Contents

Page List

Guide

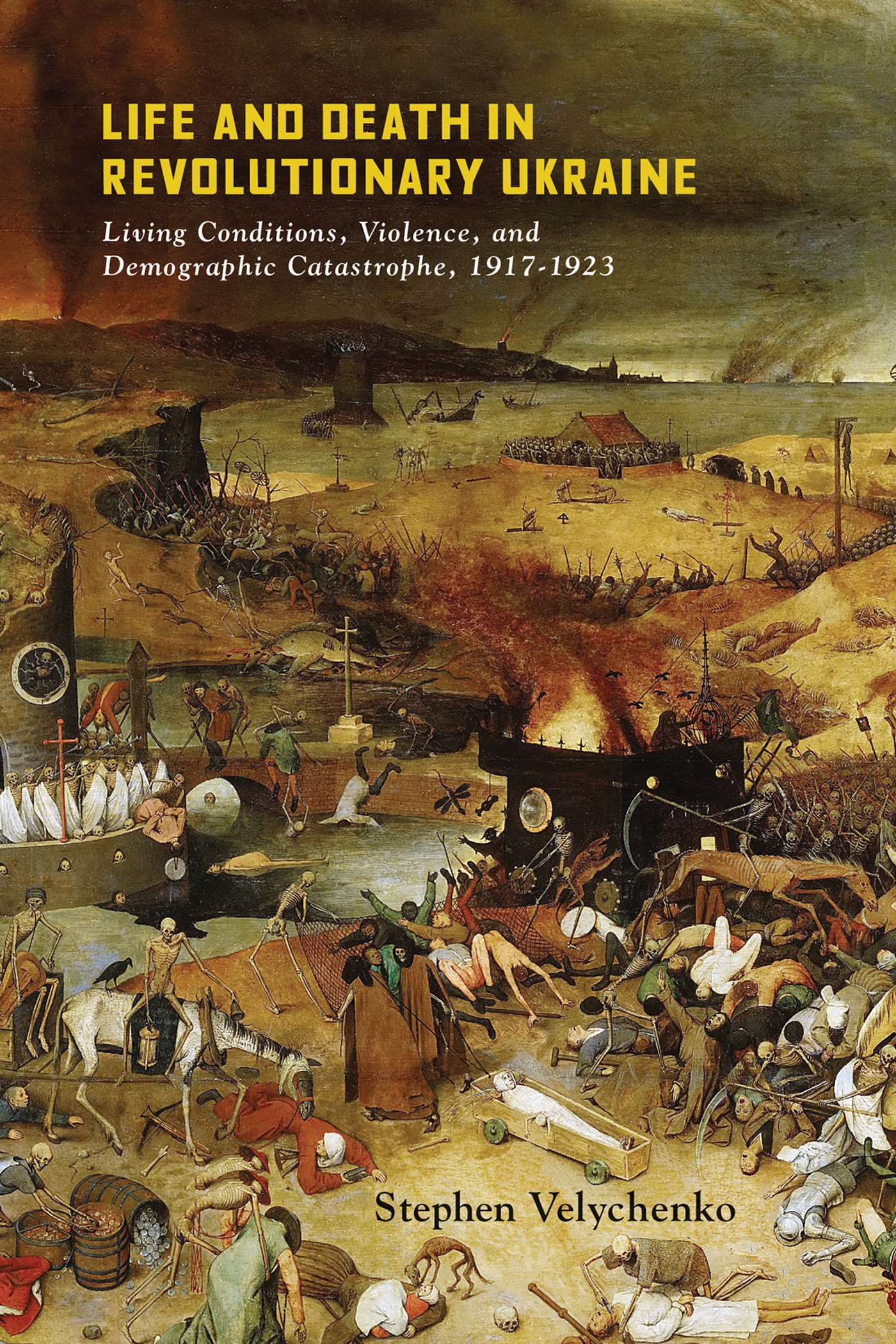

LIFE AND DEATH IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE

LIFE AND DEATH IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE

Living Conditions, Violence, and Demographic Catastrophe, 19171923

STEPHEN VELYCHENKO

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Chicago

McGill-Queens University Press 2021

ISBN 978-0-2280-0897-2 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-2280-1029-6 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-0-2280-1030-2 (ePUB)

Legal deposit fourth quarter 2021

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free (100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free.

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Life and death in revolutionary Ukraine : living conditions, violence, and demographic catastrophe, 19171923 / Stephen Velychenko.

Names: Velychenko, Stephen, author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210271582 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210271663 | ISBN 9780228008972 (cloth) | ISBN 9780228010296 (ePDF) | ISBN 9780228010302 (ePUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Violence Ukraine History 20th century. | LCSH: Ukraine History Revolution, 19171921 Atrocities. | LCSH: Ukraine History Revolution, 19171921 Health aspects. | LCSH: Ukraine Social conditions 20th century. | LCSH: Ukraine Politics and government 1917-1945.

Classification: LCC DK265.8.U4 V45 2021 | DDC 947.708/41 dc23

This book was designed and typeset by Peggy & Co. Design in 10.5/13 Sabon.

