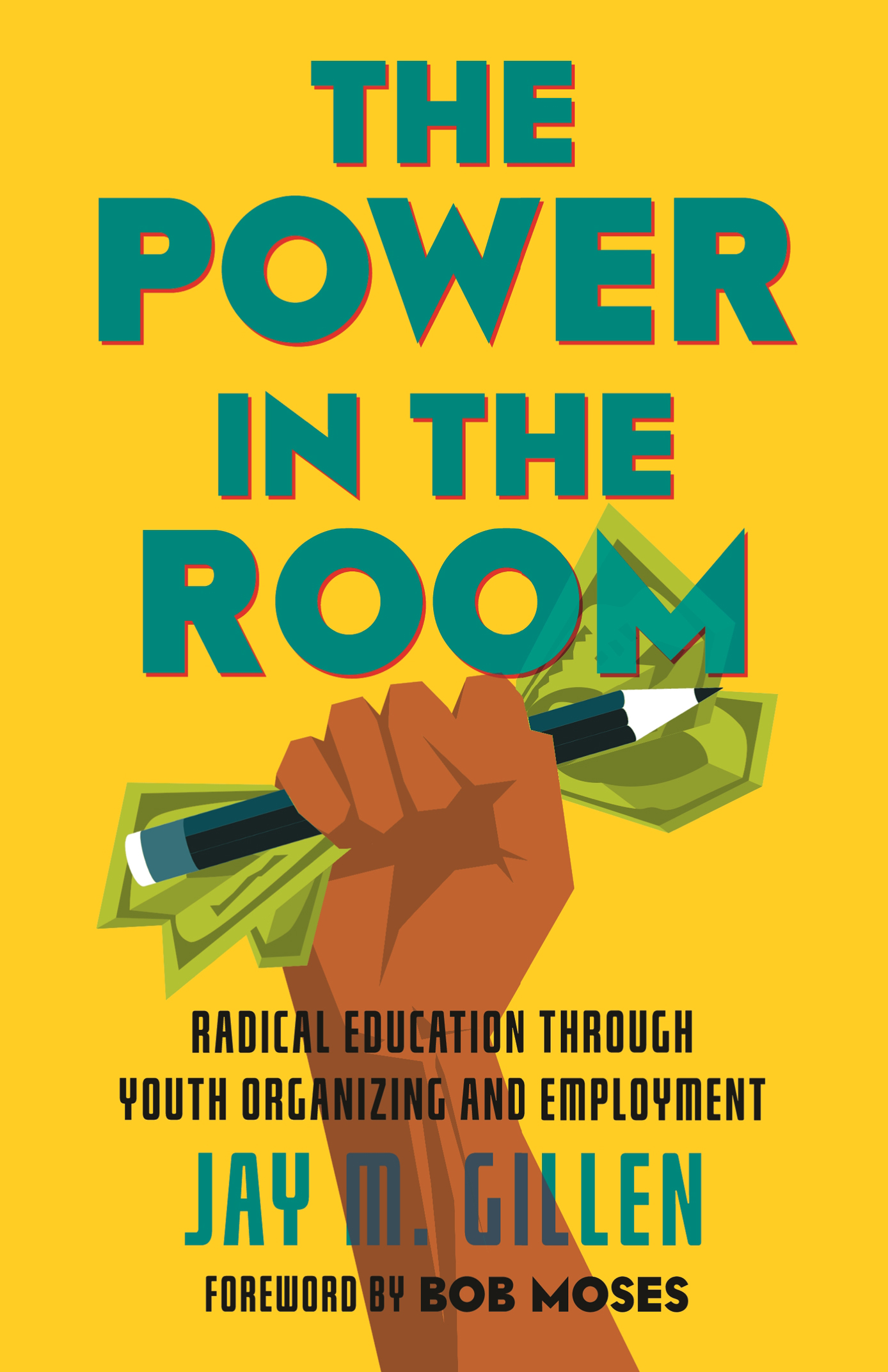

For Thomas Nikundiwe

Young people are the power in the room.

Omo Moses

FOREWORD

Meet Alex, CMG, Deonte, Leon, David, TS, Daysha, Jamie, Katherine Engleman, Alanis Brown, Mira, Salima, Crystal, Bryan, Sherrod, Ms. T, and LS.

Meet them in this book by Jay Gillen, a writer who, in the language of Toni Morrison, is unsettling, calling into question, taking another deeper look... whose writing is trouble for the warmonger, the torturer, the corporate thief, the political hack, the corrupt justice system, and for a comatose public.

Importantly, he wrote this book in his own language: It is how I talk to myself about how the young people talk to themselvesthese young people of the Baltimore Algebra Project (BAP) with whom he has lived and learned how they talk to themselves for the past three decades.

