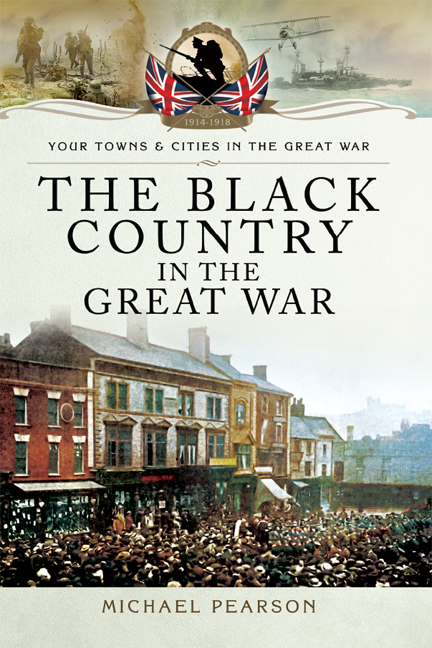

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Michael Pearson, 2014

ISBN 978 1 78337 608 7

eISBN 9781473840942

The right of Michael Pearson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in Times New Roman by Chic Graphics

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery,

Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways,

Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press,

Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

Every project I undertake is first of all discussed with my greatest supporter, copy typist and sufferer, my wife Lin. She has always been supportive of my work, even though she may hide thoughts such as not again or What this time? I also want to thank Pen and Sword for allowing me to combine two passions of mine: the Black Country and military history. The latter stems from schooldays with my history teacher, Barry Miles, a Welshman who looked a little like Ernie Wise, and the former is due to my own research into my ancestors, Woodside miners born and bred. I quickly became diverted into more general Black Country local history research and thanks to Stan Hill, I joined the band of enthusiasts on the committee of the Black Country Society.

I also want to thank the staff at the Black Country Living Museum, especially Jo Moody and Helen Taylor, for their assistance and cooperation. We are all looking into the Great War and have been able to feed from each other with regard to research material. My gratitude goes to Dave Kerr from the Birmingham and Midland Society for Genealogy and Heraldry for his sharing of family research; and finally, to Doctor Paul Collins for allowing me to use images from his collection.

Images

Images in this book have been obtained from a number of sources. Those obtained directly have been duly acknowledged but some have been acquired on the open market and, despite attempts at tracing their origin, many remain anonymous. These images are normally credited to the collection of the author. Ownership of a print of a photograph or a copy of a postcard does not confer copyright upon the owner. In such instances copyright rests with the original photographer, the company for whom the image was taken, or the person, organization or company to whom copyright has been assigned. Again, such photographs are usually credited to the collection contributor. If, through no fault of my own, photographs or images have been used without due credit or acknowledgement, my apologies are offered. If anyone believes this to be the case, please let me know and the necessary credit will be added at the earliest opportunity.

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

The Black Country border

When researching and writing, as my self-imposed border for material I use the four boroughs that form the Black Country part of the wider West Midlands: Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton. Occasionally I stray outside these boundaries, especially if the information is of sufficient interest and relevance to the subject. This may not be everyones idea or view of the Black Country but it does make research more straightforward.

The Black Country is that area of what is now the West Midlands that lies to the west of Birmingham. At the time of the First World War it was divided between Staffordshire and Worcestershire. Major towns include Walsall, Wolverhampton, West Bromwich and Dudley, the latter being the unofficial (but disputed) capital of the region.

The Black Country has no specific geographic boundary; its traditional area is that land that sits above the 30-foot-thick South Staffordshire coal seam. This loosely-defined boundary has led to many debates and disputes about who is and who isnt in the Black Country, which means there are as many interpretations as there are people who have an opinion on the subject. I choose to use the four boundaries containing sections of that earlier definition: Dudley, Wolverhampton, Walsall and Sandwell. This may be something of a cop-out but it does make my research much easier as I can use material from the four archives, one for each metropolitan borough.

Background to the Black Country

At the turn of the twentieth century the Black Country was a major industrial area and had been a large contributor to the development of the British Empire throughout the reign of Queen Victoria. Industrialization was at a peak and this would be a crucial factor during the war in terms of the manufacture of munitions and weapons, including the introduction of the tank to combat. As the war progressed, the Black Country looked like one huge munitions works, producing much of the countrys ammunition as well as tanks and other essential equipment. This war changed the shape of the Black Country forever; not only physically because of the building work needed to service the munitions industry but also socially.

The greatest social changes involved women: as more and more men went into the armed services, demand for essential workers created opportunities and threats for women. Prior to the war, women had largely been stay-at-home housewives and mothers to large families with only a small proportion of them going out to work. During the war women became clerks, factory workers, tram drivers, leather workers and carried out a whole range of other jobs. Only four years before the war began, women chainmakers from Cradley Heath fought a bitter strike to break themselves out of the slavery imposed on them by unscrupulous employers who paid them as little as 1d an hour. This strike would lead to the first Nationally-agreed minimum wage and began the end of the so-called sweated trades.

By the end of the war women over the age of 30 were granted the right to vote and were also allowed to stand for Parliament. Women became more than housewives and mothers: they worked in factories, on trams, in offices; in fact in any workplace where they were needed to replace the men who had gone to war. Some men in the Black Country were exempted from being called up. Mining and heavy industry was essential war work and the workforce had to be maintained and protected. However, this would change in the latter years of the war, as needs dictated.

Weapons and munitions have become much more sophisticated over the centuries and in the early twentieth century their production took a great proportion of the output of our industries. It was these joint demands that inevitably led to great change in the Black Country during and after more than four years of war. From this large population centre many men volunteered or were called up to fight; that process starting right from the commencement of conflict. This denuded many employers of valuable workers but their jobs still had to be done and this led to the employment of women in traditionally male occupations.