Contents

LIFE AND DEATH IN REVOLUTIONARY UKRAINE

Introduction

While the contest between man and man may be more spectacular and may involve greater destruction in mass, the assault by the microbes is far more insidious, more elusive, and on the whole far more deadly. Indeed war is in a sense simply an incident which man foolishly permits to enter into that greater struggle with germ life

David Davis, Professor of Bacteriology, University of Illinois, 1917

Between the outbreak of the Balkan Wars in 1912 and the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, Europeans from Finland to Greece, Ireland to Armenia, lived through an apocalyptic decade of war, pestilence, famine, and death. Ukraine was one of the countries where war, revolution, and societal collapse produced demographic catastrophe. Part of what Churchill called the wars of the pygmies, and the unknown war in eastern Europe, events in Ukraine were as messy and deadly as those in the Balkans, or on the front lines in the war of the giants in France.

In the last decade, historians shifted from a previous focus on high politics and battles on the Western Front, and now relate what the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse did behind the fronts in eastern and south-eastern Europe: the physical destruction, civilian deaths, maiming, rape, deportations, disease, impoverishment, and depravation. To that total, Ukraines losses between 1917 and 1923 should not be excluded.

The Political Events

Eastern Ukraine belonged to the tsarist empire in 1914. With the abdication of the tsar, Ukrainian socialist leaders created the Central Rada in March 1917. That November, they proclaimed the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) and claimed authority over the Ukrainian provinces of the Russian Empire. In April 1918, with the backing of German generals, Ukraines financiers, industrialists, and landowners, the Ukrainian-born tsarist General Pavlo Skoropadsky overthrew the Central Rada. He established a neo-monarchist regime called the Ukrainian State (Ukrainska Derzhava) with himself, as hetman, at its head. Skoropadsky abdicated one month after Germanys surrender in November 1918. In his place, Volodymyr Vynnychenko and Symon Petliura re-established the UNR and declared themselves the heads of its temporary government the Directory.

The Ukrainian State and the Central Rada held a core territory of five tsarist provinces for at least six months each. The borders of the Directory-ruled UNR fluctuated with the fortunes of war. Its core was an area of land measuring roughly 200 square kilometres, including most of Podillia province and parts of Volyn and Kyiv provinces. During 1919, UNR territory was about equal in size and population to Bolshevik Ukraine. It presided in these regions for two periods of no longer than five months each: between December 1918 and April 1919, and then from August to November 1919. The total population in this area varied between three and ten million. In the south-east, the border moved back and forth in the wake of war with the Whites and Nestor Makhnos army. The only territory the Directory controlled with only a few weeks interruption was the area around the city of Kamianets-Podilskyi. The Directory collapsed in December 1919. It established a government-in-exile in Poland and had to allow Polish troops to occupy territory as far east as the Zbruch River.

Representing between ninety and ninety-five of Ukraines three hundred Soviets, Ukraines Bolsheviks seized power in Kharkiv on 12 (25) December 1917. They set up a government with the help of approximately 4,500 troops and Red Guards, of whom approximately 2,100 had arrived from Moscow the previous week. Of the twelve members of the newly formed Peoples Secretariat, four were Ukrainians and four were Ukrainian-born Germans. Until August that year, Bolshevik Ukraines core territory was a region of 300 square kilometres around the north-eastern town of Chernihiv. In the west, the border shifted following the war with the Directory. Bolsheviks ruled most of what had been tsarist-Ukraine from January 1920. Until 1923, their control was challenged by guerilla forces led by Makhno and warlords (otamany).

Western Ukraine (eastern Galicia) had belonged to the Austro-Hungarian empire. With its collapse, the Polish Liquidation Commission in Krakow claimed authority over the entire province of Galicia as part of the new Polish state. In its last official act, however, the Habsburg monarchy, on 31 October 1918, denied the Liquidation Commission any authority over eastern Galicia and instructed its governor to appoint Ukrainians to all government posts there. The instruction was telegraphed to Krakow that evening, but the Liquidation Commission did not forward it to Lviv (Lwow, Lemberg). By 22 November, Poles controlled the city thanks to reinforcements from Poland. These could arrive because Ukrainians had failed to hold Przemysl (Peremyshl), where the bridge over the San River linked Krakow and Lviv. Ukrainians negotiated with Polish leaders rather than arresting them and failed to blow up the bridge when they could have.

Western Ukrainian leaders claimed sovereignty over fifty-two eastern Galician districts (povit, powiat, bezirk), with approximately six million people, and an area slightly bigger than Ireland. With the loss of Lviv, Przemysl, and their environs, the ZUNR controlled forty districts, which in 1910 had just under four million people and was about as big as the 1922 Irish Republic. Fifteen per cent of this areas urban population was Ukrainian speaking. Poland conquered the ZUNR in July 1919 after a seven-month war. Before western Ukraine was incorporated into Poland as Malopolska Wschodnia, it was briefly ruled by the Bolsheviks as the Galician Soviet Socialist Republic.