Reflect that Jay and BAP youth, again in Morrisons language, come together to respond to their perception of chaos by enacting Morrisons atypical third response to chaos: Stillness: not passivity, dumbfoundedness, or paralytic fear, but art. The art of creating a life within an earned insurgency:

BAP youth collectively take on the work of making better arrangements for their lives than other people have done so far.

BAP youth construct, with their lives, meaning in the face of chaos.

Morrison speaks of certain kinds of trauma visited on people [that] are so deep, so cruel, that unlike money, unlike vengeance, even unlike justice or rights, or the goodwill of others, only writers can translate and turn sorrow into meaning. Such is the gift of Jays book, or, as Morrison says, the necessity.

BOB MOSES

Toni Morrison, Peril, The Source of Self-Regard (New York: Penguin Random House, 2019), vii-ix.

INTRODUCTION

Organizing, Economics, and the African American Educational Tradition

I descend from a line of Jewish teachers who worked in Eastern Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Near Suwalki, now in Poland, they ran their own secular Jewish schools as modernistsboth men and womentranslating the new genre of science fiction, for example, from French into a reinvented Hebrew. Some of them were socialists, fighting for freedom from ethnic and economic oppression. Many, including my gentle grandfather, fled from intolerable circumstances. All were victims of Russian, Polish, and Christian persecution, and the Nazi Holocaust left not a single Jew alive in the places where my ancestors once lived.

I have been a teacher for more than thirty years in Baltimore, where most of our public schools are desegregated in name only. I have come to follow and collaborate with a line of African-ancestored teachers who embody a tradition that sustains hope and joy in extraordinarily difficult circumstances. These teachers, both in and out of schools, draw on centuries of educational practices within Black communities that center around an idea of dignity, an essential worthiness, from which freedom can be grown and nurtured despite the surrounding hate. Their practices feel familiar to me in the quality of their ethics and the connection they assert between the work of the mind and political justice. I imagine a common ethical source for all cultures emerging from our shared human origins in Africa.

Many of the elements of an African American philosophy of education are spelled out and documented by scholar-activists such as Theresa Perry, Vincent Harding, Vanessa Siddle Walker, Heather Williams, Russell Rickford, Charles Payne, Carol Strickland, and others:

Children must develop identities as people who do intellectual and knowledge work but without creating a false dichotomy between the work of the mind and the work of the hands and body. Intellectual and cultural celebration must be integrated into each childs personality as an ordinary part of their daily activities, and that integrated personality must be encouraged to find expression and usefulness through thinking, communicating, moving, and making.

Both peer and intergenerational group contexts are important for developing identity. African American children and young people can and do create group identities around their intellectual and cultural brilliance. This must be affirmed by everyone around them.

The historically dynamic achievement of African American educational institutions should be taught explicitly, so that young people come to see themselves as part of a sustained effort to imagine and help realize a more just world.

The teachers I learn from in this tradition see each childs life in their care as both unique and representative: unique in the sense that each individual human being deserves to learn and to thrive; and representative in the sense that no one can escape the judgments of the worldthe tests, the confrontations, the sufferingand these teachers therefore long to read in each childs life, and in the lives of all the communitys children, a story of overcoming, a story of survival and even of victory.

Thousands of teachers, artists, artisans, musicians, preachers, intellectuals, farmers, cooks, and poets have thought of themselves as raising Black children into adulthood so that those children could lift every voice and sing, as the anthem urges. Sometimes they have started schools or churches, sometimes they have joined already-existing institutions to create the environment where children could both thrive in the present and also learn to cope with the shared human burden, especially heavy for African children in America, of carrying the past successfully into the future.

As with all human endeavors, this work of education is never smooth. The violence of America tries to obliterate Black cultural abundance. The cruelty of poverty or of patriarchy still blocks pathways to intellectual development. Illness constricts effort, but also ego, envy, fear, or simply misunderstandings and failures of generosity and empathy. Prominent, too, are the obstacles generated by personal success. Class divisions within oppressed communities are exacerbated and exploited by both the economics and the symbolism of White capitalist supremacy. These divisions often poison relations even between members of the same family, and class markers can end up taking on a life of their own.

But obstacles are not the end of the story. The ideas developed in this book try to advance strategies that have emerged and continue to exist right within the hollows and openings of American power. In particular, I try to reconnect three aspects of freedom work that have always been understood to go together but whose relation to each other has become confused and difficult to see. We tend to think of education as one thing, and we think of economics as something separate from education. In popular understanding, the connection between the two is that you need an education to get a job: the one comes first; the other comes after. But things are not so simple. And the relation between education and a third aspect, political action or organizing, is even more complex. In the African American liberatory tradition, education, economic strategies, and organizing for freedom must be developed all at once or not at all. They are in fact one topic, not three.

I teach nowadays in a womens jail in Marylanda jail for young women, as young as eleven, as old as nineteen. Although African Americans make up only 30 percent of the state population, they are 77 percent of the jailed youth.