Contents

Guide

Copyright 2018 by the Los Angeles Times

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

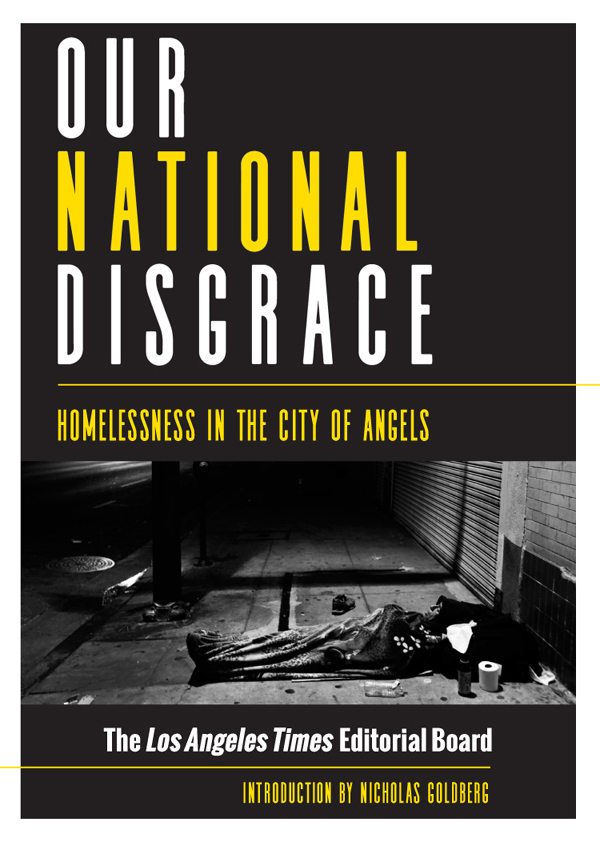

Book and cover design by Ashley Ingram

Cover photo and all interior photos by Francine Orr/ Los Angeles Times

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

With the gap between rich and poor continuing to widen in the United States, with housing prices rising at double the rate of wages, and with nearly half the country convinced that government aid to the needy does more harm than good, it should perhaps come as no surprise that homelessness remains at crisis levels in cities around the nation.

According to the latest figures from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, there are now more than 550,000 people in the country who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate place to sleep on any given night.

To highlight the continuing reality of homelessness and destitution in one of the worlds richest countries, a special UN-appointed monitor on extreme poverty recently undertook an unusual fact-finding mission around the United States. At the end of his two-week mission through Alabama, California, West Virginia, and Washington DC, among other places, he criticized the United States for rejecting access to housing and sanitation as essential human rights and spoke scathingly of Americas bid to become the most unequal society in the world.

The good news is that homelessness has been steadily declining around the country since 2006. But California has defied that trend. It is herewhere 25 percent of all the nations homeless people livethat the problem is concentrated, and it is in Los Angeles where the problem is most severe and most visible. Here, homelessness is not hidden in emergency shelters as it is in New York. Tent cities and sprawling squatter camps have spread from downtown LAs dismal and notorious Skid Row to the farthest reaches of Los Angeles County. Destitution is visible on a daily basismen, women, and children sleeping in alleyways, begging in shopping centers, keeping dry in tunnels, underpasses, and train stations. The extent and severity of Los Angeless homelessness problem has set up an inevitable tension between the needs of the city and the rights of the homeless, and, as in other cities, has provoked an unavoidable fight over what are the best solutions and who should make the sacrifices to achieve them.

Of course, neither the fact of homelessness nor the debate over how to address it is new to this city. Nor is the temptation to blame the victims themselves.

As early as 1882, in its second year of publication, the Los Angeles Times wrote that the city was infested with vagrantsan insolent, impudent and vicious lot. The editorial continued: Dont feed the worthless chaps. It only encourages them in their idleness and viciousness. There is no cause for begging. They could all get work at good wages if they would accept it. Whenever a healthy vag solicits a meal or money you do not do your duty if you do not inform the police and have the beggar arrested.

A year later, the city passed an ordinance promi-sing fines and punishments to anyone who didnt seek employment, who solicited alms, who roamed from place to place, was idle or dissolute or lewd or lived in a house of ill fame, or was a common prostitute or drunkard or vagrant.

Homelessness in Los Angeles spiked during the Great Depression. (Thats when The Times praised the chief of the Los Angeles Police Department for turning back tramps and hobos at the states borders regardless of opinion as to the strict legality of [his] measures.) And homelessness became a national issue again after the deinstitutionalization of mental asylums. The Los Angeles Times won a Pulitzer Prize in 2002 for a series of editorials on the civil liberties of mentally ill people living on the streets.

Today, with an acute housing shortage in California and increasing gentrification leading to displacement in Los Angeles, the numbers are climbing again. Homelessness has risen every year in LA since 2013.

It was against this dismal backdrop that the Los Angeles Times editorial board set out to address the homelessness catastrophe, raise awareness, clear up misconceptions, exhort politicians to actionand then try to sort out the paths forward. Our six-part series began at the end of February 2018.

The editorials raised a number of fundamental questions about homelessness: Is it an indicator of a fatal flaw in our market economies? Is it an inevitable by-product of our selfish insistence on a single-family-home lifestyle? Is it the result of the decision by liberal civil libertariansor, conversely, Ronald Reaganto close the nations mental institutions? Is it the Democrats fault? The Republicans? Is it driven by mental illness and drug addiction or by poverty?

We took on a variety of complicated policy issues that face not just Los Angeles but cities around the country, including the inevitable battle over the siting of homeless housing in residential neighborhoods, the need to balance the rights of the homeless with the rights of other city residents, and the continuing efforts to bring services to the mentally ill homeless. A staff photographer and a videographer illustrated the series with shocking images of people living on the streets all across the cityimages that would be even more shocking if they werent so increasingly familiar.

For decades, politicians have promised solutions to the problem of homelessness, but have fallen short. In Los Angeles, as elsewhere, this has been due to fractious, competitive local politics and fear on the part of elected officials of a powerful voter backlash against the kinds of solutions that are required to address the problem.

But in fact, Los Angeles voters have made it clear at the ballot box in recent years that they are ready for strong action to address the problemand that theyre willing to pay billions of dollars in new taxes to ensure that housing gets built for the homeless and that social services are provided for those who need them. We hope that this editorial series will help persuade those with the power to make change that waiting for the problem to go awayor, more likely, to get worseis no solution at all.

I

LOS ANGELESS HOMELESSNESS

CRISIS IS A NATIONAL DISGRACE

A man sits quietly on a sidewalk in the Skid Row neighborhood of Los Angeles.

THERE ARE FEW SIGHTS IN THE WORLD LIKE NIGHTTIME in Skid Row, the teeming Dickensian dystopia in downtown Los Angeles where homeless and destitute people have been concentrated for more than a century.

Here, men and women sleep in rows, lined up one after another for block after block in makeshift tents or on cardboard mats on the sidewalksthe mad, the afflicted, and the disabled alongside those who are merely down on their luck. Criminals prey on them, drugs such as heroin and crystal meth are easily available, sexual assault and physical violence are common, and infectious diseases like tuberculosis, hepatitis, and AIDS are constant threats.