Published in 2015 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2015 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Expert Reviewer: Lindsay A. Lewis, Esq.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brezina, Corona, author.

Alcohol and drug offenses : your legal rights/Corona Brezina.

pages cm.(Know your rights)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4777-8032-9 (library bound) ISBN 978-1-4777-8033-6 (pbk.) ISBN 978-1-4777-8034-3 (6-pack)

1. Narcotic lawsJuvenile literature. 2. Drugs of abuseLaw and legislationCriminal provisionsJuvenile literature. I. Title. K3641.B74 2015 345.730277dc23

2014021740

Manufactured in the United States of America

CONTENTS

D eMarcus Sanders was attending college and working at a janitorial job when he was arrested on a first-time charge for possession of marijuana in Waterloo, Iowa. He was sentenced to thirty days in jail and a fine, but Sanders was unable to get his life back on track after being freed. He lost his job and college credits. His driver's license was suspended, and the state refused to reinstate it since he was unable to pay thousands of dollars in fines. Waterloo is a small city without much public transportation. Sanders had trouble finding a job that didn't require driving to work. Without steady work, he couldn't earn money to pay the fines.

Sanders's case serves as one example of the consequences of a drug conviction in the United States. If Sanders were arrested today in California on a first-time possession charge, he would probably receive only the equivalent of a ticket, requiring that he pay a small fine. If he lived in Colorado, possessing marijuana would be legal. In some other states, however, he might face an even harsher sentence than Iowa's penalties. As in this case, even a first-time possession can have consequences. A college student could lose financial aid or become ineligible for a job in an FDIC-regulated organization such as a bank or in law enforcement. Whatever the charge, in whichever state it happens, it is best to talk to a lawyer to get the best possible outcome.

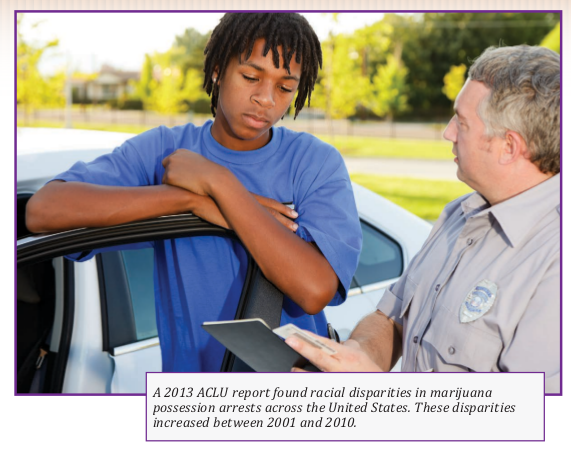

Sanders's case demonstrates another trend in the enforcement of drug laws. According to analysis by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), an African American person is more than three times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession as a white person, even though both groups use marijuana at about the same rates. In the ACLU report, Sanders describes how he felt targeted because of his race. On a later occasion, police detained and searched him after he crossed a street in downtown Waterloo, even though he had not violated any laws. They found marijuana in his possession and issued a citation. Sanders fought the case, claiming that his constitutional rights had been violated. A judge agreed, ruling in his favor.

Anyone involved in a court case will benefit from knowing his or her legal rights and understanding how to navigate the system. The justice and penal system can be bewilderingly complex. A young person suddenly thrown into this system often lacks the basic legal information that could help achieve the best possible outcome. Drug-related crimes often involve serious charges punishable by severe penalties. Even petty charges can have lifelong repercussions if not handled correctly. It is important to take any and all cases seriously.

Everybody can benefit from having legal savvy, regardless of personal involvement in the system. Understanding the consequences up front, and knowing what kind of action to take in the event of a summons or arrest, can lessen negative consequences. If you possess some fundamental knowledge about federal, state, and local laws and the typical penalties for various crimes, you can share this information with family and friends. More importantly, you can learn how to avoid getting into trouble with the law.

CHAPTER 1

ALCOHOL

A lcoholism is a public health problem in the United States. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism lists alcohol-related causes as the third leading preventable cause of death in the United States. It costs nearly eighty-five thousand people their lives every year. Nearly a quarter of all Americans reported in a 2012 survey that they had engaged in binge drinking in the previous month, and 7.1 percent qualified as heavy drinkers. However, fewer than one out of five people with alcohol abuse disorders sought treatment. Alcohol problems cost the nation about $224 billion annually in lost productivity, health care and property damage costs.

Alcohol use is also an issue for teenagers. According to the annual Monitoring the Future survey, which tracks substance use among young adults, more teenagers abuse alcohol than any other substance. About seven out of ten teens have used alcohol before finishing high school, and three out of ten eighth-graders have used alcohol. Over half of all high school seniors and one out of eight eighth-graders have been drunk. However, overall rates of alcohol use by teens have been declining since 2002.

THE LEGAL DRINKING AGE

Most people know that twenty-one is the legal drinking age in the United States, and that it's illegal for anyone younger to consume alcohol. However, there are varying laws and policies about alcohol possession that are subject to federal, state, and local control. Adults younger than twenty-one are generally prohibited from possessing alcohol, but certain limited exceptions are regulated by state laws.

Until the 1980s, there was no national minimum drinking age. During the 1960s and 1970s, many states reduced the legal drinking age to eighteen, nineteen, or twenty years. Concern grew during the early 1980s about the higher rate of drunken driving fatalities in states with lower minimum drinking ages. The National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 was passed to address the issue. It set the national minimum drinking age at twenty-one years.

Laws concerning alcohol, however, fall under both federal and state authority. The federal government regulates importation and taxation of alcohol. States set their own laws for sales, distribution, possession, and importation of alcohol across state lines. Under the U.S. Constitution, the federal government does not have the authority to impose a condition, such as a minimum drinking age that would interfere with the states' rights to determine their own laws.

The National Minimum Drinking Age Act got around this limitation by requiring states to reset their laws to a minimum drinking age of twenty-one. (In Canada, provinces and territories set their own liquor laws, and the legal drinking age is set at either eighteen or nineteen across the country.) States had the option of refusing, but the decision would be costly; any state that did not raise the minimum drinking age to twenty-one would have its federal funding for highways cut by 10 percent. By 1988, every state had complied with the requirements of the act.